Record U.S. crop exports to Mexico face challenges crossing the border

The United States depends heavily on Mexico for exports of corn, soybeans and wheat. During crop marketing year 2023-24 (September-August), Mexico imported a record 29.3 million metric tons of grain and soybeans from the United States. That was 38% higher than 2022-23, 22% above the previous five-year average and 17% higher than the previous record set in 2021-22.

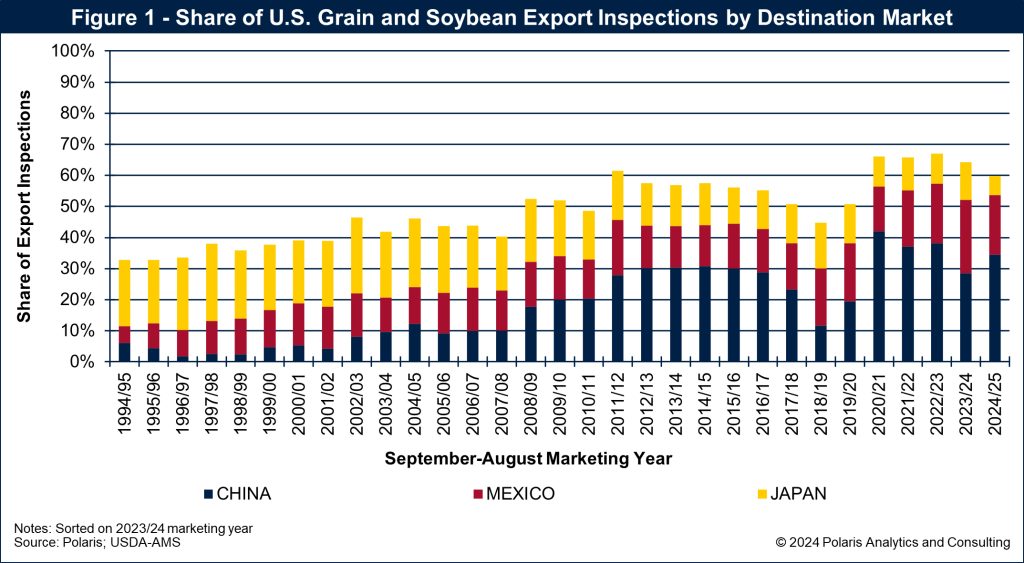

Mexico is the second largest market for U.S. grain and soybean exports, representing 19% of the volume of export inspections in the past five years and 24% during 2023-24. China is the largest market for U.S. corn and soybean exports, taking about one-third of the U.S. export volume the past five years, and Japan is the third largest with more than 18% market share. Combined, the three countries represent about 60% of U.S. exports annually.

U.S. export shares to the top three countries are shown in Figure 1.

