Twenty years of the Renewable Fuel Standard

The Renewable Fuels Standard achieves a key milestone this year, celebrating 20 years since it was first established under the Energy Policy Act of 2005. The goal of the RFS was mandating annual volumes of renewable fuel to be blended into transportation fuel, used for home heating or jet fuel as an oxygenate in gasoline and to reduce emissions.

The RFS has four renewable fuel categories: biomass-based diesel, cellulosic biofuel, advanced biofuel and total renewable fuel.

Several feedstocks are used to produce renewable fuels, including corn, sorghum, barley, wheat and sugarcane (primarily for ethanol), soybean oil (primarily used for biodiesel and renewable diesel), canola or rapeseed oil, biogenic waste oils, fats and greases, cellulosic biomass (crop residues, wood and grasses), algae and camelina sativa oil (non-food oilseed crop).

Following the establishment of the RFS, ethanol production expanded rapidly. In the United States, corn is the dominant feedstock to make ethanol.

The RFS was expanded by the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007.

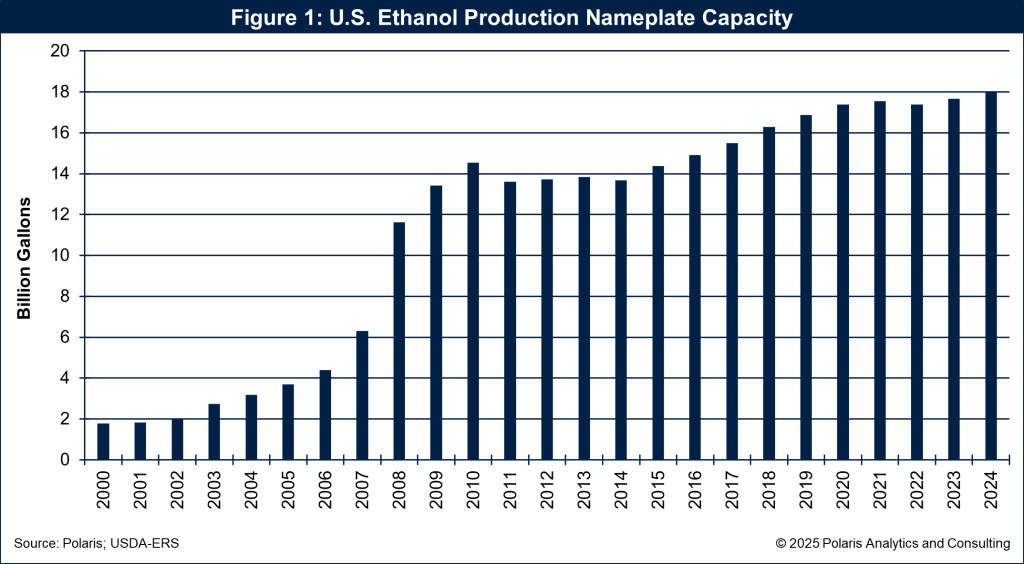

Rapid ethanol plant expansion

Ethanol was crucial as an oxygenate to displace methyl tertiary butyl ether or MTBE and help gasoline burn more completely while reducing emissions. As mandated, ethanol is blended to at least 10% (E10) of the gasoline consumed in the U.S. Some states allow gasoline to be blended above E10 to as high as 85% (E85) with ethanol.

There are 187 plants across 21 states that have nameplate capacity to produce 18 billion gallons of ethanol annually. More than one-half of the plants are in the High Plains, mostly in Iowa, Nebraska and South Dakota.

Prior to 2005, ethanol production capacity was less than 4 billion gallons annually. Because of the 2005 RFS, ethanol plant capacity expanded to more than 6 billion gallons in 2007. With the 2007 enhanced RFS, capacity leapt to more than 12 billion gallons and then slowly climbed to today’s level. The expansion of ethanol plant capacity is shown in Figure 1.

