Without a doubt, every sector of agriculture has been upended as an effect of the global response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Livestock producers have seen reduced capacity at packing plants because of COVID-19 precautions, causing backups in the supply of animals ready for processing.

Shelter-in-place orders have dropped traffic on the nation’s roads down to a handful of essential vehicles, reducing the demand for ethanol and biodiesel made from corn and soybeans. In early April, estimates were a loss of 200 to 500 million bushels or more of United States corn that were in a holding pattern waiting for ethanol plants to return to production.

But wheat, that affordable staple food ingredient for so many, may just be in a better position than other commodities in a post-COVID-19 world. And while economists are still trying to quantify the phenomenon that they are seeing, there are some early lessons to be learned right now in the thick of it. And perhaps some bright spots for wheat farmers to look forward to as they head into harvest.

Disruptions in the chain

In the early days of stay-at-home orders we saw news reports of flour and baking ingredients flying off of shelves as consumers turned to baking while they were home. Guy Allen, senior economist for the International Grains Program at Kansas State University, explained that situation was more a result of packaging challenges at mills than of any shortage of flour.

“We heard a lot about people staying home and cooking and baking more,” Allen explained. “Well, that retail demand for flour, bread flour, is close to just about 1% of our total demand. If we double that, at 2%, it’s still not a significant figure. But, the challenge at the mills was in the packaging and delivery of flour. Most of their flour goes into the institutional or food service sector, packaged in 50-kilo bags or larger, versus the 5-pound bags in the grocery store.” U.S. flour milling is fairly highly concentrated, with about three companies representing 75% of the total capacity, give or take. They, like so many other food manufacturing and processing companies today, are designed with packaging lines to meet the larger demand by food service, restaurants, and institutions instead of the home baker.

Still, wheat’s supply chain has been significantly more stable than other ag sectors, such as the feed, livestock or ethanol sectors. Allen explained that we’ve seen a 30 to 40% drop in processing capacity for meat just based on precautions taken to keep COVID-19 at bay among plant workers and inside facilities. On the ethanol side, which is more highly mechanized and requires less labor for processing, the disruption goes back to the oil feud between Russia and OPEC last month. It was finally settled with agreed upon cuts in production, but then stay-at-home orders were put into place around the country and demand for oil plummeted. Allen said with ethanol plants temporarily shuttering there’s been a 40% drop in capacity in that sector, and that translates into more corn needing to find a home on the market.

Situation at home

Wheat isn’t entirely unscathed in all of this.

Dan O’Brien, K-State associate professor in agricultural economics, explained in a webinar in mid-April, that lower plantings of 30.7 million acres versus 31.2 million in 2019, might now be an advantage. The U.S. Department of Agriculture had pegged the season average price in April at $4.90, and K-State economists could see it reaching $5.35 per bushel. “Right now, wheat is holding up price-wise as much as anything,” O’Brien said.

With restaurant traffic down significantly and school children now learning—and eating—at home, the institutional demand for those large packages of wheat flour, or bread products, is down about 20% if not above 30%, Allen speculated.

“Everyone is changing their eating habits,” Allen said, and O’Brien echoed that comment. Americans like to dine out, whether through a fast food or white tablecloth establishment. Whereas, the rest of the world is more inclined to stay home and eat, Allen said. Still, Allen warned, the demand we lost in the last two months of stay-at-home orders in the wake of fighting COVID-19 is not likely to ever be recovered fully. Re-opened restaurants will see their seating reduced by half to two-thirds to keep enough spacing between diners to reduce the spread of germs. And, with unemployment at record highs, there probably won’t be disposable income for those diners to dine out in the first place.

Supply and use numbers are pretty tight, but our hard red winter wheat export prospects are encouraging, according to O’Brien. That could be especially true if the impact of COVID-19 in other countries disrupts their systems. O’Brien said the U.S. could find itself in a position to meet export demand down the road.

