Records are meant to be broken—that timeless saying rings especially true this year—as United States farmers shattered previous marks with a record corn harvest and bulging grain supplies, even as storage capacity hits new highs.

With another historic harvest on the books, the next question becomes whether the nation’s storage system can keep pace with the scale of today’s grain production.

Anticipating large crops, storage capacity expands to record levels

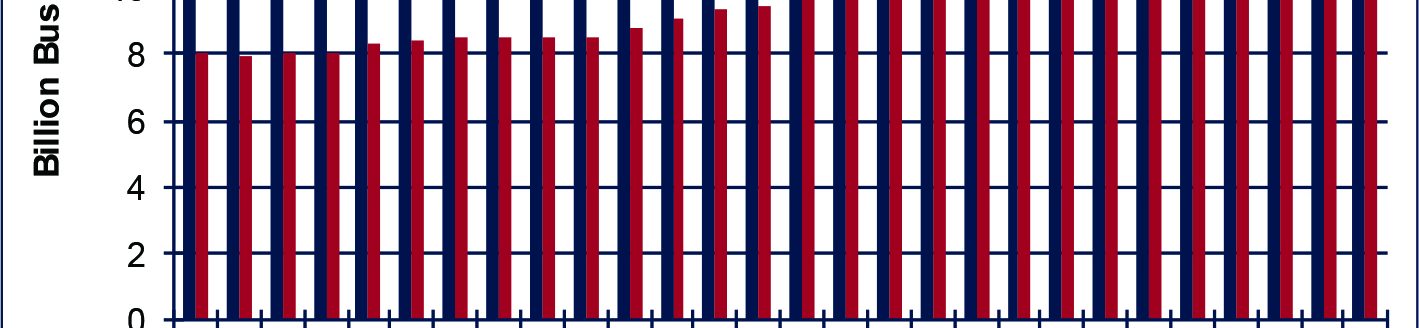

Grain storage capacity across the U.S. totaled a record 25.5 billion bushels on Dec. 1, an increase of 56 million or two-tenths of one percent from the previous year, according to the National Agricultural Statistics Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture as reported in its December “Grain Stocks” report.

In the December quarterly report, NASS updated grain storage capacity by location, on-farm and off-farm. Farmers added 25 million bushels of grain storage capacity on their farms during 2025 to 13.6 billion bushels. Over the previous five years farmers increased on-farm capacity an average of 12 million bushels per year.

Off-farm commercial storage expanded 31 million bushels during 2025 to 11.9 billion bushels as of Dec. 1. Commercial grain handlers increased storage capacity an average of 44 million bushels per year during the previous five years.

The share of capacity is unchanged since 2023 with on-farm having 53% of the capacity and off-farm at 47%. Grain storage capacity by location as of Dec. 1 is shown in Figure 1.

While national totals tell one story, the storage pressures, and opportunities, become even more evident when the focus shifts to the High Plains.