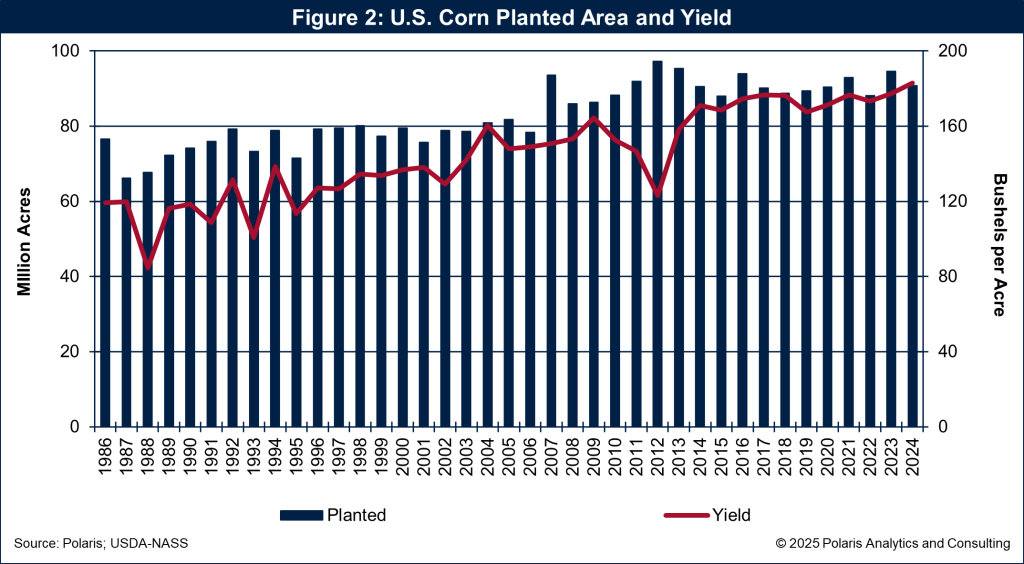

Corn fundamentals since 2005

The RFS has been a propellant to U.S. crop fundamentals. Corn is an efficient feedstock to produce ethanol, given its starch characteristics and because it is widely produced in the U.S., is storable and can be transported readily.

In 2005, U.S. corn production totaled about 11 billion bushels, increasing by 36% to 15.143 billion bushels in 2024. Over that same time, the area planted to corn expanded 11% or 9 million acres to 90.7 million in 2024. Corn yield increased 24% or 35.2 bushels per acre to183.1 bushels in 2024. U.S. corn planted area and yield is shown in Figure 2.

Corn yield improved as seed companies developed new varieties while making hybrids better. Farmers adopted improved cropping techniques and used better crop nutrients and crop protection by applying those more precisely. Technology improvements came as ethanol demand for corn sent prices higher. That led to increased research and development funding dedicated to improving crop yield.

