After decades of basic research that led to successful scientific innovations, Randall Prather and his team of investigators at the National Swine Resource and Research Center at the University of Missouri have become the go-to source for genetically modified pigs used by researchers across the United States to study various diseases that impact humans.

Keeping up with the ever-growing demand amidst limited resources has become a challenge—until now.

MU has earned $8 million from the National Institutes of Health to expand the research facility on MU’s campus and speed up the scientific discoveries that can help treat humans who are suffering from the same diseases shown in the genetically modified pigs.

“We undertake projects for things that have failed in studies with mice but are much better suited for pigs,” said Prather, a Curators’ Distinguished Professor in the MU College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources. “For example, you can’t take a mouse’s heart and transplant it into a human, it’s not going to work, but pigs are far more genetically and physiologically similar to a human, so they are very good biomedical models to study diseases that impact humans. The cardiovascular systems are very similar between pigs and humans, and baby pigs are also great for studying infant nutrition, as their nutritional requirements and the way they absorb nutrients is very similar to humans.”

Prather’s research is an example of translational medicine, as therapies and treatments that are successful in pigs may be successful in treating humans with the same diseases.

“We have pigs that go blind due to retinitis pigmentosa,” Prather said. “By collaborating with the Swine Somatic Cell Genome Editing Center here at MU, if we can develop therapies or treatments that successfully treat our pigs, that knowledge can help humans that suffer from blindness due to retinitis pigmentosa.”

In total, the NSRRC has made more than 90 different genetic modifications in pigs to study different diseases, including spinal muscular atrophy and cystic fibrosis, the most common genetic mutation affecting Caucasian adolescents in North America.

“It is very intellectually stimulating because every few months, we basically get a mini master’s degree in various fields of physiology, and this grant will help us continue this important work,” Prather said. “At heart, I’m a pig reproductive physiologist and I understand early embryo development, and with that basic understanding, we can now make genetic modifications to investigate and address all kinds of diseases.”

The NSRRC has received funding from the NIH for 20 years, and Prather has been at MU for 33 years. With requests for genetically modified pigs constantly coming in from researchers at universities all over the country, including University of California-Los Angeles, Harvard, Duke, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Louisiana State University, the University of Iowa, and the University of Indiana, the current facility has maxed out its capacity.

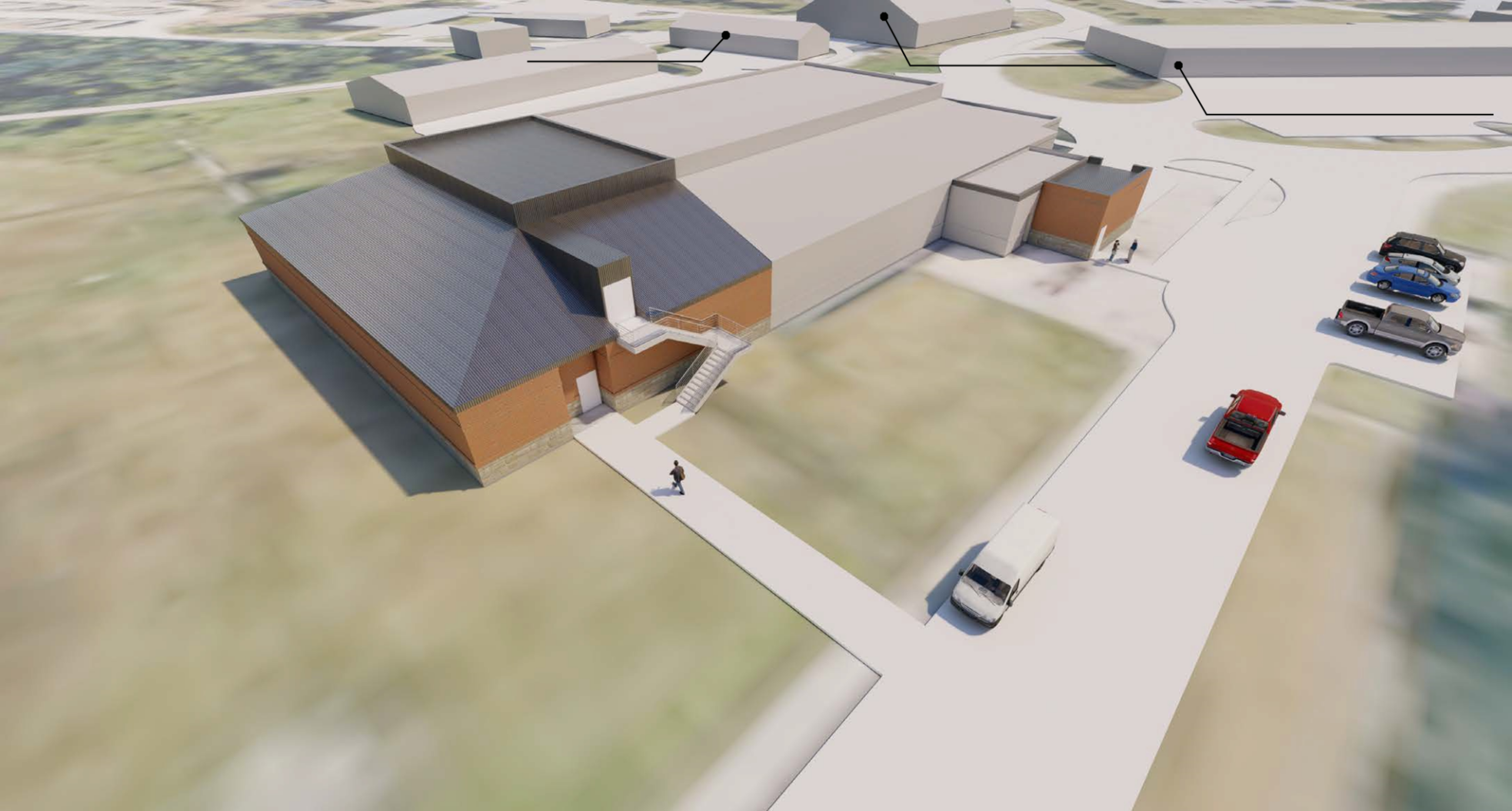

Construction on the expanded facility, which will have extremely high biosecurity protocols to ensure, for example, safe transfer of organs from pigs to humans and nonhuman primates, is expected to begin in February 2024 and be completed by summer 2025.

While the NSRRC is mainly focused on biomedical research, Prather’s research also has agricultural applications, such as making pigs that are resistant to certain diseases, which has implications for both agriculture and human medicine.

“One example is the only genetically modified pig that has been approved for human consumption, designed for people who suffer from red meat allergy,” Prather said. “We discovered that by knocking out, or disrupting, a gene that produces a specific sugar molecule on the surface of cells within pigs, humans with red meat allergy can eat the genetically modified pork, which is offered on a limited basis in a slaughterhouse in Iowa, without suffering from any digestive issues.”

Prather invented the patent for this technology that is now owned by MU. In January 2022, surgeons in Maryland successfully transplanted a pig heart into a human patient for the first time ever. Prather’s decades worth of research, work with genetically modified pigs and knowledge of pig-to-human organ transplants helped contribute to the historic accomplishment.

“Our goal is to provide resources and knowledge so that others can be successful in helping people,” Prather said. “Our work is a part of medical solutions for people and this expanded facility is crucial because pigs have so much potential for solving real-world problems. We are just one step in the journey, and it is satisfying to be a part of it.”