Looking ahead to demand abroad

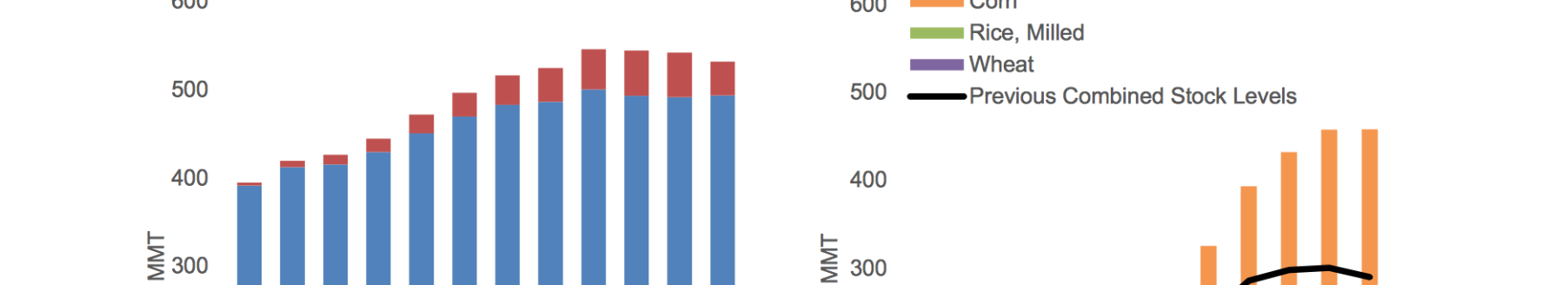

Allen, who has extensive experience in international trade said the world went into the COVID-19 pandemic with a record high carryout of 293 million metric tons of wheat, after a crop of 765 million metric tons. Wheat, he said, has one thing going for it on the global commodity complex, and that’s that it is staple of so many diets.

While there were similar carryout numbers for corn and soybeans globally, the world’s countries look at their supplies of wheat and their populations and are choosing to build their food reserves. There are now reports of countries who are large wheat suppliers to the global market turning off their wheat exports in an effort to ensure their food security at home in the wake of COVID-19.

“In the wake of COVID-19 concerns, food security is an increasing issue for some countries,” Allen said. “Exporting countries like Russia and Ukraine are shutting off exports to conserve their domestic supply to make sure that they don’t have food inflation. Russia is the largest exporter and Ukraine is right behind them, of wheat in the world.” When Russia shuts off wheat exports, that demand shifts to Europe and the United States, he said.

Additionally, on the importing side, traditional wheat importing nations are looking to increase their reserve stocks, Allen said. While that’s artificial demand to an extent, it will still see wheat moving on the market. For example, he said India, which already had large carryover stocks of wheat, is increasing its stocks to a point where it might see pushback from the World Trade Organization. China is replenishing its ending stocks, and they already hold half of the world’s stocks of grain, but the government focuses on food security for its billions of citizens. Egypt, Indonesia, Turkey, Bangladesh, all countries with large populations where food security is an issue are stepping up their purchases of wheat. Not surprisingly because wheat products are typically affordable for all citizens.

“They aren’t the cheapest buyers of wheat but they are pretty close,” Allen said. Those countries are also heavily supplied by Russia and Ukraine. Or, in the case of Indonesia, are supplied by Australia, which has suffered three years of drought and have their own tight supplies to deal with. That opens a door to the U.S. and Canadian hard red winter and hard soft winter wheats.

And while typically U.S. wheat garners a quality premium on the global market, there’s still a high carryout in the U.S. and the whole western hemisphere to move, Allen said.

“U.S. hard red winter wheat had been pricing itself into feed rations domestically, quite aggressively,” Allen said. Typically 15% of the wheat crop will go into the feed market domestically, but with the demand hits that corn has taken on the feed and fuel side, it’s likely that more corn will get fed to livestock instead of wheat. And so the bright spot for our higher quality, more premium wheat, is that it will go into food security stocks.

“The flip side of that is that the inventory will hang over the market for quite some time until it is consumed,” Allen said. That’s what’s building that nearby demand in the last couple of months of prices in Chicago and Kansas City futures, he added.

Strong dollar

“The exchange rate isn’t something we think about very often, but exporting countries think about it a lot,” Allen said. “The U.S. dollar in the last 3 years, but particularly now in the wake of COVID-19 situation, is a refuge for securities, a safe haven. And it’s very strong right now. Other countries are seeing devaluation in their currency.

“Wheat may seem very cheap in the U.S., but it is very, very expensive to importing countries,” he added.

Just last week, Brazil, which is a big purchaser of U.S. wheat and a large exporter of its soybeans, saw historic high sales of its soybeans in the Real, its currency. And yet, at the same that currency hit record lows against the U.S. dollar.

It’s just one more consideration farmers must have in their minds going into harvest.

Harvest on the horizon

The International Grains Council projects a new record production of 769 million metric tons, Allen said, and you can expect carryout to increase on the back end of that. That begs the question—do we have enough room to store a record crop?

“We have plenty of space in the U.S. for storage, but the issue will be the size of the corn and soybean crop,” Allen said. “If we have a record corn crop this year, a record soybean crop, those commodities will push for space. Anticipate board carries to remain fairly large and fairly wide too if we have to carry this commodity.”

Typically, anytime there’s an increase in global ending stocks, the U.S. carries those in a large way, Allen explained. “We have the capacity and we have the access to ready financing, and capacity to manage price risk over multiple seasons moving forward.”

Economists like Allen and O’Brien are still gathering data as to how COVID-19 influenced wheat trade this year, of course. But these are just a few trends wheat farmers can follow as they bring the crop in the coming months.

Jennifer M. Latzke can be reached at 620-227-1807 or [email protected].