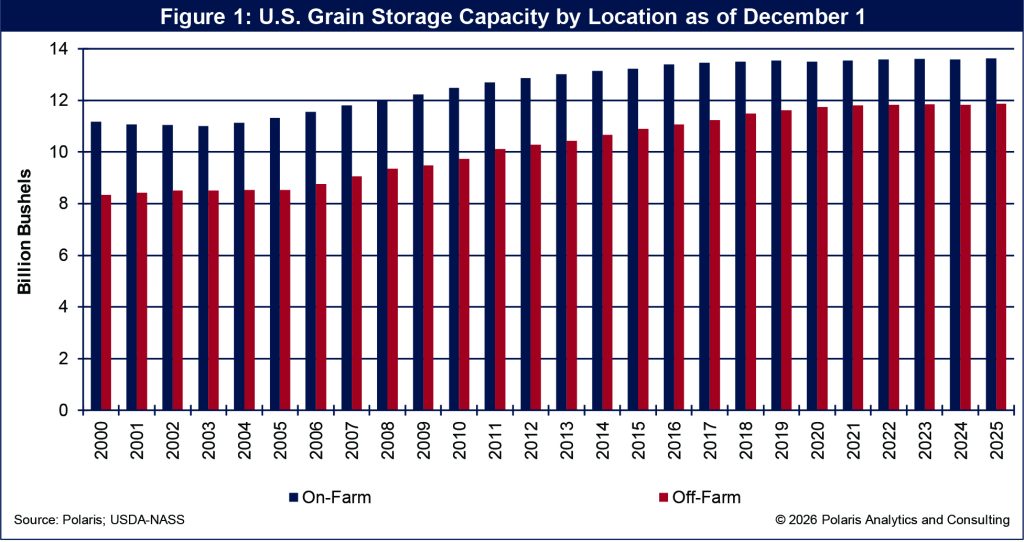

Across the High Plains, grain storage capacity totaled 11,761 million bushels as of Dec. 1, an increase of 20 million bushels. On-farm storage totaled 5,875 million bushels while off-farm totaled 5,886 million bushels, each increasing 20 million bushels during 2025 while off-farm was record large. Grain storage capacity by location across the High Plains is shown in Figure 2.

Grain storage capacity in the High Plains represents 46% of total U.S. capacity, 43% of total on-farm and nearly one-half of all off-farm capacity.

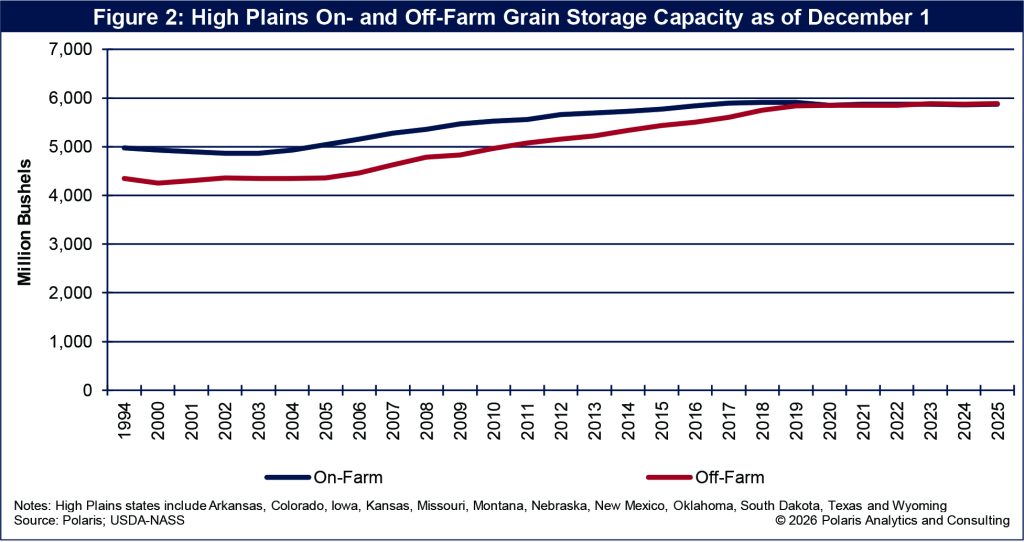

That regional capacity is not distributed evenly, and the state-by-state picture reveals how concentrated storage has become. Iowa’s grain storage capacity for example, was more than 30% of capacity across the High Plains during 2025, followed by Nebraska with nearly 19%, Kansas with 14% and South Dakota at 10% as shown in Figure 3.

Storage distribution helps explain many of the merchandising, logistics and harvest‑time bottlenecks seen across the region.

Grain supplies record large

Storage capacity is only half of the equation; the other half is the sheer volume of grain needing to be stored, and this year, supplies surpassed nearly every expectation.

