The topic of soil moisture is not a new thing to Michael Cosh. He grew up on a dairy farm in northern New Jersey and understood at an early age that knowing the amount of surface soil moisture was useful when trying to prevent his truck from being stuck in the mud. But he soon learned that fickle soil moisture could tip the proverbial scales for farms that grapple with higher crop insurance and drought conditions.

Today Cosh is a research hydrologist for the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service, and he is leading the agency to inform farmers and engineers about the side effects of soil moisture so that farms have a chance to thrive under agricultural challenges.

"There can be severe financial consequences for farmers if there is too much or too little soil moisture," Cosh said. "This means farmers cannot easily manage their crops due to ‘prevented planting.’ Prevented planting occurs when tractors cannot traverse fields to plant because the soil is too wet. When this happens, the farmer loses money and wastes resources. Likewise, a ‘delayed harvest’ occurs when harvesters cannot harvest crops at the end of the season due to soil moisture or drought. Both scenarios have severe financial impacts on farmers, the agriculture industry, and the food on our dinner tables."

A part of the severe financial impact includes higher crop insurance and the high cost of water for irrigation. Since 2008, the USDA’s Livestock Forage Disaster Program has offered over $7.6 Billion in assistance to farmers to offset this cost. But monitoring soil moisture can provide farmers with over 70 percent cost savings on irrigation. These challenges are some of the reasons why Dr. Cosh pulled together a research team of colleagues from federal agencies and higher education.

The research is conducted jointly with teams from the National Coordinated Soil Moisture Monitoring Network, the Marena Oklahoma In Situ Sensor Testbed, and the annual National Soil Moisture Workshop. The shared data are compiled from in-ground and satellite sensors that have been placed in the ground across multiple states. Station data collected by several national and state networks provide information to the National Mesonet Program at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

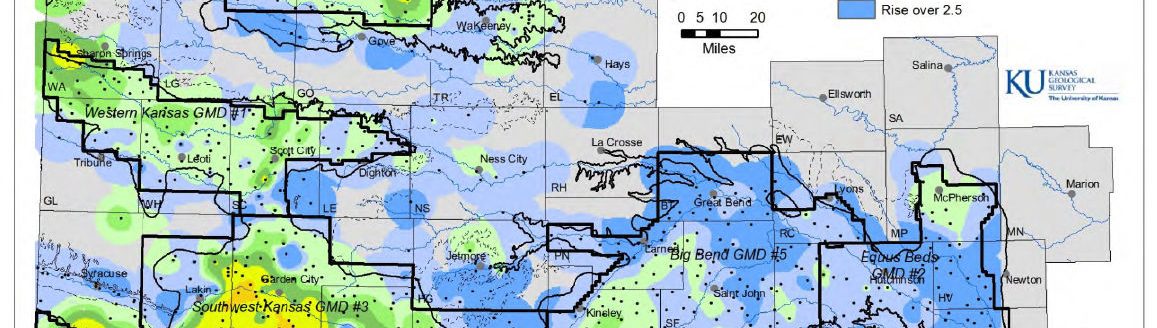

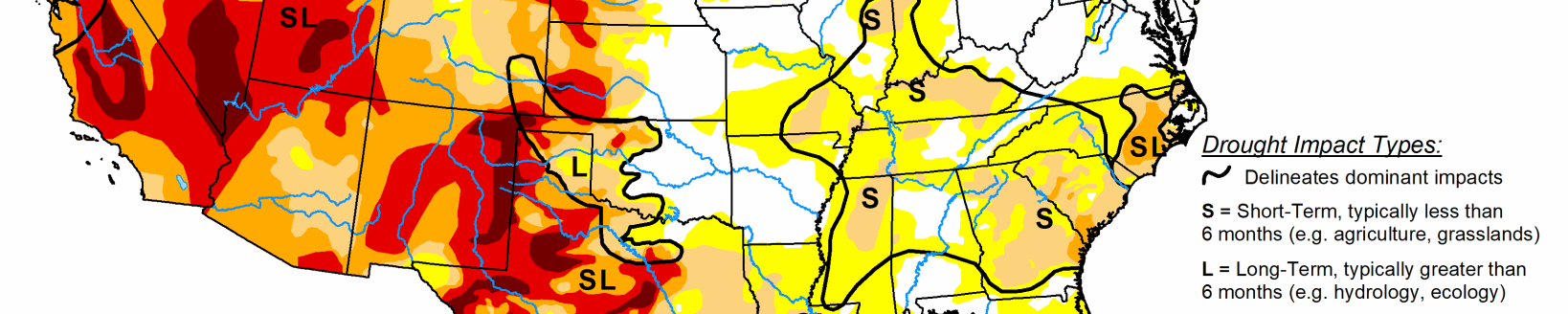

The sensors accurately rate the soil’s moisture so that USDA and NOAA can determine and monitor the drought status. These data also inform water managers in basins with significant irrigation and water usage. Some farmers directly access data from the USDA’s Soil Climate Analysis Network or NOAA’s Climate Reference Network.

Individual farmers rely upon the government’s decisions regarding the drought monitor to be accurate and in-ground monitoring is the key to that. Once the committees translate the data, farmers can prepare their soil for a pending drought, improve crop insurance decision-making, gauge the probability of flood and flood damage, and monitor the impact of climate change.

Additionally, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is expanding soil moisture monitoring in the Upper Missouri River Basin by adding over 300 stations to the national footprint. These stations will help Midwestern and Western states, as well as local farms, to monitor their soil moisture and improve flood prediction and crop yield forecasting.

"We’re interacting with network operators regularly to develop end-user listening sessions and soil moisture standards," Cosh said. "River forecast centers and state climatologists are some of the primary users of soil moisture information at the regional level. The findings ultimately help certain parts of the country to better manage their water resources."

Cosh is a leader in many of these networks, steering the teams toward successful resolutions in some of the nation’s most hard-hit agricultural areas.

In addition to national soil moisture networks, there are ongoing region-focused efforts designed to solve national agricultural challenges. A consortium of state soil researchers in Florida, Georgia, and Alabama are continually increasing their monitoring programs to better capture soil moisture status across their regions. They are also exploring ways to better increase the quantity and quality of soil moisture stations in the southeast so they can capture the changing dynamics of soil moisture distribution.

The Agricultural Research Service is the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s chief scientific in-house research agency. Daily, ARS focuses on solutions to agricultural problems affecting America. Each dollar invested in U.S. agricultural research results in $20 of economic impact.