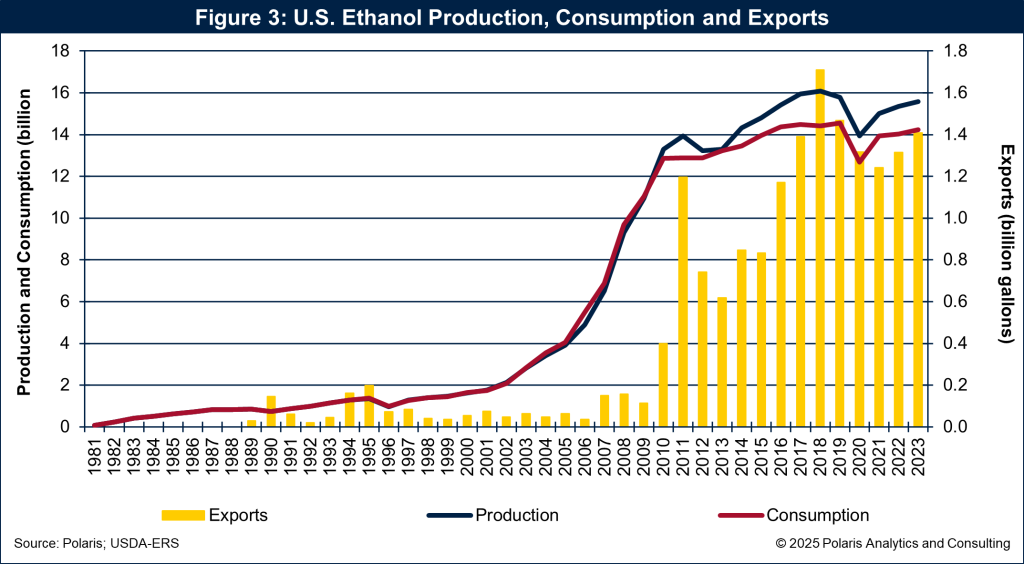

The pace of ethanol production grew from 3.9 billion gallons in 2005 and exceeded 16 billion in 2024. The domestic use of ethanol has hovered around 14 billion gallons since 2015. The residual volume was exported. In 2018, exports peaked at 1.7 billion gallons while pulling back to 1.4 billion in 2024. The production, consumption and exports of ethanol are shown in Figure 3.

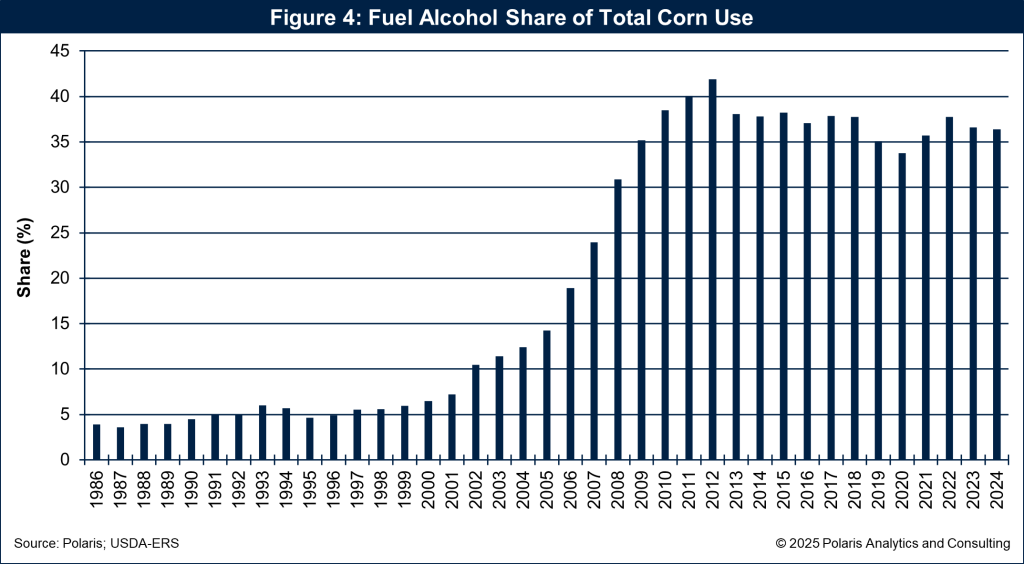

Up until 2005, the share of the corn crop used for ethanol was below 15%. With the RFS, corn share used for ethanol jumped to about 42% during the drought year of 2012. Since then, the amount of corn going to an ethanol plant slowed, while corn production continued to expand. As a result, the share of the corn crop going to an ethanol plant has pulled back to about 35% in 2024. The share of the corn crop used for ethanol production is shown in Figure 4.

With crop production improvements and the volume of corn going to an ethanol plant slowing, other users of corn such as livestock feeders, consumer packaged goods companies and international buyers have an ample supply to use.

It is more than ethanol

While the RFS rewarded farmers to plant more corn and adopt improved technology and equipment, valuable co-products came along for the ride as well. A bushel of corn offers more than 2.7 gallons of ethanol. That is not all because from the same bushel that goes through an ethanol plant, about 17 pounds of distillers dried grains with solubles (or DDGs) and 0.7 pounds of corn oil are also produced.

