As high grain prices meet high temperatures, clock is ticking for corn, soybean growers

After years of depressed commodity prices, this could be the year for Arkansas grain growers to cash in—if just a few things go their way.

The price of corn hit a nine-year high in April, as growers in South America experienced a low yields and grain exports from Russia and Ukraine have been significantly reduced by war and global sanctions. Even in the United States, much of the so-called corn belt experienced drought or near-drought conditions throughout the planting season, delaying progress as summer approached.

Even as grain futures dropped overnight June 22 over concerns of a potential global recession, November soybean futures still topped $14.39 a bushel, and corn December futures sat at $6.75 a bushel.

Arkansas grain growers encountered wet conditions in the spring, which also led to slow planting progress, but eventually found their way to a successful planting season overall. Jeremy Ross, extension soybean agronomist for the University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture, said this year’s fight isn’t over yet, however.

“The other big thing, especially with this pattern we’re in right now is that we’re looking at temperatures of 95 degrees or higher for the next 15 days. There’s not a drop of rain in the forecast.

“If this is a pattern we’re going to see for the rest of the summer, yields are probably going to be impacted quite a bit,” he said.

Topsoil moisture is low throughout much of the state, with about two-thirds of the state registering levels at or below 30%, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s June 21 Arkansas Crop Progress and Condition report. Ross said growers have begun to explore pushing the boundaries of agronomic recommendations.

“We’re just trying to finish what we’re trying to plant, but we’ve got zero soil moisture,” Ross said. “Some farmers are trying to find moisture by planting a little deeper than I recommend. That can cause some problems.

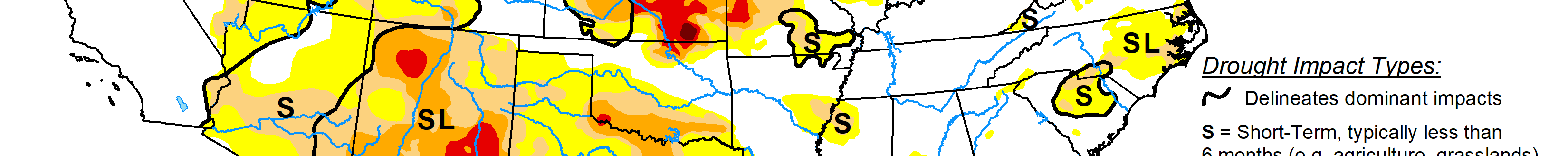

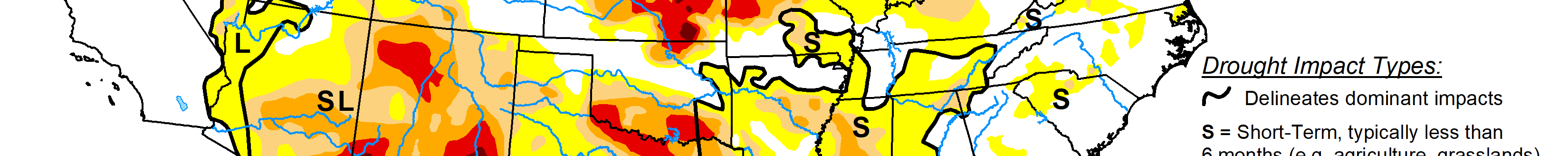

According to the most recent drought map from the U.S. Drought Monitor, released June 23, the only county in Arkansas in “abnormally dry” conditions was Fulton County. Small portions of seven other Arkansas counties were also shown to be abnormally dry; the vast majority of the state was shown to be outside of drought condition.

About a third of the United States, however—everything southwest of a line running from east Texas to southern Oregon—appeared to be in severe, extreme or exceptional drought.

The U.S. Drought Monitor is a function of the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Ross said he has fielded a number of calls from Arkansas growers interested in irrigating “small beans”—newly emerged soybeans that haven’t yet sprouted leaves. Ross said that while the research doesn’t find a lot of efficacy in irrigating soybeans so early in their growth cycle, it may be the best option for some.

“I’m not a big fan of that, but I’d rather irrigate small beans to give them some moisture versus just watching them die,” he said.

Arkansas corn

Likewise, Arkansas corn may have an excellent 2022, despite high input prices on a notoriously high-input commodity.

“Grain prices—if you’ve got grain to sell—are great,” said Jason Kelley, extension wheat and feed grains agronomist for the Division of Agriculture.

“During planting, even though the price was good, some farmers were deterred by the fertilizer prices,” he said. Overall, fertilizer prices in the United States have doubled and even tripled over the past year.

“The ones who have corn are pretty excited,” Kelley said. “Those that can grow 200 bushel corn at $7 a bushel, well, that’s a lot of money, assuming it didn’t cost them $1,400 an acre to put the crop in the ground.”

One of Arkansas corn growers’ chief advantages over many other corn-growing states is irrigation. Ross said that other than Nebraska, which typically irrigates its corn crops, other states throughout the Midwest rely almost entirely on rainfall.

While corn growers may be all smiles, producers who depend on grain to feed cattle and other livestock operations may not be in such high spirits.

Cattle outlook

James Mitchell, assistant professor of livestock marketing and management for the Division of Agriculture, said that the high grain prices may force cattle producers to cull more deeply into their herds than they’d prefer if forages aren’t top-notch this year.

“Arkansas is a cow-calf state, so higher corn prices will generally affect all of our commodity feeds,” Mitchell said. “If we don’t have a good hay season this summer, our only substitute is to feed grain—and if grain is this expensive, then we’ve got a compounding problem. That could lead to some hard decisions this winter.

“I’d encourage cattle producers to start thinking about what they need from their hay crop this summer to get through the winter, then start budgeting out how much, if any, feed they’ll need to buy to offset that, etc.,” he said.