Grain storage on the farm remains an important but dangerous task.

To preserve quality means someone physically has to climb into bins to check, and on family farms teenagers are often tasked with the work. Some of the most serious accidents—at times fatal—occur when someone suffocates in a bin.

That stark story led Benjamin Johnson and Zane Zents, from the University of Nebraska-Omaha, to undertake development of the Grain Weevil, which is a grain extraction and bin management robot. Grain Weevil is a tool that can take the place of a human to complete tasks inside of a bin. Their project did not go unnoticed as Johnson and Zents were recipients of $10,000 as the undergraduate team winner of the Eat It! Lemelson-MIT Student Prize this past spring.

The roots of the project started as a favor to help a farmer friend, Johnson said.

In 2019 the farmer told Ben and his dad about how dirty and dangerous bins can be and yet it was important to regularly check the quality of the grain.

“Can you build me a robot so I don’t ever have to get into a grain bin again or my kids don’t have to get into a grain bin either?” Johnson said. “My dad and I started brainstorming and we eventually came up with an idea for a Grain Weevil robot about two years ago.”

Ben Johnson recently graduated with a bachelor’s in electrical engineering. He grew up in Aurora, Nebraska, and is familiar with agriculture’s importance to his community and state’s economy. The early focus of the project was on corn and soybean storage because those crops are staples in Nebraska.

“We’ve been full speed ahead and learning more about the ag industry and the needs of farmers,” Johnson said.

Zents, an Omaha native who has a bachelor’s in computer engineering, computer science and mathematics, was called upon because of his software expertise. Zents quickly understood the need for a tool. He also knew that such a tool was going to need software and a design that could withstand harsh conditions.