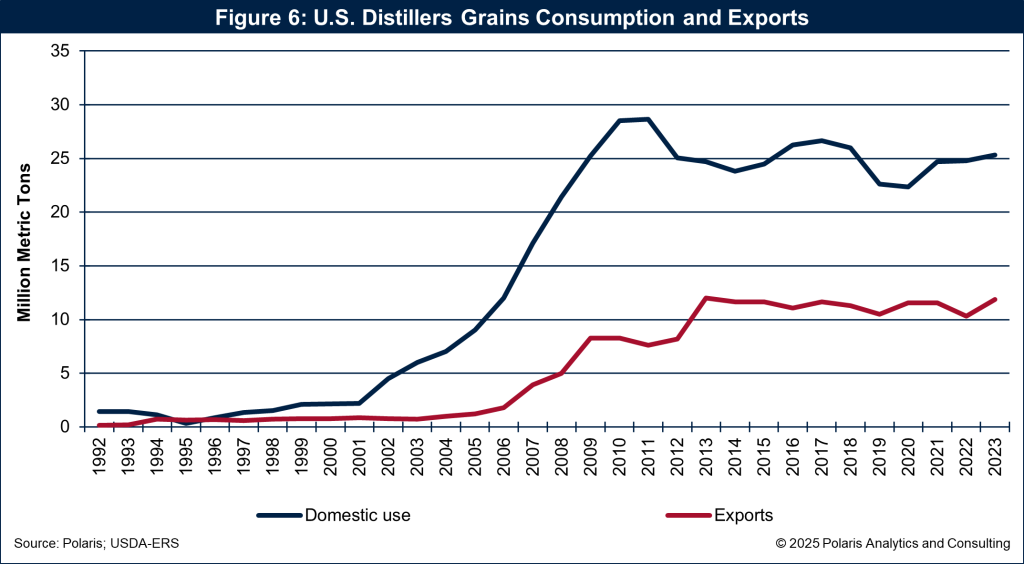

DDGs are a highly valued ingredient for livestock feeding while corn oil is used for food, feed, fuel and industrial purposes. DDGs consumption in the U.S. was less than 10 million metric tons prior to 2005. Consumption of DDGs expanded to nearly 29 million metric tons in 2010 before settling to about 25 million through 2024.

Livestock feeders around the world found DDGs to be an important feed ingredient as well. In 2005 the U.S. exported 1.2 million metric tons, surging to 8.3 million metric tons in 2009, and exceeding 10 million in 2013 where they have held that level.

The use of DDGs is shown in Figure 5.

RFS changed the map in many ways

While the RFS was a game changer for renewable fuels, it changed the map of agriculture through higher production and use of corn, soybeans and other feedstocks. The impact went beyond the fuel tank and farm. It also supported U.S. energy independence through lower use of crude oil, and quite frankly, lower imports.

Ethanol produced by corn, for example, has displaced the need for the U.S. to import crude oil that is used to make gasoline. Blending ethanol to 10% in gasoline during 2024 essentially cut crude oil imports by an equivalent of 702.6 million barrels.

The savings is calculated by presuming the U.S. consumed 137.1 billion gallons of gasoline in 2024. With ethanol’s contribution being 10% of the gasoline, the amount of ethanol used instead of gasoline would have been 13.7 billion gallons. Each barrel of crude oil (42 gallons) can produce about 19.5 gallons of gasoline. Thus, the net reduction equivalent in crude oil imports would be 702.6 million barrels annually.

What’s next for RFS and ethanol?

Ethanol has proven to be important for energy independence while lowering emissions. There is optimism of ethanol being used in more countries while being used as a jet fuel or sustainable aviation fuel. However, with each new car model, fuel mileage of internal combustible engines improves, using less gasoline for the same distance driven. Moreover, as the promise of electrical vehicles materializes with gains in market share, gasoline consumption drops further. As fuel consumption falls for automobiles, the requisite use of corn used to make ethanol also drops.

In the foreseeable future, however, ethanol has a prominent position as an important fuel while supporting

Ken Eriksen can be reached at [email protected].