Cotton jassid a threat to High Plains cotton

Cotton producers are already struggling with high input costs and low commodity prices, but now an invasive pest is making its way across the southeastern United States and inching closer to the High Plains. The cotton jassid is an invasive species also known as Amrasca biguttula.

Ashleigh Faris, integrated pest management coordinator and field crops Extension entomologist at Oklahoma State University, said it is native to Asia and West Africa, with its range extending from Iran to Japan and Micronesia. It is also widespread in the Indian subcontinent and some parts of Southeast Asia.

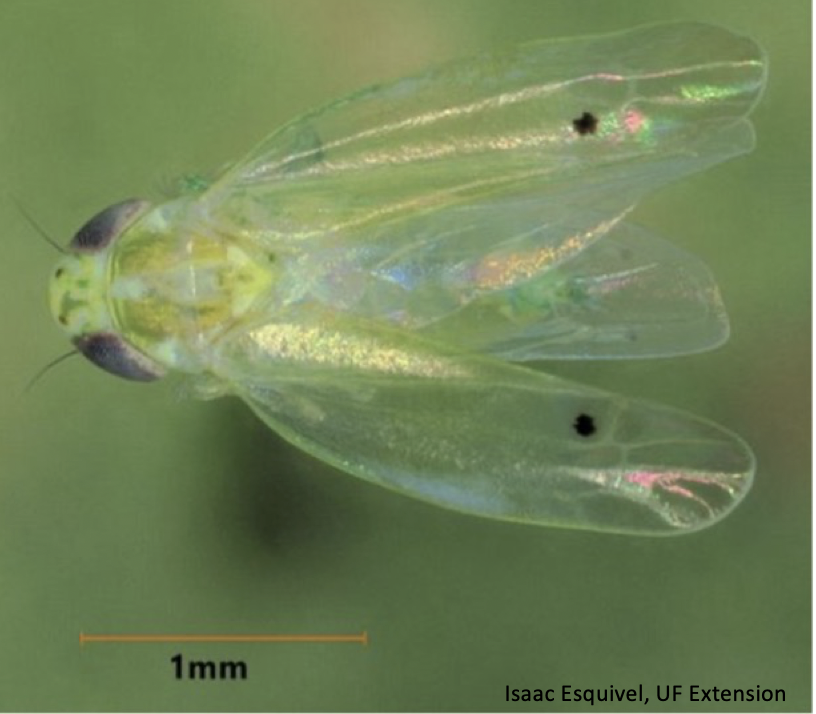

“The cotton jassid is a very small, pale green, sap-sucking leafhopper with two distinctive black spots on its wings,” Faris said. “These two black spots are what give the insect another common name, the two-spot cotton leafhopper. Nymphs, the immatures, are wingless and smaller than the adults. Due to their lack of wings, they will not bear the same two spots as the adults.”

Cotton jassid was first confirmed in the Western Hemisphere in Puerto Rico in April 2023. From there it migrated to Florida in November 2024, and in 2025, has been confirmed in Georgia, Alabama, and South Carolina.

Jenny Dudak, OSU Extension cotton specialist, said cotton jassid was confirmed in August 2025 in Texas on hibiscus plants originating from out-of-state nurseries, with one recent probable case in cotton production in the upper Gulf Coast of Texas.

“The multiple plant hosts for this pest, especially those sold in big box-stores, allow for the ease of spread across long distances,” Dudak explained. “It has the potential to spread rapidly, if undetected.”

Damage and scouting

Although it is mostly tied to damage in cotton plants, Faris said cotton jassid will feed on other malvaceous plants like okra, hibiscus, as well as other trees and shrubs in this group. She said it also has been documented on eggplant and will attack sunflowers, potatoes and legume crops. Faris said it is a threat to cotton field because of its sucking and feeding behavior.

“The cotton jassid will feed on the underside of cotton leaves and as they feed they inject a toxin,” Faris explained. “The symptoms occur rapidly, causing defoliation and thus loss of photosynthetic abilities for the plant resulting in significant stunting and plant death. In India where the cotton jassid is a regular pest, some infestations require multiple insecticide treatments across a growing season to suppress pest populations.”

Faris said the emergence of this invasive species in the U.S. is a challenge for cotton producers and breeders, because it is unknown if any cotton jassid tolerant cultivars are available. According to Faris, in Georgia, more than 200,000 acres of cotton have been treated for the cotton jassid this season alone.

“The cotton jassid causes hopperburn—a rapid yellowing, reddening and browning that can quickly weaken plants,” Faris said. “Initially, injury symptoms may look like potassium deficiency with slight yellowing along the leaf tips and margins. Injury may also present as upward curling or cupping of the leaves. Once early symptoms are visible, leaves decline rapidly, turning red and brown.”

Faris said cotton jassid populations and hopperburn symptoms usually begin on field edges before moving into the cotton field. Because late-stage hopperburn can resemble a spider mite infestation, she recommends growers and consultants scout for the pest prior to deciding on an insecticide.

“Based on insecticide trials being conducted by Isaac Esquivel with the University of Florida; Phillip Roberts with the University of Georgia; Jeremy Greene with Clemson University; and Scott Graham with Auburn University, they are suggesting an action threshold of two cotton jassids per leaf,” Faris said. “This team suggests that when scouting, be sure you are eight to 10 rows from edges or 30 to 40 feet from ends. To scout, turn an individual expanded main stem leaf from one of the top five nodes and count immatures on the underside of the leaf.”

Furthermore, Faris recommends sampling a minimum of 25 leaves across plants and average counts across the number of leaves sampled.

Treatment and outlook

“The insecticide trials out of the southeastern U.S. are showing that we do have options with good efficacy,” Faris said. “In terms of management, multiple products seem to provide good effectiveness. Rates are still being testing but so far Bidrin has been consistent in multiple trials across Florida, Georgia and South Carolina, but may be difficult if whiteflies are an issue. Centric, Carbine and Transform seem to be consistent as well. One product that should not be used is Bifenthrin, which has proven not to be effective across multiple trials. Growers should know that thresholds, as well as scouting and management guidance will likely change and evolve as we learn more about this pest.”

On the positive side, with the stage High Plains cotton is in right now, it is unlikely to affect this year’s fields. However, next year could be a different story as the cotton jassid can overwinter in a warmer climate, like Texas.

“The severe damage observed from the cotton jassid in the southeastern areas of the Cotton Belt is unlikely in Oklahoma in 2025 because we are around a month away from harvest-aid applications beginning,” Dudak said. “However, cotton producers need to be vigilant and react quickly to this pest. It has negatively impacted the bottom line of cotton producers in other regions of the U.S. and is something we need to be prepared for and take seriously in Oklahoma.”

Dudak said continued transparency and collaboration with neighboring states that are monitoring the presence of this pest will be key to ensuring the U.S. cotton industry can face this challenge head on.

“We are fortunate to have colleagues across the Cotton Belt focusing on identifying and controlling this pest,” Dudak said. “If conditions are favorable for this pest to reach Oklahoma cotton acres, we will be better prepared to control the cotton jassid. Since the economic threshold is low, diligent scouting is necessary to minimize damage and slow the spread of the pest.”

Producers should report pest sightings to their state Extension entomologist or their state department of agriculture.

Lacey Vilhauer can be reached at 620-227-1871 or [email protected].

PHOTO: Cotton jassid. (Photo courtesy Isaac Esquivel, University of Florida.)