For most of my journalism career, which started in the 1980s, I’ve heard people expressing concerns about the Ogallala Aquifer running dry. After all, it was being tapped by more and more farmers who purchased huge center pivots for irrigating thirsty crops and municipalities which were attracting larger populations across the Great Plains—regardless of water availability.

It still seemed like an improbable scenario back then, given that the Ogallala Aquifer spans across 175,000 square miles in eight states—an underground lake the size of Lake Huron. But gradually, farmers, researchers and conservation groups started to take more notice about the possibility of depleting some parts of the aquifer. That was especially the case in 2023, as drought struck across many parts of the Plains.

Now, a new Nebraska-led study aims to shed more light on the economic impact of potential groundwater depletion and perhaps change the narrative surrounding the debate. First published in the journal Nature Water, it was led by Taro Mieno, assistant professor at the University of Nebraska and his colleague Nick Brozović, professor of agricultural economics at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Brozović is also the director of policy at the Daugherty Water for Food Global Institute. Both had previously run simulations about how the aquifer responds to dry conditions.

In this study, they analyzed three decades of data on groundwater levels, weather and yield from the High Plains Aquifer to address what they learned was a primary concern of farmers: well yield, or the groundwater growers can expect to continuously draw to combat drought conditions.

“Farmers fortunate enough to be growing corn and soybean above the most saturated swaths of the High Plains Aquifer—roughly 220 to 700 feet thick—continued to enjoy high irrigated yields even in times of extreme water deficits,” the team noted in a release. But in the least saturated areas—between 30 and 100 feet—irrigated yields begin trending downward when water deficits reached just 400 millimeters, a common occurrence in Nebraska and other Midwestern states, they noted.

When the deficit approached or exceeded 700 millimeters, irrigated fields above the thickest groundwater yielded markedly more corn than those sitting above the thinnest groundwater. During extreme drought or a 950-millimeter water deficit, fields atop the least saturated stretches of aquifer yielded roughly 19.5 fewer bushels per acre, the researchers noted.

“As a consequence, your resilience to climate decreases rapidly,” Mieno said in a release. “So, when you’re operating on an aquifer that is very thick right now, you’re relatively safe. But you want to manage it in a way that you don’t go past that threshold, because from there, it’s all downhill.

Brozović said, “That has an economic consequence and a resilience consequence,” Brozović added.

Fortunately for Nebraska, the Cornhusker state covers about 70% of the water in the High Plains Aquifer. Brozović said that, in many places, it’s over 1,000 feet thick.

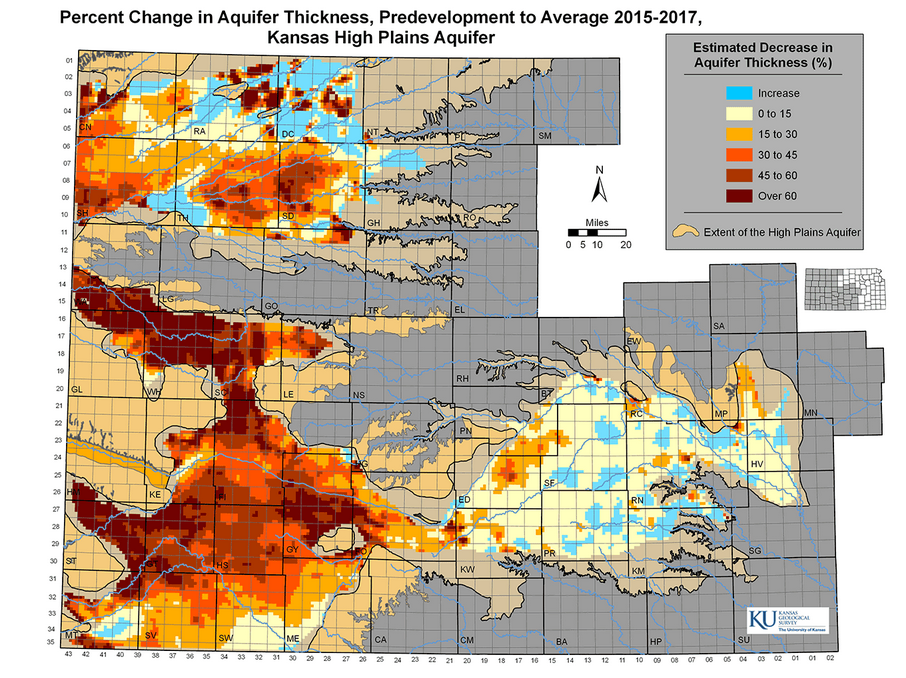

“Much of that is driven by the Sandhills with very high recharge rates and the large rivers crossing the state,” he added. But that’s not the case in many other states, especially where you are seeing this “progressively escalating impact in parts of western Kansas.”

The ability to recharge groundwater is limited in many areas because parts of the aquifer are lined with caliche, a form of rock that prevents moisture from seeping in. But Brozović said there are some exciting things that have been done on groundwater recharge, including running floodwaters up surface water canals for winter recharge.

“By operating the existing infrastructure in a new way, you get multiple benefits: Reducing the flood peak and filling up the canals when they would normally be empty, and that water slowly percolates down and recharges groundwater.”

Brozović said this research is another piece of evidence for protecting the aquifer long before it goes dry. But “there’s also this extra value of maintaining the thickness of the aquifer.” He hopes that by understanding the thickness and hydrology of the system in a more detailed way, it will be helpful in also reframing the policy debate and how the value of groundwater is portrayed.

“Typically, we see an emphasis reducing aquifer depletion rather than let’s maintain the thickness. That’s the thing that lets us maintain high levels of crop production through droughts.

“If we want to feed the world with high-quality, nutritious food and a stable food supply, we need to irrigate,” he noted.

Editor’s note: Sara Wyant is publisher of Agri-Pulse Communications, Inc., www.Agri-Pulse.com.