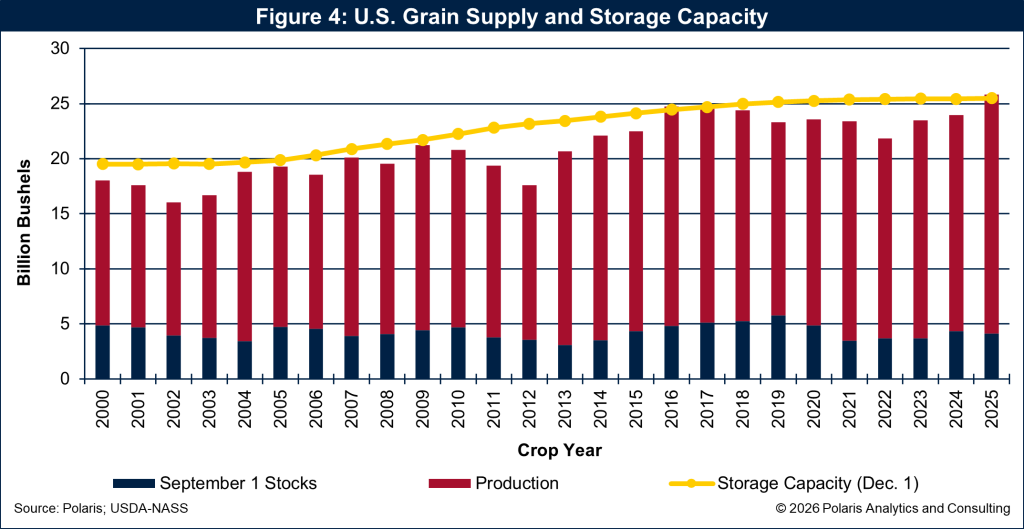

This year’s grain supplies, Sept. 1 grain stocks plus corn, sorghum and soybean production were record large at 25,845 million bushels, an increase of 1,902 million bushels or 8% from 2024. Grain stocks on Sept. 1 totaled 4,114 million bushels, a decrease of 229 million bushels from a year ago.

The surge in supplies was led by a corn crop that kept getting larger on more harvested area and higher yields resulting in an astonishing harvest of more than 17 billion bushels as pegged by USDA-NASS. Taken together, corn, sorghum and soybean harvest totaled 21,731 million bushels, an increase of more than 2 billion bushels or nearly 11% from 2024.

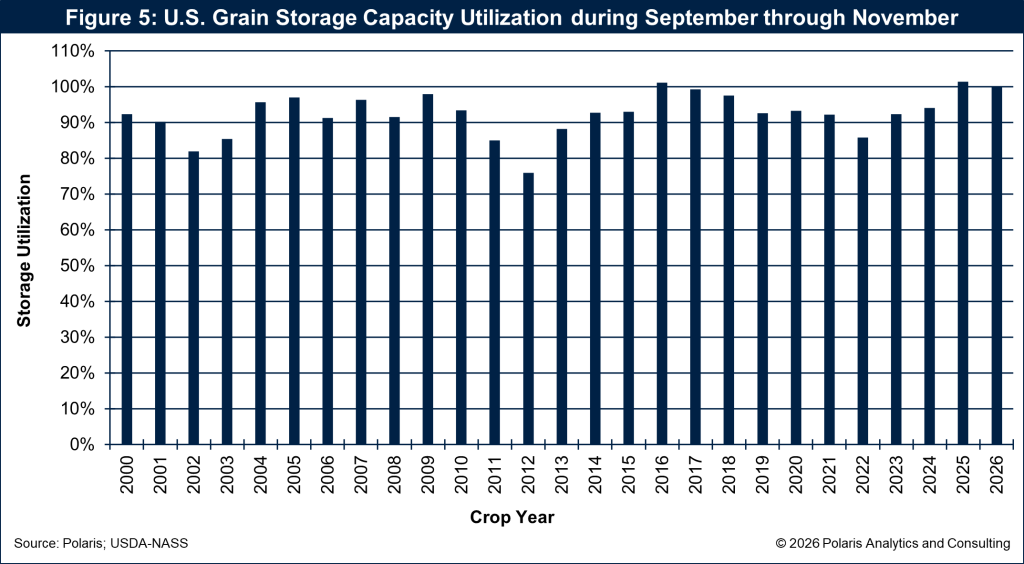

Grain supplies during the September through November crop quarter exceeded available storage capacity across the U.S. Grain storage utilization, the percentage of grain supplies using storage capacity was 101%. The last time grain supplies exceeded grain capacity was 2016.

A rising grain utilization rate signals a need for additional storage capacity, which is what took place this year, despite higher material and construction costs and relatively poor farm and agricultural economics. Farmers and commercial grain bin operators recognized that last fall’s crop harvest was going to need additional space to hold the large crop.

However, despite record supplies, the amount of storage is not the full story as much as where the storage expanded and for what purposes. Moreover, the rate of demand consuming grain offsets excessive grain storage construction. Regardless, this year’s supply situation necessitates having adequate supplies.

Grain supplies and storage are shown in Figure 4.

Grain storage part of the grain supply chain infrastructure

These record supplies highlight the importance not only of storage volume, but also of the broader collection and inspection network that links farmers to processors and export markets.

