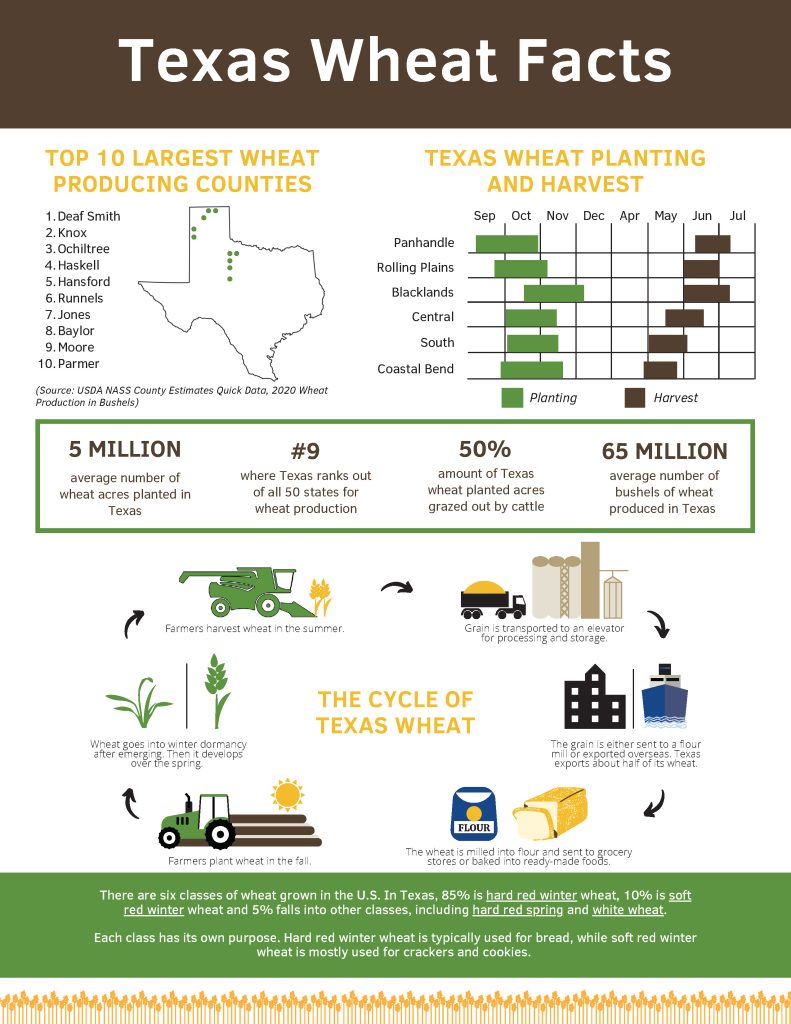

The Lone Star state has entered with realistic expectations considering Mother Nature’s fickle demeanor during the growing season as the High Plains wheat harvest gets underway.

Steelee Fischbacher, executive director for Texas Wheat Producers, said the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Agricultural Statistics Service has estimated a 2025 harvest of about 71.3 million bushels, which is down from 80.6 million bushels a year ago. NASS has estimated a statewide average of 31 bushels per acre.

Fischbacher said Texas has three prime growing regions. The Blacklands area, which includes an area from Dallas to Waco and north to the Oklahoma border, appears to have some “fairly good” production. The wheat acreage overall is smaller, but if the fields can survive late spring rains there is potential for growers to see yields at 50 to 55 bushels per acre.

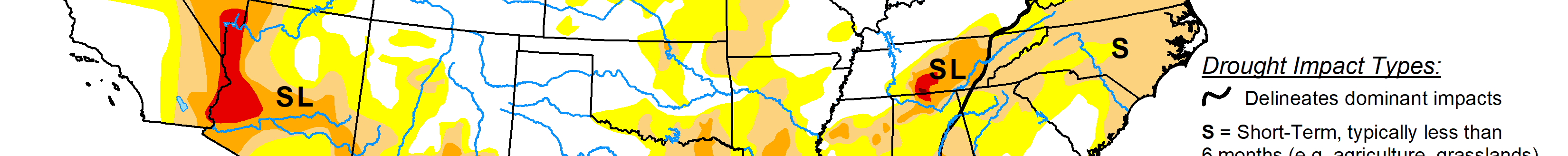

The area hardest hit by drought is in the central Texas known as the Rolling Plains region and includes the San Angelo to Wichita Falls area where fields received little or no timely moisture when the crop needed it the most. Late-season rains were too late and growers abandoned the crop and planted spring crops, she said.

