January—for me and my travels—has been very rewarding for a couple of reasons but mostly because I really returned to my roots. In 1979, I purchased my first purebred Spotted bred gilts and the bug of studying genetics has always interested me.

I started January at the Pennsylvania Farm Show and then spent nine days at the National Western Stock Show in Denver with a trip to the South Florida Fair during that time. Recently I attended our neighbor’s, Jerry and Gary Dethlefs, Angus bull sale. Those livestock encounters caused me to stop for a moment and think about the individuals who have continued to truly be genetic breeders of livestock.

I realize this is going to sound very elementary, but genetics are the key to the future of food. Genetics have always been the key and today we have so many more tools to truly discover the needed genetic components for an improved food system. I must admit that it was a conversation at the first event in PA that caused me to think harder about what is happening right under our nose and we don’t seem to be smelling it at all.

I am not ignorant to the fact that consolidation has always been a part of life in every single business but in the livestock business the number of genetic companies that are now owned by global interests is troubling to me. Genetic progress will be limited when breeding decisions are being made in board rooms instead of across the kitchen table.

Clearly my interest is in livestock, but I just read an interesting piece about the preservation of more than 1 million varieties of plant seeds that are being stored in a frozen vault. It appears that many places around the world are currently contributing millions of dollars to the preservation of plants that are not vastly popular in today’s farming programs.

No matter whether it be the selection of the next variety of rye or a Rambouillet buck, I believe the next wave needs to be genetic selection for all the performance and eating qualities that we have been focused on but we must also incorporate health into what we produce. I have contributed to the problem myself; you get that “great one—the best bull we have made yet” and then he gets sick so we treat him and then use him to breed a bunch of females. Well, not anymore. Not in our operation.

The genetic selection of the future must not include a “partnership” with big pharma. We learned that the hard way when we had 300 nanny meat goats. I purchased a herd that had applied zero natural selection for worm-resistance and it was a wreck. When you can select for these traits, why be at the mercy of drugs to achieve a healthy herd?

Back in the day when we started our cattle program and got into the Angus business while living in Missouri, I remember many discussions about which cattle bloodlines were more “fescue tolerant” than the others. It takes a true stockman to evaluate the performance data but also use firsthand observation of better health with certain breeding populations.

Being in Florida reminded me of a conversation I had 15 years ago with one of the great cattle breeding minds in the business on his ranch talking about genetic selection. The Adams Ranch near Fort Pierce, Florida, is known for premier Braford cattle and I will never forget Bud Adams telling me, “We don’t select the cattle; we sort up the ones that tell us they belong here. Our heifers are not going to win any shows because they have a hip structure that will allow the calf to come out.” I will never forget that cherished afternoon pickup ride around their ranch.

Genetic conversations also remind me of my two trips to Chirikof Island in Alaska where the cattle have been self-selecting since the 1850s. Their confirmation and muscle structure are somewhat different than what we have selected here in the cattle breeding world.

Mostly I think I have had a very enjoyable January because of the variety of discussions I have had with stockmen from the entire nation at these events. Make no mistake about it, the value of stockmen gathering at these events and having these discussions is as important as the genetics we select while we are there. It is no secret why it is referred to as “getting back to your roots,” the roots ultimately determine your strength and resilience.

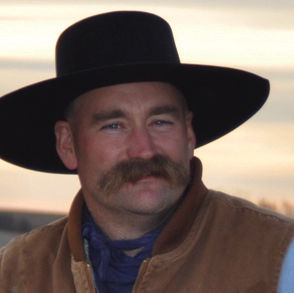

Editor’s note: The views expressed here are the author’s own and do not represent the views of High Plains Journal. Trent Loos is a sixth generation United States farmer, host of the daily radio show, Loos Tales, and founder of Faces of Agriculture, a non-profit organization putting the human element back into the production of food. Get more information at www.LoosTales.com, or email Trent at [email protected].