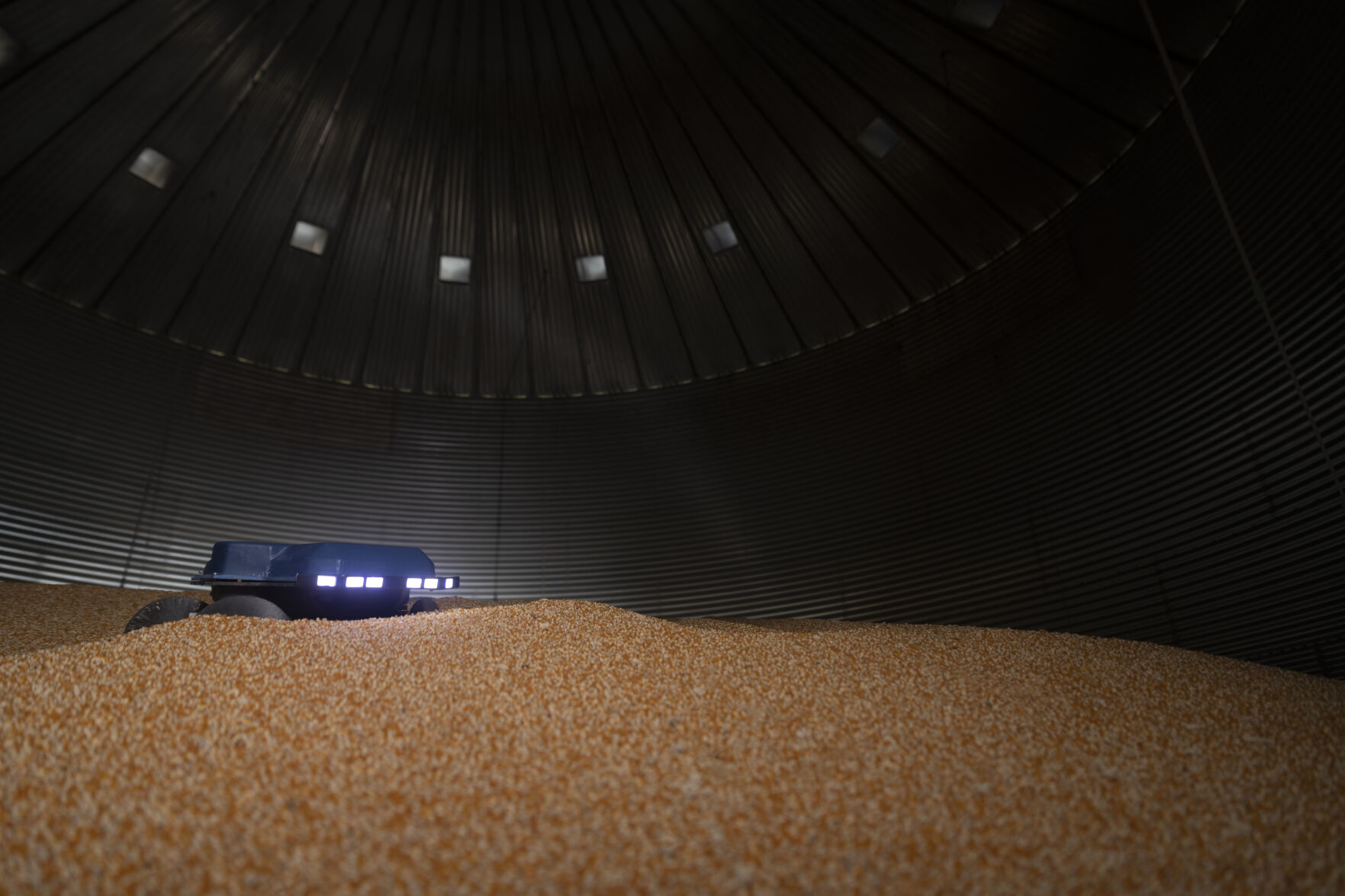

The Grain Weevil weighs less than 30 pounds, is small enough to fit in a backpack and uses horizontal augers and gravity to level and redistribute grain within a bin, according to the Grain Weevil’s website, www.grainweevil.com.

Instead of having an individual enter through the top of the bin to do all the leveling and measuring work, Zents said, he would instead open the top of the bin and drop the Grain Weevil on top of the grain pile and then from the safety of the ground use remote tools to guide the robot.

The robot rests on two augers that propel it forward and simultaneously do the work of leveling and aerating the grain by scurrying across the top surface without flipping over or getting buried, the website notes. The drilling action of the augers in conjunction with the natural force of gravity facilitates grain movement and maintains appropriate viscosity, moisture levels and temperature. The robotic device is waterproof and dustproof as well as able to dig itself out from as much as 5 feet of grain if it accidentally buried.

The robot is currently operated via remote control, but a fully autonomous self-driving vehicle is being developed. Battery life for the Grain Weevil is about three hours. A longer battery life is anticipated that will allow for a full maintenance cycle to be completed with one charge.

The promise of Grain Weevil continues to impress Zents as he remembers the starting point of the tool.

“Ben came to me with this project and told me a little bit about what it was about after talking to a few farmers and seeing the profound impact that something like this could have and that it could save lives,” Zents said.

The project could make a difference and he is excited to see it go from prototype to the marketplace where it can be an essential farm tool, he said.

The entrepreneurs both heard about grain bin accidents and many near misses from many farmers, and research bore it out too.

“Everybody we know has a story to tell,” Johnson said.

Their research indicated that farmers and their children, sometimes as young as 14, must ensure the grain is level and properly aerated. To do so they have to enter the grain bin, enduring temperatures up to 140 degrees Fahrenheit to physically move grain with shovels or other tools. They noted that United States farmers put their lives at risk by entering grain bins where they may suffer illness, injury, entrapment and even death. On average, one in five grain bin accidents involves a boy in his teens. Also, up to 7% of farmers in the U.S. develop a disease commonly known as farmer’s lung brought on by allergic reaction to grain dust that causes lung inflammation, shortness of breath, increased heart rate, cough and sometimes permanent lung damage. Farmers typically live just eight years after diagnosis.

“We are passionate about getting the farmers out of the bins,” Johnson said.

It also has dual purpose of helping farmers maintain benchmarks for quality, the two men said.

When released, the Grain Weevil will be able to be used by not only corn and soybean farmers but also those who harvest wheat, sorghum, oats and other small grains. Trials with farmers are set to continue throughout the fall.

The target date for getting it to the hands of producers can be determined once all the field trials are completed and Johnson and Zents are satisfied with the many aspects of quality control they insist upon.

The tool has to be dust and moisture resistant, and fall field trials will also subject the Grain Weevil to harsh conditions, Zents said. They are also moving through the patent process.

Zents said the Grain Weevil is expected to be sold for over $3,000 and equates to about $0.075 per bushel. Grain dust is not only tough on humans but also on computers, and Johnson said they are looking at ways to provide service contracts so the Grain Weevil will have the capability to last five years.

“We want farmers to have maximum benefit,” Johnson said.

For more information, visit www.grainweevil.com.

Dave Bergmeier can be reached at 620-227-1822 or [email protected].