Panhandle looks promising

The Panhandle region appears to have a good wheat crop this year, and farmers have several options because some growers harvest the crop for grain while others harvest it for silage to meet the needs of a growing dairy industry.

“Dryland yields will be the best we’ve seen in many years in the Panhandle,” she said. “We had timely rains and cool temperatures at the right time.”

Fischbacher said if more of the acres were harvested for grain instead of silage, that would have dramatically raised the bushel production for Texas.

Another factor in a drop in grain production was more growers who had cattle opted to make more acres available for grazing because higher beef prices outweighed low grain prices, she said. If the wheat crop was insured, they did have to pull the cattle out of the wheat pasture by March 15.

Wheat growers also are facing headaches caused by viruses in several regions of Texas and they have noted the fungal fusarium head blight, wheat streak mosaic, and triticum mosaic virus reports in nearby states of Oklahoma and Kansas, Fischbacher said.

As a result, she said, farmers were dialed into a recent field day where one of the speakers was Ken Obasa, an assistant professor and Extension specialist for Texas A&M AgriLife and based in Amarillo. Obasa said bacterial diseases are not only impacting the Panhandle, but the entire wheat-producing region. While his Extension territory is primarily the Panhandle he also has statewide responsibilities for the diagnosis of plant diseases of small grain crops as well as other field crops, including hemp, as director of the Texas High Plains Plant Disease Diagnostic Laboratory located in Amarillo.

Two yet to be designated

This year, two new bacterial diseases, which have yet to be designated, are on the rise and becoming widespread based on findings from his tactical surveillance efforts as well as the results of the analysis of samples submitted to the laboratory from different regions of Texas for disease diagnosis. He visited with producers at the ongoing field day to share and discuss his findings. He physically pulls plants out by the roots to show growers what symptoms of the new bacterial diseases to look for on the above- and below-ground parts of affected wheat plants.

For instance, he says, “premature bleaching of wheat heads which can be caused by wheat stem maggot infestation, freeze damage, as well as root rot, is also associated with the new diseases. The bleached heads often lack grain fillings.” Other symptoms that are associated with the new diseases include stunting and yellowing, both of which can be observed early in the season during the vegetative growth stages of affected wheat crops. Yellowing, in the one is mostly confined to the lower parts of affected wheat plants while the other can cause yellowing of the entire plant.

Farmers have plenty of challenges with other diseases including the wheat mosaic virus complex and rusts.

“Farmers need to pay close attention, particularly with dryland wheat,” Obasa said. “Drought and heat stress are always potential stressors, but they can mask problems and lead a producer to overgeneralize and misdiagnose an underlying problem.”

However, in irrigated fields, it is easier to recognize the manifestations of the new diseases since the impact of drought and heat stress are lesser in such production systems. The greater availability of soil moisture in irrigated field, compared with drylands, unfortunately helps to facilitate the spread of the bacterial pathogens in an infested field.

Catching it early

Because its another challenge to the wheat crop, Obasa does not want growers to miss a sign. As the crop matures, the impact is even more noticeable, noting the pre-mature bleaching in the head. Since other factors can similarly result in premature bleaching of wheat heads, diagnosis of affected plants can help to identify the real cause.

Under the current economic climate, growers need to be able to accurately identify economically important diseases, assess their impacts, and make a timely, potentially cost-saving decision, he said. A maturing crop with mostly empty head means less grain to harvest and sell; meanwhile the plant may still be drawing out moisture and nutrients that adds to the losses.

“With all the right information in hand, producers can be put in a position where they can make timely decisions,” Obasa said. “If you suspect something might be off in your field, but aren’t sure, you can get a second opinion from testing. A confirmation can inform a closer monitoring of an affected field. If it looks like the yield might not there at the end of the season, one way to minimize losses is to convert the crop’s purpose from grain to silage because to not come away with something is too costly and that’s what’s going on right now for some producers.”

Obasa’s goal is to help growers to become informed about crop diseases so they can make cost-saving decisions.

Fischbacher said depressed prices have weighed heavily on producers.

“Farmers are optimistic about production in the field but concerned about the price and cost component to raising the crop,” she said.

The capability in the Panhandle to utilize wheat as a grain or as silage has helped growers in that region to feel more optimistic, she said.

Dave Bergmeier can be reached at 620-227-1822 or [email protected].