Farmer, rancher discuss sustainability at Ag Media Summit

Sustainability can mean a dozen different things to farmers and ranchers. For ranchers it could be having something to pass on to future generations with grazing lands that can support stocking rates, while for farmers it could mean a legacy or just being profitable enough to put the next crop in the ground.

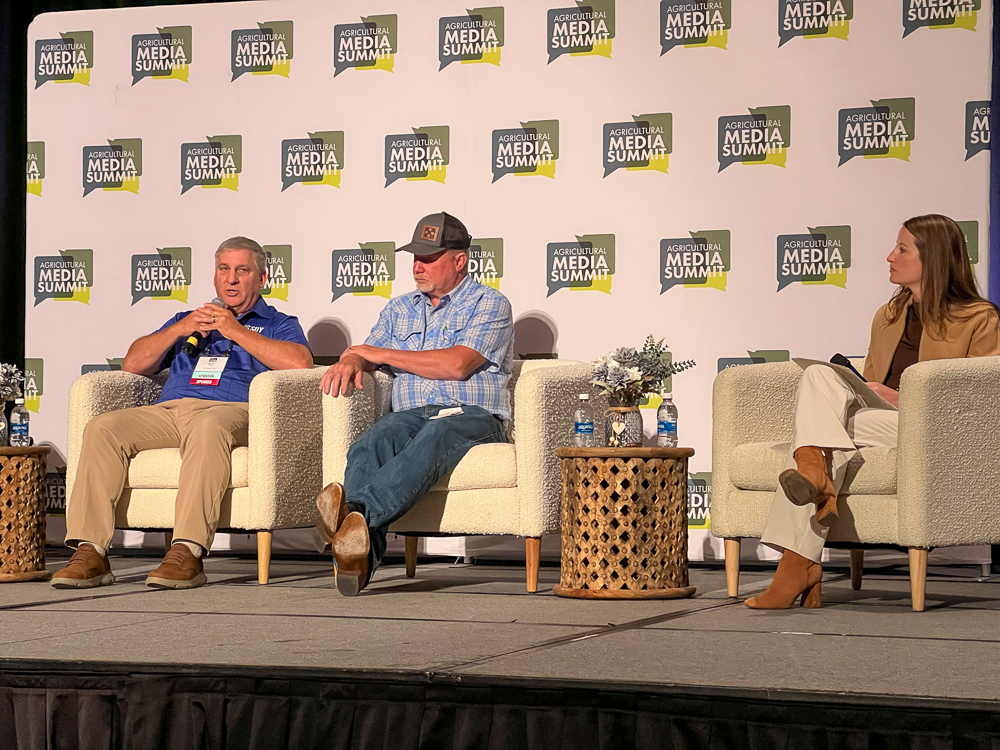

At the recent Agricultural Media Summit in Rogers, Arkansas, a newsmaker panel featured Charlie Besher, a Missouri rancher who raises registered Herefords and serves as a board member of the U.S. Roundtable for Sustainable Beef, and Robert Petter, an Arkansas soybean and rice producer, who’s serving his second three-year term as a United States Soybean Board director.

Sustainability has become one of those buzzwords everyone loves to hate. It’s almost become meaningless because it’s so overused. For Bresher, sustainability means resiliency.

“Is my operation going to be here for the next generation, my grandkids, their kids?” he said. “That, to me, is my goal in my sustainability program that we’ve got on our operation, is to have that there for our generations to come.”

Increasing wildlife and water quality on his operation is important, too. So is having buffer zones along creek banks and keeping cattle out of the streams.

“In a beef operation, it’s a lot different than it is on row crop operations,” he said. “We’ve got animals out there grazing, and we’ve got to control their impact. To me, the resiliency part is what drives it home. I would rather replace the sustainability with the word resiliency.”

For Petter, sustainability is what “we as farmers have been doing almost forever, long before there was the word sustainability.”

“It’s personal, it’s where we were raised. It’s where we’re raising our family. It’s how we make our living and to protect the soil and the crops and the animals and the water and the air,” Petter said. “It’s all around us that’s the most important thing that I can think of, and we do it just because that’s where we are.”

Consumers want what they want and producers are tasked with giving them what they need.

“I think we are doing a great job at that,” Petter said. “We need your help in telling that story, and the more we can, I think the better off we’ll be.”

Conservation a must

Both operations use conservation practices. Petter uses many practices on the operation, and irrigation is front of mind. He said everyone is familiar with no-till and other practices, but the next step after is forgotten.

“In the early 80s, we had an extreme drought here in Arkansas, and most of the farmers jokingly made a comment, ‘I sure wish I had some of that water that we had back in the spring when it was too wet,’” he said. “It took us a few years, but we realized that if we can take some of our least productive ground and create on-farm water storage facilities that we would have good, clean, pure, reoccurring, natural rainwater. And that’s what we’ve been doing on our farm.”

Starting in November each year, Petter begins collecting snow melt and any kind of rain runoff.