The grain supply chain from farm to commercial grain handler to domestic processor or feeder, or to position for export relies on a dependable grain collection system.

Alejandra Castillo, president and CEO of the North American Export Grain Association, sees the grain collection system as a vital link in the grain export supply chain. “Having a modern, flexible and capable storage network is key to supporting U.S. grain exports.” According to Castillo, the “grain collection network allows the U.S. to handle a variety of crops and classes of grain while preserving crop quality and characteristics. The collection system assures buyers that what they receive is what they bought.”

The U.S. system is unique as compared to our competitors, Castillo said.

“In other countries they do not have the same inspection requirements to meet specific grade requirements like exporters in the United States,” Castillo said.

“The U.S. grain infrastructure system starts with the collection system, handling the high-quality, bountiful crops farmers harvest. It is an important part of the U.S. narrative of how participants in the export supply chain strive to deliver crops efficiently,” Castillo said. She continued by saying that “communicating and demonstrating the intricacies of the grain supply chain is important especially as grain moves through the network to the export market. Farmers have demonstrated they can produce the crops, and we need to assure those farmers that the supplies can get to global markets.”

Farmer marketing with storage

If infrastructure defines how grain moves, storage decisions at the farm level shape when it moves, and at what price.

However, decisions at the farm level come in all forms and perhaps many without adequate strategies. For farmers it is more than just planting, treating and harvesting a crop. According to Karl Setzer, Consus Ag Consulting, “farmers need to know their basis, their costs, and opportunities.”

Consus Ag Consulting works with farmers to develop marketing strategies and manage their risk.

Setzer continued by saying “without a structured marketing plan, farmers do not know what storage they really need. A marketing plan helps guide the decision making on building storage.”

The decision making process does not look at the supply and demand balance table first, rather the decisions making should start with the farm balance sheet to know what value they have.

As Setzer said, “elevators are not always going to start with the highest bid, and farmers do not have to accept that bid. Rather, farmers should have an offer that conforms with their balance sheet and opportunities for their farm.”

There is much that goes into the cost of elevators and Setzer recalls a lesson he first learned from a mentor in the business three decades ago, “the storage you have today might cost you tomorrow.” What this means for farmers is knowing your costs, understanding the cost of storage and how grain is merchandised.

“Farmers would be better served investing in marketing strategies and skills before erecting storage. For many they think storage is the marketing plan. The reality is, it can cost you more tomorrow, but a marketing strategy can set up you for the future,” said Setzer.

Storage considerations with new crop prospects

As producers and analysts weigh these marketing dynamics, attention now turns to the next crop year and the storage demands it may bring.

The act of installing new storage has a long lead time. Farmers are considering grain marketing decisions and risk management considerations, assessing crop rotations and surmising on potential yield outcomes when it comes to erecting new capacity on their farms.

Commercial grain handlers are also reviewing the same variables but also evaluating what demand downstream in the supply chain looks like, if grain and soybeans will have a carry (the deferred price is higher than the nearby price) or will be an inverse (nearby prices are higher than deferred prices) among other factors.

In the end, farmers and commercial grain handlers are dependent on when and where God showers the earth with timely rains or not, with hot, dry or moderate conditions. With that, farmers will be planting crops in the next few months and by many accounts they will plant fewer corn acres while offsetting that with more soybean acres. Presuming trend like yields, new crop production for corn, sorghum and soybeans could be nearly 20,700 million bushels, about 1 billion bushels below the harvest last fall.

Still, the Sept. 1 stocks could be more than 4,800 million bushels, nearly 700 million bushels more than 2025 and the highest level since 2020. Taken together, Sept. 1 stocks and fall production, grain supplies this coming September through November would be about 25,500 million bushels, roughly 345 million less than this year’s supply level. If there were no changes to storage capacity, then grain storage across the U.S. would be fully utilized as shown in Figure 5. It is during periods of rising utilization that storage capacity expands

It might seem premature, but one cannot be too early to consider possible storage pressures. The decision to install more capacity is best accomplished through a decision matrix, capital considerations, and adequate lead times aligning contractors, equipment and construction.

With the potential for another large crop year, the industry again faces a familiar choice: Prepare early or fall behind the next record.

Ken Eriksen can be reached at [email protected].