As meat supplies grow for export demand, trade and tariff doubts hurt on-farm prices

Large supplies of meat and dairy, possibly record-setting tons, are coming to U.S. consumers.

For consumers, this can be good news with lower prices at grocery cases. For producers of beef, pork, chicken and milk it doesn’t bode so well.

In a mid-year baseline update for livestock and dairy, University of Missouri economist Scott Brown offers mixed outlooks.

U.S. consumers have shown strong demand. But farmers gearing up for rising exports grew their herds. With shifts in trade and tariff policies, uncertainties cloud markets. If exports falter, supplies will build in this country.

“It is difficult to pin down how much meat and dairy products will go to exports,” Brown says.

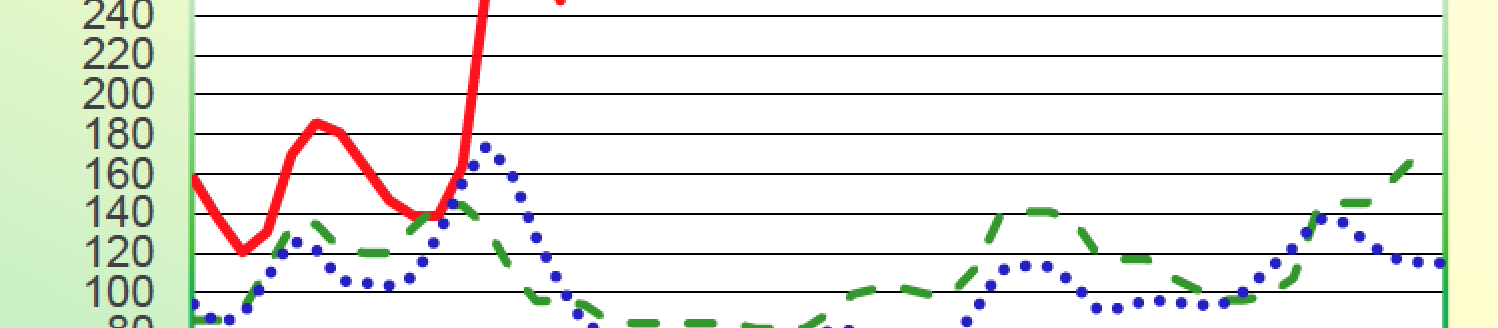

Combined per capita pounds of beef, pork, chicken and turkey will be almost 19 pounds more this year compared to 2014. That’s a 9.5 percent boost. Further, a 3.5-pound increase looms in 2019.

“Producers must hope for strong U.S. consumer demand,” Brown says. People eating more could keep products from piling up in freezers. If not, the growing supply moves through the market chain only with price cuts.

With that uncertainty, farm prices are projected to decline for fed cattle, hogs and chickens, Brown says.

“Beef export demand has grown thus far in 2018,” Brown says. For the first half of the year, those exports were up 196 million pounds above 2017. That helped offset a 480-million-pound growth.

For pork, exports grew 176 million pounds out of a 422-million-pound growth, January to June. “Weaker pork prices helped move exports,” Brown adds.

Beef cow herd expansion slowed in 2018. Drought stress on forage and water supplies helped slowing. Beef prices remain under pressure through 2020, Brown says. Demand for high-quality beef slows what could have been bigger price declines.

For hogs, increasing sow numbers with high production per sow pushed pork growth up for the last four years. Growth continues through at least 2020, Brown says.

Exports offset a large part of pork increases. That left per capita supplies at or below historical levels through last year.

Now trade doubts and production growth push domestic pork supplies next year to the highest levels since 1981.

Big supplies of beef and chicken compete with growing pork supplies. The result could be lowest the hog prices in a decade. That dollar drop can lead to financial losses for most hog producers.

Not helping pork is lack of return of the strong bacon demand in 2017.

On the poultry side, wholesale chicken prices hit records for three weeks this spring at $1.20 per pound. That had been seen only two other weeks in history. That was surprising, Brown says. Poultry production was high and chicken in storage was 10 percent above a year ago.

Chicken prices could retreat as production grows and demand returns to normal.

Turkey prices still struggle as they have for the past 18 months.

Egg demand regains footing following two years of low prices.

In the expansion mode, dairy cow numbers will likely grow in 2018 even as milk prices hit the lowest since 2009. Large herds in Texas, Kansas, Idaho and Arizona keep cow numbers largely unchanged.

Dairy exports have remained impressive, Brown says, although low prices triggered federal milk price margin protection for some dairy farms.

High production in livestock and dairy kept the consumer price index for food below 2 percent for the fourth year in 2018. The CPI runs less than the rate of inflation.

This baseline update came in conjunction with the MU Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute baseline. That covers crops and biofuels. Reports are available at fapri.missouri.edu.