Export pace to Mexico has been torrent

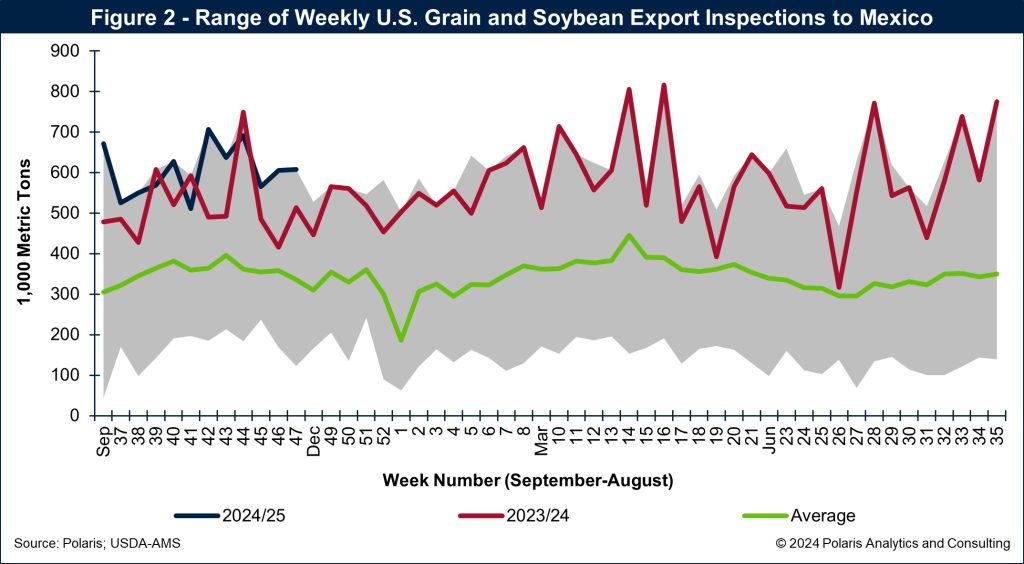

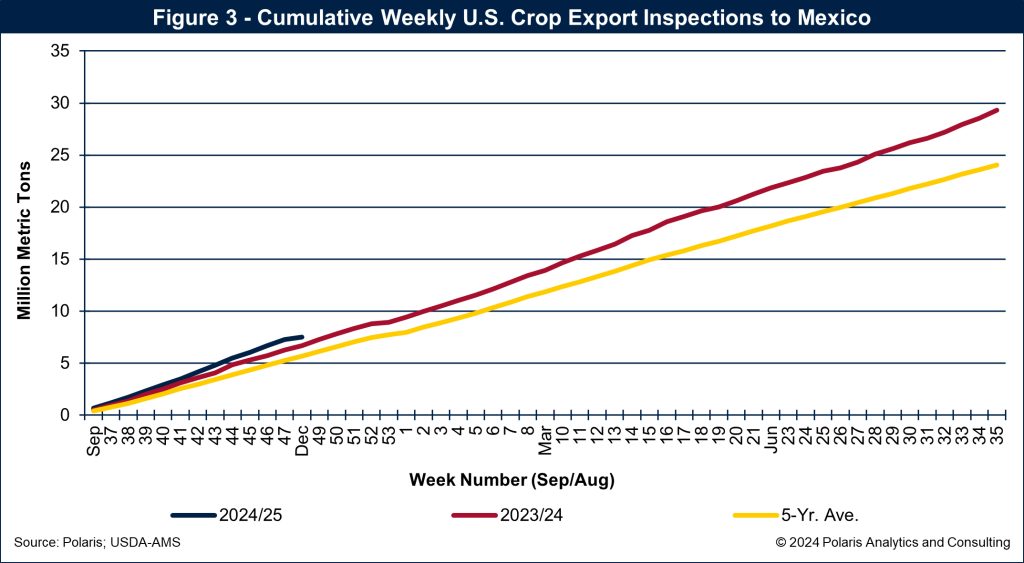

Mexico has not slowed its pace of importing grains and soybeans from the U.S. Through the first 12 weeks of the September to August crop marketing year, export inspections to Mexico have set weekly records over nine of those weeks. The current weekly pace averages 250% above the historical weekly average pace.

Through late November, cumulative export inspections to Mexico have totaled 7.5 million metric tons and are running 12% ahead of the export pace of 2023-24 and 32% above average.

The U.S. export program has more room to run with outstanding sales of corn, soybeans and wheat totaling more than 11 million metric tons through Nov. 28. This level of outstanding sales is a record for this time of year, and more than 8 million metric tons is corn. The pace of weekly U.S. grain and soybean export inspections to Mexico is shown in Figure 2 and cumulative exports in Figure 3.

Border crossings burdened

More than 60% of the U.S. grain and soybeans exported to Mexico move by rail. The record export programs have led to congestion and competition for space to cross the U.S.-Mexican border.

