Water right: College’s program creates opportunity to preserve aquifer

Open-minded, common sense individuals matched with hands-on technology are making a difference in the drive to conserve water in the Ogallala Aquifer.

Those individuals are thriving at Northwest Kansas Technical College, Goodland, Kansas, an institution that has a history of regularly raising bumper crops of entrepreneurs. The latest addition is irrigation management. In 2016, NWKTC’s Precision Ag program launched its Water Technology Farms project to promote the adoption of various irrigation management technologies to help producers in that region, said Weston McCary, director of Precision Agriculture and UAS Technologies at the college.

Students welcome the opportunity to learn how to use new techniques to preserve groundwater, McCary said, adding that is essential for agriculture and agricultural-related businesses in the High Plains.

John Gower, Phillipsburg, Kansas, grew up on a farm in eastern Phillips County near Agra. He plans to be the next generation of that operation, and as a budding entrepreneur he is bullish because he has been able to work in a program that can tap his hands-on instincts. That has included how he can incorporate technology into improving a farm’s efficiency.

Irrigation application has always intrigued him. As an eighth-grader he had the opportunity to work with Josh McClain, an irrigator based in Almena, Kansas. Gower remembers how important it was to be precise on water application.

Technology tools pay dividends, Gower said, providing ways to help producers in ways that were not possible even a few years ago.

“The biggest thing to me is the moisture probes,” he said. “There’s data to show that if you do have a moisture probe, if used to its full potential and you trust it, you will save money on pumping costs and cut down on the water usage,” said Gower, whose major is in precision agriculture with an associate’s degree in applied science. “They can now grow as much corn with less water usage. It is hard to argue against success.”

Variable rate irrigation scripts also help producers to address topography and to keep water from running down ditches, he said.

Matching those VRI scripts with a soil probe in a well-maintained pivot system can help producers to be more efficient and preserve precious groundwater, he said. Gower is also working with McClain on a precision planter and the soon-to-be graduate wants to be able to follow a passion of improving planting equipment for producers and also farming.

The High Plains economy depends heavily on the Ogallala Aquifer and both Gower and classmate Blaine Sederstrom say the key is to continue to press for greater efficiency and conservation. Sederstrom agrees that new technology is making a difference on his family’s farm.

“There has been big changes in water probes,” Sederstrom said. “When we’ve had a good rain during the summer and because it is hot and dry for several days you don’t necessarily have turn the sprinkler on.”

Sederstrom will graduate in May with an associate’s degree in applied science with a certificate in precision agriculture.

One reason Sederstrom wanted to attend nearby NWKTC was he enjoyed a hands-on style of learning. It also helps him achieve his dream of returning to the family farm about 10 miles southwest of Goodland in Sherman, County, which includes irrigated and dryland corn, wheat and soybeans. He wanted a learning experience that in turn he can use to help his family to continue to be successful.

Irrigation is crucial to the family farm. Sederstrom said his family considers themselves fortunate because they still have groundwater wells that produce 350 to 400 gallons a minute.

It is essential to gather as much data as possible, learn from it and apply the knowledge, he said. Technology allows him to break down an entire field so that it can be analyzed to find deficiencies. What might appear to be a good field can have spots that are not as productive because he has found that not every acre in a 160-acre field was created equal. Variable rate irrigation is one of the tools to help.

“Let’s not spend any extra money or putting on more water when it does not pay a return,” he said.

Another change has been a no-till operation even in the irrigated fields. In western Kansas, the heat and sun can bake the soil so keeping the ground moist and shaded helps.

NWKTC has a 300-acre field that students can work with, and Sederstrom was appreciative of McCary’s initiatives and the college’s commitment to invest in a program that will pay off in a practical way.

From a practical standpoint teaching young men and women to enter the field of irrigation technology can be important if your livelihood depends on the Ogallala Aquifer.

“We try to teach young producers that irrigation water, especially in the Ogallala region, is a finite resource and that using it moving forward will require more and more strategies to use effectively,” McCary said.

NWKTC strives to give students a hands-on experience with various technologies plus exposure to ag retailers, he said, and in that way, students can understand firsthand what options are available to them and then address problems with confidence. Being able to approach complicated topics, like water, in a confident manner is a big factor in whether practices and technologies get adopted, he said.

“We don’t teach too much hypothetical,” McCary said. “We focus on real practices, technologies and skills that get used day-to-day in ag production.”

That includes teaching self responsibility, personal conduct and an overall attitude and with “the subject of water we’ve found has a lot to do with perceptions and attitude. All the hard skills and technology build off that.”

Starting the process

Precision ag and irrigation technicians became a natural fit in 2015. While working on the curriculum development for the Precision Agriculture Technology program, McCary was approached by Shannon Kenyon of Ground Water Management District No. 4 with the idea of including at least one standalone class that focused on Irrigation Management Technology.

McCary understood the growing concern surrounding the depletion of the Ogallala as he had taught precision ag in neighboring Colorado. Concerns had emerged over a decade ago when several water right holders in eastern Colorado had their wells shut off due to declines and resulting politics.

“I felt motivated to do what we could educationally do to prepare young producers for what’s confronting them in the 21st century so that we don’t have to see more and more wells being turned off in the future.”

History plays a part

With that in mind, strategies were discussed on how to promote irrigation reduction across the region while absolutely making sure it would be economically viable for producers to do so, he said, as answers were found in volumes of research conducted by Kansas State University, Colorado State University and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. The data showed that it was not about the volume of water applied to a crop; instead it was about delivering water at key stages of plant development.

