Farmer Gratitude Summit kicks off first year, welcomes Mike Rowe

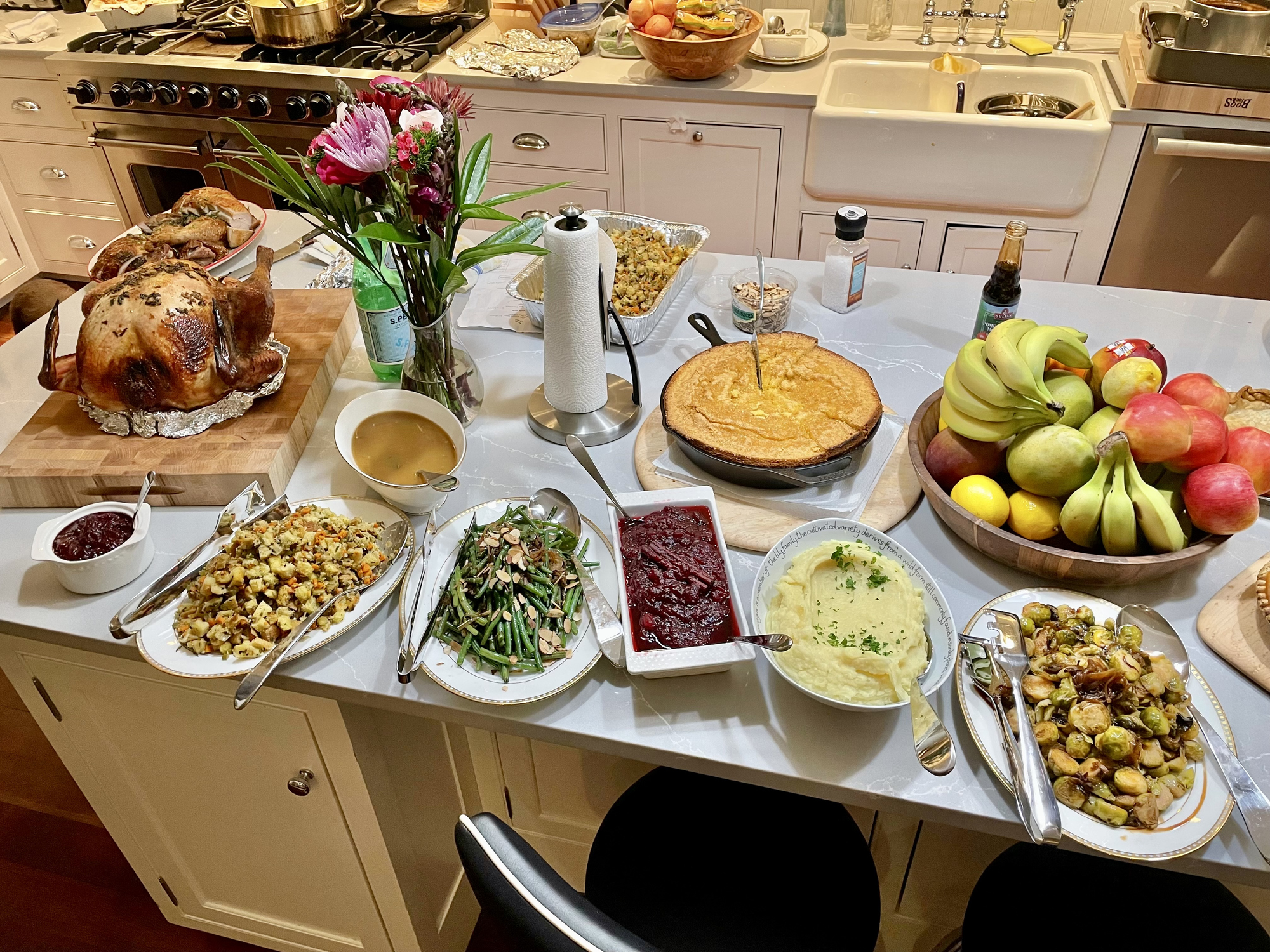

Graham Meriwether welcomed attendees to the virtual Farmer Gratitude Summit and celebrated the food on the Thanksgiving table and those who produced it. Over the course of the three-day event, 22 speakers covered subjects in nine different areas.

In one of the two Elevating Farmers segments, Meriwether welcomed Joel Salatin of Polyface Farms and television personality Mike Rowe.

Nearly 330 million Americans came together to share food with friends and family on Thanksgiving, and it’s become Meriwether’s mission to make sure people also reflect upon the food that’s actually on the table and how it got there.

“The whole purpose of the Farmer Gratitude Summit is to say thank you to our farmers and to listen to them,” he said.

Salatin, a farmer from Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, surrounds himself with a team of young people who love farming just as much as he does.