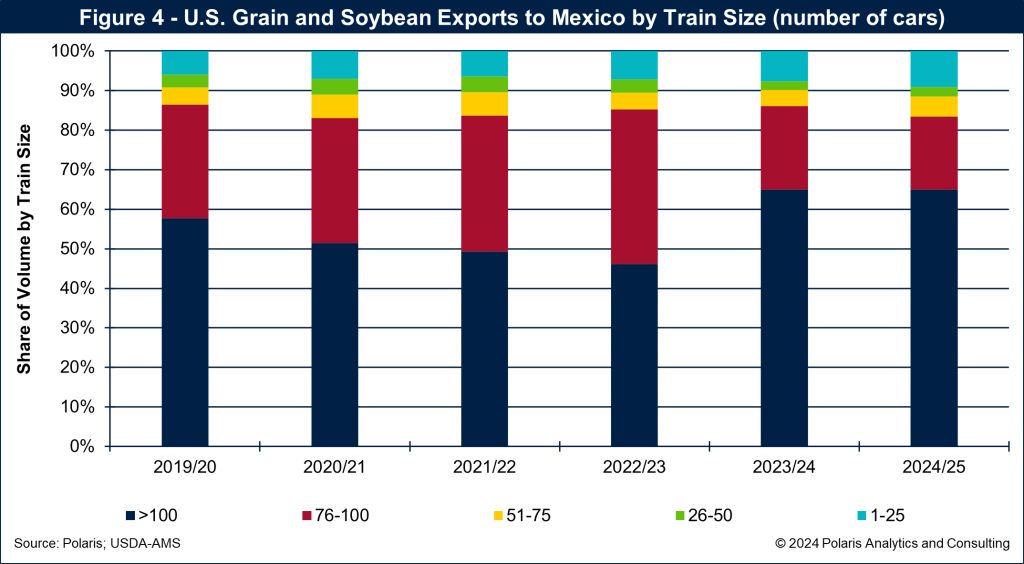

The grain and soybeans moved by rail are predominantly moved in unit or shuttle train size. From 2019-20 through 2022-23, about one-half of the export inspections moved in train sizes with 100 or more cars. In 2023-24, exports moved in train sizes of 100 or more cars surpassed 60% of the train sizes used, continuing into 2024-25. Train size used to export U.S. grain and soybeans are shown in Figure 4.

A larger train requires fewer locomotives and crew relative to the volume hauled on one train. The challenge is the sheer number of trains arriving at the border each week that need to be handed over to the Mexican rail company, be inspected by Mexico’s grain inspection service and move to final market position. The inspections alone have been a main sticking point, delaying the movement of grain into Mexico.

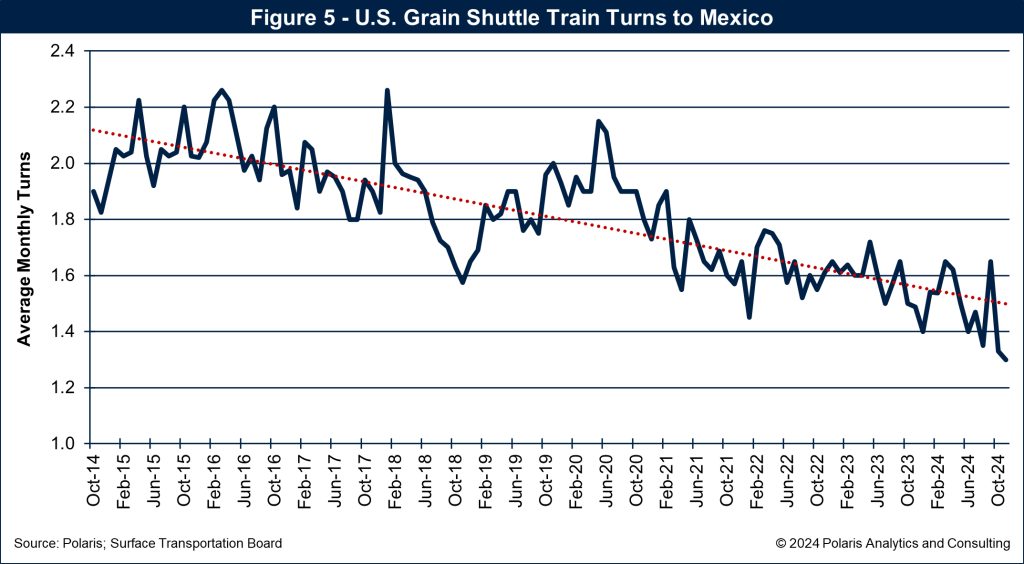

With the increased exports of to Mexico, shuttle train turns have dropped considerably. From 2015 through early 2018, shuttle train turns to Mexico averaged two turns per month, before dropping to 1.6 turns and rebounding above two in June 2020. However, since June 2020, grain shuttle train turns have been steadily slipping, and, through early November, there were about 1.3 turns per month.

With slower turns, more trains are required to haul the same volume, but exports to Mexico have been rising to record levels. With record levels and slower turns, more train capacity is required, which further exacerbates slowness crossing the border.

U.S. grain shuttle train turns to Mexico are shown in Figure 5.

Mexico has appetite for U.S. grains and soybeans, but will it survive?

Mexico has had a healthy appetite for U.S. grains and soybeans the past four years. It has become accustomed to a readily available supply in proximity across the border from the United States. Will Mexico continue to buy from the U.S. if border crossings are further challenged?

If the Trump administration imposes talked about tariffs, will it stop all flows? Mexico could buy grain and soybeans from other markets, such as Brazil, Argentina, Ukraine or Russia. However, doing so is more expensive because of the distance and cost of freight. The tradeoff for Mexico is what price those in the country will pay to buy grain or soybeans elsewhere that is less than the price of U.S. exports plus a tariff. Mexico will be challenged, and perhaps Mexico is front-loading its imports from the U.S. ahead of any tariff action.

As the second most important market for U.S. grains and soybean, the U.S. can hardly endure tariffs on exports to Mexico. For now, exports to Mexico are on a torrent pace and should be celebrated, despite slowness at the border.

Ken Eriksen can be reached at [email protected].