The 75th annual National Barrow Show has come to an end in Austin, Minnesota. Like all livestock events, this hog show has undergone the same evolution of change necessary to meet the needs of the people participating.

Even though I obviously did not attend the first one in 1946, one component present in that event remains in 2021: the people. The hogs come and go and, trust me, through this set of barns tons of hogs have walked but this event always has and always will hold a tremendous amount of history and tradition regarding what built the United States food production system.

For me personally, this has always been a tremendous event. In 1986, as a 19-year-old kid, I hit a home run with my first national level win showing a Spot boar, Dozer, that was named reserve champion. I will never forget getting in the pickup to head home with my friends and Robert Symonds, a long time Spot breeder. He said, “Kid, I have been exhibiting at the NBS for 50 years and never pulled off what you just did here.” While I remember some things about that boar, I clearly remember how people treated me after the win. And I was thrilled with the fact that Farrer Stock Farm in Indiana chose to purchase that boar for $3,600.

In 2021, I was fortunate to be on the giving end of a memory that will live forever. As a board member of the Team Purebred junior swine association, I was honored to present the first-ever Team Purebred Legend Award for Youth Development to Ernie Barnes. Within the entire pork industry and particularly in the world of purebred pigs and youth development, Barnes is truly a leader. As we gather in Austin every year with fewer hogs on display than years past, we all recognize that the hogs are just the excuse to gather and celebrate the community of farming.

I found it interesting to take a look at a snapshot of what life was like in 1946. The federal minimum wage was $0.40, the average annual income was $2,600, a new car cost $1,125, one year’s tuition at Harvard was $420, a porterhouse steak was $0.59 a pound, and a can of Spam (invented in Austin) cost only $0.30.

Interestingly, history tells us that World War II had been completed for over a year already by fall 1946 but the food rationing and effects of the war were still being felt. I can only imagine this would have been a time of great optimism about the future demand for all things. Hormel Foods, which created Spam in 1937, actually also owns the brand name of The National Barrow Show. Hog buyers from everywhere throughout the land would migrate to Austin to seek the next year’s supply of “good quality” market hogs. Keep in mind that the quality aspect in this day would have been totally driven by the “beauty in the eye of the beholder” and not carcass data.

One thing I find quite interesting is the history of Spam itself; truly it has stood the test of time, despite a major file of hate letters from American GIs on the front lines of World War II. George H. Hormel, a World War I veteran, actually spearheaded the development of Spam as a cost effective, easily preserved protein food product. Containing only six ingredients, Spam was not designed for the war effort but certainly exploded in growth as a result of it. Some theorize, but have not documented, that Spam actually stood for shoulder, pork and ham.

The war ended and Hormel needed to find another way to really push forward without the demand for Spam by the federal government. Clearly one of those endeavors was the first National Barrow Show in Austin. The goal was really not any different than what is accomplished today and that is to gather folks and seek a network of people from every corner of the country to find progress. Today, many would argue that the purpose of youth livestock events has everything to do with the youth and little to do with the livestock. At the end of the day, it is still about networking with people because together we can accomplish anything we can dream up while sitting in a circle and solving world problems.

Circling back to Barnes, he is the ultimate networker in so many aspects of the community of livestock production. It was quite simply an honor to recognize someone who has quietly accomplished so much for so many without them really having any awareness of his carrying the water. Far too many times we do not recognize special individuals and their contributions until it is too late and we need to do better at that. Fortunately, in the case of Barnes, our timing was perfect.

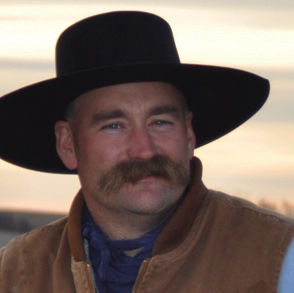

Editor’s note: Trent Loos is a sixth generation United States farmer, host of the daily radio show, Loos Tales, and founder of Faces of Agriculture, a non-profit organization putting the human element back into the production of food. Get more information at www.LoosTales.com, or email Trent at [email protected].