“We hear so much that young people aren’t interested in this. They’re not interested in working hard. They’re not interested in getting dirty. They’re not interested in this kind of visceral, participatory vocation,” Salatin said.

For Rowe, the what he’s grateful for question is a huge one. He grew up on a tiny farm near Baltimore County and through 350 “Dirty Jobs” shows, he reconnected to where his food and consequently his energy comes from. Rowe has worked over the years with various organizations like FFA and the Boy Scouts.

“With so many other great youth groups that form that connective tissue that I reckon is still a critical part of what’s holding our country together,” Rowe said. “So to have a seat at the table, where you can make some noise and maybe get somebody’s attention.”

Rowe said it’s hard to get the word out about certain subjects. He’s thrown his hat into the ring and strives to shine light on where it’s infrequently shown—those who produce the food.

“The one and a half percent of the people in this country who feed the rest of us three times a day. It’s a miracle,” Rowe said.

Rowe’s “Dirty Jobs” show has allowed him to spotlight those doing the producing.

“It’s such a telling point,” he said. “Because so many people are so disconnected from what really happens in modern agriculture today, and Dirty Jobs gave me a chance to shine a light on it in a in a different way.”

Salatin said farmers have been socially marginalized for a long time, and recalled when he was a soon-to-be high school graduate and a counselor proclaimed he’d be wasting his intelligence opting out of college and being a farmer.

“I’ve heard that same story from other young people who were smart and bright, and the word got out that’s what they wanted to do, and it’s socially unacceptable,” he said. “It just shows the level of—kind of denigration and condescension within the society of where we are.”

Rowe recalled meeting a miner who pulled him aside when filming in 2010 and the pair got to talking about jobs, careers, industries, etc. He told him there was only two industries in the world.

“There’s mining and there’s agriculture. Everything in your room right now was pulled out of the earth and fashioned into something useful, or grown into something we could eat,” Rowe said. “That’s it. Everything else is just jobs. Right?”

People have grown accustomed to things working and them being there. The background assumptions that the food will always be on the grocery store shelves or there will always be milk in the cooler because it just gets there by the chain of custody that brings it to you.

Kylene Scott can be reached at 620-227-1804 or [email protected].

Summit speakers tout the goodness that occurs on the farm, too

By Kylene Scott

Miners and farmers are on the front lines and everything else in some way, shape or form just trickles out from those vocations, was something Mike Rowe believes.

“You can’t eat Bitcoin, all these other things. They live in their own vertical,” said the television personality known for his show Dirty Jobs and he spoke at the recent Farmer Gratitude Summit. “And it’s ironic that they’re all subordinate to the stuff we’re talking about right now.”

Rowe has realized people have become accustomed to being able to flick on the light switch and the lights come on. They’re no longer “blown away by the miracle of flushing their toilet and watching the crap actually go away.”

“They just were no longer impressed,” Rowe said. “And since gratitude is sort of the overarching banner of this thing, it might be worth riffing on the erosion of gratitude.”

How do people lose gratitude and become so disconnected? Have farmers and ranchers become so efficient or effective in their production methods?

“Are you so good at feeding 330 million people plus three times a day that that attitude is about to fester,” Rowe said.

For Joel Salatin, of Polyface Farms, commonality breeds an assumption of expectation.

“It’s here and I don’t have to do anything and I don’t have to connect to it,” he said. “So that which we don’t participate in, we obviously become ignorant now because we’re not participating in it.”

To wrap up the conversation Graham Meriwether asked the pair about what can be done to change the course of social interactions with farmers. For Salatin, he goes back to recognizing what’s on the plate and all those who brought it to the table, when speaking with non-farmers.

“And the question is, are you intentional enough to actually have to actually fund and think and envision that the food that you’re eating is it making the landscape for the farmer that you want your grandchildren to inherit?” he said. “That’s true intentionality.”

Rowe said most people are capable of becoming disconnected from important things, and at some point in our lives we realize what’s happened.

“Addiction is an interesting theme for me because I talk a lot about people who share my addiction—smooth roads, affordable electricity, indoor plumbing, three square meals and abundant food on the shelves,” he said. “You know, those are great luxuries and hallmarks of polite society and civilization, but they’re also the fruits of my addiction.”

He’s addicted to all the good things in life, but gratitude is also a muscle and you can get “addicted to that too if you want to work on it,” he said.

“It’s a deliberate decision. I mean, most people have it in their heads,” Rowe said. “You see a veteran in the in the airport, you nod. You say thanks. Maybe pick up their check anonymously. Applying that to a farmer is not a stretch.”

Rowe suggested thinking of farmers like first responders, and it’s not hard to do.

“Being grateful just starts with being present,” Rowe said.

Kylene Scott can be reached at 620-227-1804 or [email protected].