Sorghum has many advantages over other staple crops and Nate Blum will remind you of them at the drop of a hat. Sorghum is a “resource-conserving grain that is a friend to both soil and water,” according to the website of Blum’s nonprofit foundation, Sorghum United, which promotes and supports more sorghum cultivation both here and overseas.

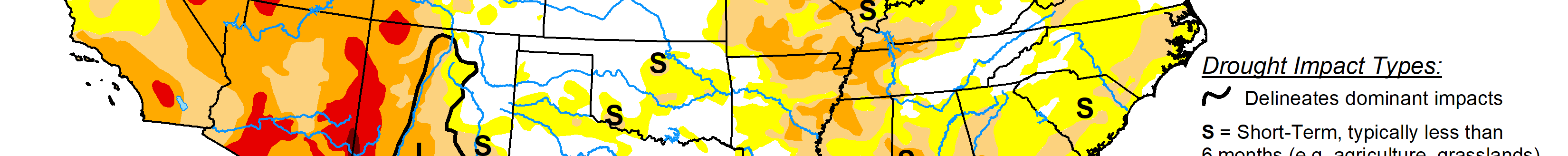

Sorghum resists heat and drought and requires 30% less water than comparable grains, which makes it ideal for water-stressed and arid parts of the planet. “That’s an annual savings so significant, it could supply the water usage of over 16 million homes,” according to the website.

Sorghum’s nutritional benefits are important for both humans and animals, proponents say. It has high antioxidant content and is rich in fiber, which supports gut health and can help manage weight and blood sugar levels. It’s a naturally gluten-free grain and a source of essential B vitamins, iron, magnesium, copper, and phosphorus, making it a nutritious option for various diets and for those with celiac disease.

Pictured above is sorghum and drone — credit Sarah Clarry. (Photo by Pixabay.)

Market acceptance

In the United States, acceptance of sorghum is growing, albeit slowly. By 2020, about 1,400 branded food items included sorghum as an ingredient, compared to 300 in 2015, according to U.S. Department of Agriculture figures cited in FoodNavigator. (That figure is 1,600, according to the Whole Grains Council.)

Still, sorghum currently remains a much smaller player on the U.S. ag stage than corn or soybeans. Its 2024-25 production is estimated at 400 to 450 million bushels, compared to 16.7 billion bushels for corn and 4.3 billion bushels for soybeans.

According to USDA, that still is enough to make the U.S. the No. 3 producer globally, behind Nigeria and Sudan. Major sorghum-producing states include Kansas, Texas, Nebraska, and Oklahoma. In a single four-year period, the Nebraska Sorghum Board noted that sorghum acreage increased by 15%.

Globally, Mexico, Ethiopia, India, Brazil, Australia, and Argentina are also major producers, with India moving up in the rankings. Sorghum’s advantages make it well-suited to India’s ag sector, with its small plots and water scarcity issues. India ranked as the No. 6 sorghum producer in the 2023 season and was forecast to become the No. 3 producer in the 2024-25 season.

China’s connection

Sorghum does share one disadvantage with some other staple grains, though: Dependence on the Chinese market. It is grown on more acres in China than rice, said Blum, making China, too, a major producer. But only 17% of total Chinese land area is arable. As a result, China buys about 90% of the entire global stock of sorghum. About 80% of what China buys goes toward animal feed. The rest goes to make baiju, a liquor very popular in certain Chinese provinces that is both fermented and distilled in a multi-stage process.

That dominance means China effectively controls the world sorghum price. And as with soybeans, China is punishing U.S. sorghum growers for President Donald Trump’s trade policies and tariffs. China’s purchases of sorghum from the U.S. dropped by 97% in 2025. It just recently approved Brazilian sorghum for purchase and is investing in South American ag infrastructure.

“Commodity markets are important, but they all share the same problem: Farmers don’t control the price,” Blum said. It’s the same problem that soybeans have. Until this year, when China’s soybean purchases ceased due to its trade war with the U.S., China bought as much as 93% of the U.S. soybean crop. Soybeans were our single biggest export to China by dollar value. A few short years ago, said Blum, every third row of U.S. soybeans went to China.

Rotational benefit

Blum sees sorghum promotion as a big part of the answer to monocropping. Planting sorghum in a three-way rotation with corn and soybeans is good for soil health, he says, citing studies that show increases in corn yields after sorghum is planted on the same plot. It’s also good for spreading farmers’ risk among more than one crop, making them less reliant on prices for a single commodity.

“Unnecessary competition between crop advocacy groups comes at the expense of farmers,” Blum says. While soybean growers are now “learning the lesson” of China’s predatory trade practices, “other commodities have largely failed to learn the lesson.”

Blum notes the importance of education and recognition by groups like the United Nations. In 2013, the UN launched the International Year of Quinoa. It succeeded in drawing attention to the nutritious South American seed, which acts like a grain and is marketed like one. In 2013, quinoa production was about 70,000 tons in the Andean region. South American associations of quinoa producers also came together to promote it. By 2023, global production had almost doubled to 112,251 tons, with Peru and Bolivia accounting for 62% and 37% of the total, respectively.

It is always a challenge

But it’s not clear how sorghum can avoid the same market development promises and pitfalls as other grains. Quinoa exploded in popularity in rich countries to such an extent that some producing countries complained that their own poor were being priced out of a nutritious staple food.

In 2023, the UN announced the International Year of Millets (of which sorghum is one). While the announcement has not had the same dramatic effect on sorghum as on quinoa, it has brought a spike in production.

Sorghum United has broad goals, including “a world where sorghum and millet are at the heart of sustainable agriculture-driving transformative change toward climate resilience and global food security.”

The word is getting out, and Blum said sorghum is getting interest and support in Kenya, Zimbabwe, Nigeria, Ghana, Tunisia, Zambia, and other countries where its advantages make it stand out.

“It’s no silver bullet—but it may be the casing on a silver bullet,” he said. The foundation has expanded to 41 countries. Sorghum seems certain to play a much larger part in ag markets in the future. Blum admits it’s a “long game.” “We’re talking about inter-generational change; it may take more than one generation.”

“Whether it’s beer, baiju or bread, sorghum can do anything any other grain can do—and it can do it more sustainably.”

David Murray can be reached at journal@hpj.com.