“That’s what they’re using at home today irrigating crops on the farm—is that just good, old, clean rainwater that fell,” he said. “It just really comes full circle when you’re reusing and utilizing something that’s natural. I’m not pumping it out of the ground.”

Petter believes water reuse is a positive story to share.

“When I try to talk more in depth on that internationally, people just really, really love that story, because we, as in the U.S., are trying so hard to be sustainable and to differentiate our U.S. soy product,” he said. “And I’ll say from other commodities as well, because we need to hear from everybody, from all commodities that are doing the same thing. We can tell our story, and other peoples are looking for that every day, from us.”

Innovation works

By investing in the farm, Petter has been able to nearly double yields—going from 30 bushels per acre average to “pushing closer to 60.”

“We’re creating shorter seasons, less inputs, and less inputs typically mean a greater financial ability at the end of the year to show profit,” he said.

Petter has also invested in technology.

“You’ve all heard the saying, ‘I have an app for that.’ Well, I had an app for that,” he said. “So, I’m sitting here four hours away from home, or I could be in China or Japan or wherever, and I need to irrigate I can go to the app on the phone, and I can turn on some back home, take that water and put it on the crops.”

He has sensors that can tell him how much moisture is available up to 18 inches underground.

Operational practices

Like Petter, Besher took a hard look at his operation and his native grass pastures. He evaluated the growth curve of his fescue grass and recognized the annual fight that comes along with it.

“If you look at the growth curve of the fescue in the summer months, it’s pretty much normal. It’s not doing much,” he said. “And to make us more sustainable, we had to come up with something that we could stockpile our fescues for the wintertime to cut down our stored forages.”

Besher started looking at other forages and thought a one-season grass could be a fit. Change was small with just 20 acres.

“We started in 2018 planning for this, and we did our first seeding in 2019, and we went into it very slow, because you’ve got to take the land out of operation for one complete year,” he said. “We were grazing it by the next May in 2020, and just with a little amount that we had about established on our property, we could take those animals off the fescue in May.”

This allowed the fescue to grass a rest and “store” that forage for winter and they were able to not have to feed until January or February and that also improved the operation’s bottom line.

“We have not put any commercial fertilizer on our operation since 2015,” Besher said. “With our tight margins, sometimes that can be whether we’re going to make a profit or not. That has really made us more sustainable on our operation.”

When he began putting in the native grasses, he sprayed and killed his best fescue field and it looked bare until mid-July 2019 when the seedlings started growing.

Sustainability has to be a win-win-win situation for his operation, Petter said.

“It’s got to work for the environment. Obviously, it’s got to answer the questions that the consumer wants,” he said. “We’ve got to provide what they need, but also that sustainable practice has to be something that we can incorporate.”

Most operators are interested in hearing about new sustainable practices others may have, but ultimately it is a personal decision. There are economic considerations too.

“Just because somebody is very passionate about a particular type of sustainable practice doesn’t mean that it’s affordable for us to incorporate it,” Petter said. “So, it’s really got to be a win-win-win situation.”

Have an open mind and evaluate

Both producers have had successes in changing their thoughts or procedures on their operations, but they also had practices that didn’t work or make sense for them to continue.

For Besher, it was a cost-share nutrient management barn—or feeding his cattle hay in the barn on a concrete floor. All the manure and hay had to be hauled out and spread somewhere.

“It takes a manure spreader. It takes a tractor to load (it). It takes a tractor to spread it,” he said. “When I can take that animal out in the field and unroll my hay, and that cow can spread that manure. I’m not happy to do it. We have two farms with nutrient management barns, and neither one of them have been used for the last three years.”

On Petter’s farm it had to do with cover crops. There’s a lot of rice in the southern regions of the U.S., and he believes the rice stover needs to be classified as a cover crop because the straw holds moisture.

“You can’t hang on to it in the winter because it’s wet,” he said. “It takes a lot longer in spring for it to dry out. That’s probably one thing that does not work in the South, which is very, very big in the north, but it’s just not working as great here.”

Consumers’ wants and needs and the role the environment plays in agriculture remains important to producers—regardless if they’re farmers or ranchers. Both Petter and Besher are involved in national organizations for their respective industries and those help spread a unified message and help raise awareness for improvements. For Besher, he’s been involved with the conversation regarding greenhouse gas emissions with USRSB.

“If you look at our cattle they produce methane. How much carbon are we sequestering by proper land management? That’s an unknown. Nobody’s able to physically measure it,” he said. “How can we manage it?”

Besher is involved with a program with Purina that now measures methane. Bi-monthly people come to his operation and gather information.

“I think it’s telling the story of what we’re doing on our operations. We want this. We want to protect this land for generations down the road. We’re not there to destroy something. We want to help,” he said. “And we’re doing that through carbon sequestration.”

Cattle producers are helping to put carbon back into the soil.

“We’re growing organic matter in the soil. We’re putting carbon back into the soil by doing that. We got the hoof action of the cows out on the field,” he said. “We’ve still got those same practices. We just need to tell a story a lot better.”

Kylene Scott can be reached at 620-227-1804 or [email protected].

(Journal photo by Kylene Scott.)