“There’s a big difference between those two concepts. Furthermore it was also about not exceeding a given field’s moisture and nutrient holding capacity and accidentally pushing valuable nutrients below the root zone due to overwatering,” McCary said. “That’s not how producers hold on to their valuable dollars, and in some areas of the United States that’s how we’ve seen surplus nitrate getting into potable water supplies and river systems.”

The research also indicated that some fields have pretty uniform soil distributions yet others have four or five different soil types, sometimes within a single quarter section, he said. By geographically mapping the soil types and then placing soil sensors in the field during the irrigation season, researchers can monitor subsurface moisture regardless of whether it appeared dry on the surface or not.

“This concept is also the backbone in principles in precision agriculture and has become a huge game changer for the ag industry,” McCary said. “We designed our Precision Agriculture Technology program and our Irrigation Management classes around some of these same ideas.”

Students have three milestone options inside the Precision Agriculture Technology program; a two-year associates of applied science, a one-semester industry Certificate A, and a one-year Certificate B, McCary said. Each student has the option to focus on a specific area of expertise in his or her second year.

“Some have focused on planters and GPS guidance systems, while others have really taken a deep dive into electromagnetic soil mapping and grid sampling. Others focus on UAS (drones), some on computers, wiring and electronics, and others yet have focused on our indoor growing lab,” he said. “Three students have left the program and gone into the industry to work with water-related technologies. In addition to our annual Ag Tech Expo where we showcase a lot of our water technology efforts, the Precision Ag program will also be offering a Master Irrigator program for producers later in the year. The program is a joint effort between Northwest Tech, Groundwater Management District 4, Kansas Water Office and Ogallala Water. The sky’s the limit for the things we can potentially teach.”

The program goes hand in hand as growers look for ways to improve their efficiency.

“Never before have we seen so many simultaneous advances and adoptions of science and technology in agriculture,” McCary said.

In the past 30 years besides the genetics and chemistry in crops, the industry is seeing semi-autonomous, Global Navigation Satellite Systems controlled tractors across the landscape using individual row controlled planters and section controlled sprayers. Growers can log into their smart device and monitor the status of 20 center pivot machines at once, while also getting infrared plant health imagery from weekly satellite passes—just sitting at the breakfast table in the morning.

Weather stations monitor exact rainfall rates at the field from 50 miles away, online fleet management platforms let a producer see where all of his or her equipment is in the field in real-time, commodities can be sold from a smartphone app, and the industry is just seeing UAS platforms emerge capable of crop dusting in swarm formation.

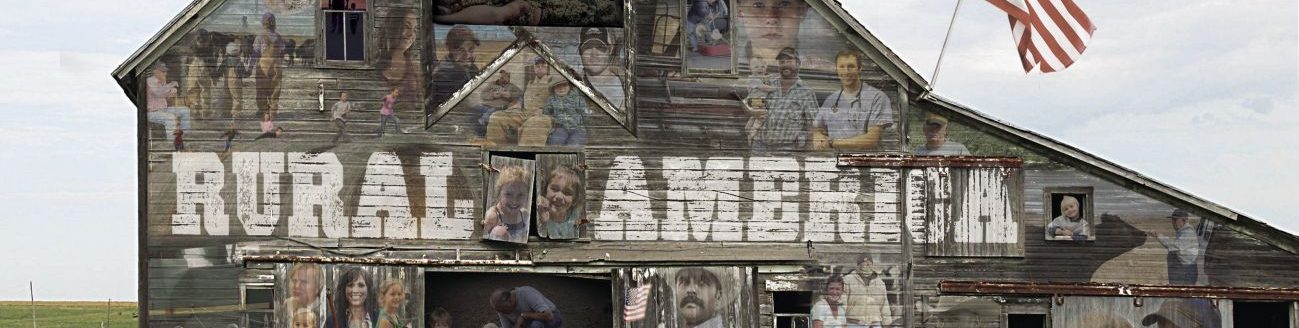

Rural innovation

All of this technology has been slowly emerging in response to a few significant factors, in his opinion. The big one is there are fewer and fewer people working in the ag sector than in previous generations, while the sector is expected to produce more volumes of product across more acres than ever before.

“We’ve been seeing a rapid decline in the ag workforce for several decades now, and that includes industries like crop dusting where the average age of a pilot is nearly 60 years old,” McCary said. “The irrigation industry is another part of the workforce that has seen substantial declines. Ag is already asking who is going to work all that ground, fix my pivot and fly those aircraft when this generation retires.”

Workforce development is the primary focus at the college, which prepares hands-on workers for numerous industries, but agriculture just might be the biggest, he said, adding it’s arguably the biggest industry in the world. Those are big shoes to fill.

The second factor driving all this innovation is that American producers are competing more directly with world markets than ever before. So many other ag economies, like Brazil and Ukraine, have been slowly growing to competitively produce the same crops with the U.S., and these countries still have the advantage of lower labor rates while still having access to the same latest technologies.

“It’s like many of these other countries have had the luxury of skipping the last 50 years of growing pains that American ag has had to go through and they’ve jumped right into the race next to us,” McCary said. “We teach our students that this is fourth quarter football and we’ve got to compete. This is no time to coast. You cannot know too much in today’s ag, and you can’t afford to get behind.”

Dave Bergmeier can be reached at 620-227-1822 or [email protected].