America’s honey bee population faces enormous stress. During 2022, nearly half the nation’s managed colonies were lost. A central threat is the Varroa mite, a parasite whose spread of viruses regularly triggers catastrophic colony loss.

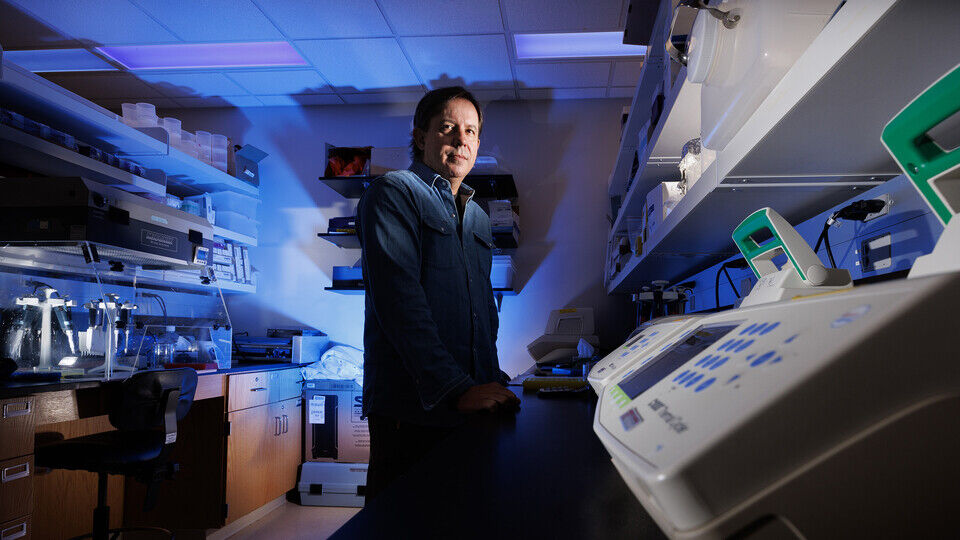

However, new research findings by a group of scientists, including Husker entomologist Troy Anderson, could provide a breakthrough in combatting the threat.

Through field study and cutting-edge biochemical analysis, the researchers have identified a specific drug treatment that stimulates honey bees’ immune systems and dramatically strengthens protection against mite-facilitated viral assault.

Infected honey bees that received the treatment, Anderson and his colleagues reported, “had similar survival rates as uninfected bees.” Once colonies received treatment at the proper level via the drug pinacidil, their viral infection rates were reduced “to levels comparable to non-inoculated colonies.”

The team, led by researchers at Louisiana State University, explained its findings in an article recently published in Virology Journal.

“We’ve provided a critical proof of concept that you can find a therapeutic target to inhibit virus-mediated mortality in bees at the field level,” said Anderson, professor of entomology at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. “That is not only groundbreaking. It’s a huge step forward in being able to improve bee colony health with specific chemistries.”

With these research findings in hand, Anderson said the task now is to develop “novel therapeutics”—drug treatments—for commercial hives. This initial treatment approach identified by the researchers might be feasible for only some beekeepers, “but what we’ve shown is that we can regulate the immune system to provide some protection for bees against viruses,” he said. “So now we need to work on other drug treatments that may work better or are more cost-effective.”

To achieve the breakthrough, the scientists needed to understand the specifics of using pinacidil to administer the proper amount of reactive oxygen species—unstable molecules commonly known as free radicals—that can stimulate a body’s immune response. The reactive oxygen species, or ROS, produced the desired immune system activity by entering cells through potassium ion channels—biological entry points whose signaling regulates a wide range of cell activity.

The researchers needed to get the ROS level just right, Anderson said, because a level of free radicals too high can damage tissues, and a level too low fails to stimulate the immune system.

“A moderate increase in these ROS can benefit bees by enhancing their immune function, which is what we’ve done here with pinacidil treatments,” Anderson said.

The scientists delivered the drug through sugar water drizzled on beehive frames. Bees ingested the liquid and passed it on to younger bees.

Previous laboratory research by the scientists had indicated the likely viability of the treatment approach, and this new project confirmed the effectiveness in the field, using hives at Louisiana State University. The hives were sizable, with at least 80,000 honey bees per hive.

Over the past 12 years, the annual loss of colonies nationwide averaged 39.6%. In 2022, the figure stood at 48%, the second-highest mortality rate on record. Bee colony loss undercuts environmental sustainability and the U.S. agriculture sector, given the broad importance of honey bee pollination for many plants and crops.

Honey bee colonies “are complex, dynamic machines,” Anderson said, and affected by multiple stressors including parasites, pathogens, pesticides, landscape and climate change. By identifying treatment to address the Varroa mite and its viral-spreading capacity, this research addresses one of the gravest threats to bee colony health.