Drought conditions persist in some areas of High Plains

Brian Fuchs, monitoring coordinator with the National Drought Mitigation Center, recently gave a regional update and discussed the drought situation in the central United States during a webinar hosted by the USDA Climate Hubs, National Drought Mitigation Center, NOAA and the National Integrated Drought Information System.

Fuchs gave his perspective on how the region is looking drought wise. He just finished two weeks as the lead drought monitor author, and “really dug into a lot of the data.”

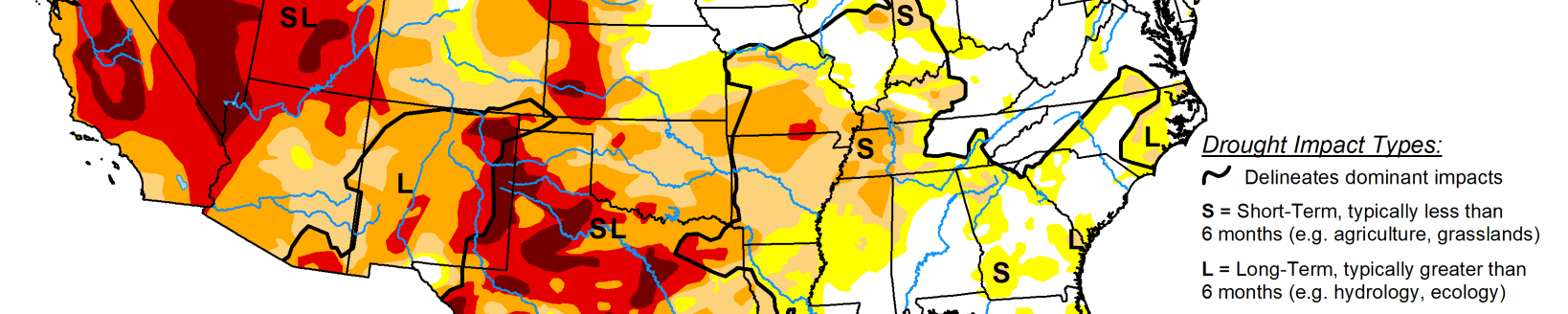

On the most current map at the time of the webinar, Fuchs said you could definitely see the differences between the eastern and western parts of the country.

“Over the east, not a lot of drought to speak of but as you get into the High Plains and central Plains and make your way into the Rocky Mountains and especially into the Southwest, we see some definite drought issues that have been developing here, especially over the last several months,” he said.

In parts of Colorado and into Wyoming, drought conditions are starting to intensify. Back at the start of the water year on Oct. 1, only 5% of this region was seeing any kind of drought.

“We had no severe extreme or exceptional drought at that point in time,” Fuchs said.

Currently, of the northern Plains region 41.26% of this region is in drought, 19.08% in severe drought or worse and a little more than 5% of the region is in extreme drought.

In the Four Corners region it’s a continuation of the same “what I would call bad news,” Fuchs said. In this area, 91.6% of this region is in drought currently compared to a year ago. It was at 3.81%, the start of the water year.

“I think it’s even more of a continuation of the same—what I would call bad news,” he said.

Most of the drought in this region was in the D2 or severe drought rating or moderate drought rating.

“We really didn’t see any of that extreme drought on the map at that point in time,” Fuchs said. “So realistically, a lot of this drought has developed quite rapidly, and even in a dry part of the country, we can still see droughts that develop in a short period of time due to the nature of the climate that we’ve been seeing which has definitely been hot and dry.”

So how did the drought conditions get to where they are? Starting a year ago, on the drought monitor in western parts of New Mexico, it was really the only place showing drought in the entire region.

“We had several areas that were being designated in the yellow or abnormally dry, but for the most part, even in parts of Colorado and Wyoming where we’re seeing a lot of drought now in and into western Nebraska we were not seeing anything a year ago at this point in time,” Fuchs said.

By the end of the calendar year 2019, the Four Corners region really started to suffer. Far western Kansas and eastern Colorado was starting to see more dryness develop. Other areas were far better off as far as precipitation levels go.

But if you look into northeast Colorado, almost all of Nebraska, almost all the Wyoming, there was no drought really to speak of, and even much of Arizona and New Mexico at that point in time,” he said. “We had some dryness developing but no widespread issues of drought that we were following.”

By the beginning of May 2020, there really wasn’t a large expanse of drought like current conditions indicate. Areas like eastern Colorado, western Kansas and into the Oklahoma and Texas panhandles and northern parts of New Mexico, were areas that by the middle part of the spring season were facing lack of rainfall, but it wasn’t yet concerning.

“Realistically yes there were some dry spots, but not really anything that was standing out as far as drought developing as we started in May of this year,” Fuchs said.

Historically in those areas from 2000 to present, there has been a lot of ongoing drought in this region throughout the entire last 20-year period.

“We go to the southern Plains, and we see quite a bit of the same pattern,” he said. “We see more peaks and valleys, meaning that drought has flared up and kind of diminished over time. But we still see those patterns, and then even in the southwest.”

You’ll be hard pressed to find areas in that same time period where “we did not have a drought,” according to Fuchs.

“We have heard a lot of scientists talking about that this hasn’t been a single year drought period or even a multi-year drought period, but really developing into a multi decadal pattern that we’ve seen drought pretty much consistently over the last 20 years,” Fuchs said. “And when you look at these three regions of the country, the southwest definitely does stand out as being the most consecutive years of drought taking place, but all of them are behaving quite similarly.”

Drought really has not subsided for any long period of time. Fuchs said there’s been ebbs and flows of better periods, but not really any diminished long-term period of drought that have been observed in other areas of the country.

“That’s something that’s really concerning, and something that we at the drought monitor and the group of authors are really paying attention to that,” Fuchs said.

Although the seasonal outlooks were outdated at the time of the webinar, new ones came out Aug. 20 for precipitation and temperature. The one that came out July 16, was for August, September and October temperature and precipitation, Fuchs said, “so far through the first three weeks of August, we’ve really hit those spot on.”

“We have seen the above normal temperatures, highlighting the area of the West, especially the southwest,” he said. “And we’ve seen this dry signal over the Intermountain West and into the Southwest. The monsoon really hasn’t developed too much this year.”

When the monthly drought outlook came out at the end of July, Fuchs and his colleagues were anticipating the expansion of the drought through the west, even starting in western Nebraska and Kansas and westward.

“The outlook at the end of July really was hitting this pretty good,” he said.

The new outlook, which came out Aug. 20, isn’t anticipating much of an expansion in drought.

“So it’s showing you how rapidly some of these conditions have been changing,” Fuchs said. “It’s going to be interesting to see on Thursday what this map looks like. I anticipate it is going to look a lot more like the monthly drought outlook that we saw at the beginning of August.”

Fuchs’ best guess is the seasonal drought outlook is going to look like these drought areas aren’t going to go away any time soon.

“They’re going to be persisting, and we’re really going to be anticipating what that winter season is going to look like, especially in the mountainous regions,” he said.

Fuchs was asked if the monsoon was going to happen in 2020, or if it was too late in the season.

“I think the full impact and effect of the monsoon season is going to be diminished for this year,” he said. “I would definitely say it’s going to be a miss.”

Some areas of New Mexico and even up into southern Colorado have benefited from some of the monsoonal moisture, but looking at areas in Arizona, southern Utah, southern Nevada, and southern California, they may not be as lucky.

“It’s definitely been a miss there,” Fuchs said. “We can pay attention to and see if that’s going to help the region at all.”

The monsoon did add some humidity to the areas, but the precipitation has been hit and miss.“I think parts of the Phoenix metro area received their first rainfall (Aug. 17), since about the middle of April,” he said.

Fuchs was going to wait and see what the Aug. 20 outlook predicts before he decides what to say about the rest of the year. He has seen information from the Climate Prediction Center saying there’s an increased likelihood of a La Nina building.

“It’s currently happening and it would peak through winter,” Fuchs said.

He questioned if that would that have an impact on precipitation patterns through the drought stricken the West through winter. One thing to really pay attention to is the El Nino and La Nina cycles and how they impact the winter season.

“It has to behave the way we would anticipate them to behave,” he said. “It seems like several of the last El Nino or La Nina events that we have had have not behaved in that traditional manner that that we align them with. So, maybe, it’s not a great answer, or very scientific, but it’s probably my best answer right now.”

Looking back at the last 20 years of temperature trends and how it correlates with the types of droughts experienced over time, Fuchs sees a pretty strong correlation.

“Now if we wanted to have something that was based on a longer period, we can look at those longer trends and see what temperatures are doing,” he said.

The team at NDMC has been working on some trend products, and depending on the time scale looked at in recent decades the southwestern United States sees some of those trends.

“But as you go into longer timescales that go from the ‘50s on, some of that signal gets diminished,” Fuchs said. “So it really depends on what periods you started looking at, and how substantial that temperature trend is. But in any event, warmer temperatures are definitely going to be contributing to drought in the West.”

Kylene Scott can be reached at 620-227-1804 or [email protected].