Roundtable shares information about protecting dairy workers from avian influenza

Industry experts discussed avian influenza and how it affects workers and animals during a roundtable hosted by the AgriSafe Learning Lab.

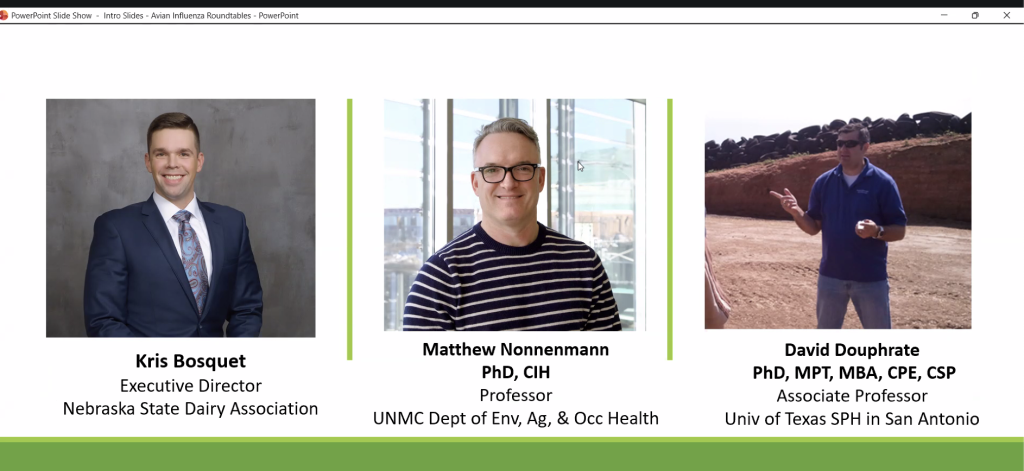

Protecting Dairy Workers from Avian Influenza featured Kris Bosquet, executive director of the Nebraska State Dairy Association; Matthew Nonnemann, professor in the University of Nebraska Medical Center’s department of environment, agriculture and occupational health; and David Douphreate, associate professor at the University of Texas School of Public Health in San Antonio.

Nonnemann said many researchers think about interventions that work well within the agricultural industry.

“What can we do to prevent accidents, incidents, injury and illness,” he said. “Our goal here, my goal, is to deliver some facts.”

Trained as an industrial hygienist, Nonnemann helped measure gasses, dust, microorganisms and then recommend control methods.

Bosquet, a lifetime Nebraskan, grew up on a dairy farm and now serves the dairy industry in his home state.

“We’ve got about six dairy processing facilities in the state, mainly on the eastern side of Nebraska, and we have about 55,000 milk cows in our state,” he said. “That’s with about 70 dairies that are licensed to sell milk in the state of Nebraska.”

The dairy industry in Nebraska has experienced consolidation over the years.

Safety first

Douphreate is on the faculty at Texas A&M University and for the past 20 years he has been directing research on agricultural worker health and safety issues, primarily in the dairy sector.

“I’m a physical therapist by clinical training, but many years ago, I chose to go into the side of prevention and what I do is conduct research and outreach along the lines of musculoskeletal injury prevention and fatality prevention as well as safety management system research,” he said.

His world was “sucked into this bird flu issue” back in 2024 and that has meant helping the industry to face and overcome a significant challenge.

Douphreate said H5N1 was first detected on a dairy farm in west Texas and had been going on before the March 2024 announcement by the federal government. Some people speculated herds were being affected as early as December 2023, he said. “That drew a lot of attention, a lot of concern.”

Avian influenza during the years it’s been tracked, globally it has about a 50% mortality rate in humans and Douphreate said that rate garners the attention of the general public and public health officials.

“We did not know the severity of what this strain of influenza was going to bring,” he said. “But it introduced a new dynamic. Here we are dealing with private businesses, livestock operations, and it was an occupational health issue, because not too long after that, the first worker was confirmed to have contracted avian influenza, and that’s what started the the media attention.”

Other ramifications

In the region where the first bird flu case was found, many dairy and beef producers were concerned because southwest Kansas, the Texas Panhandle and eastern New Mexico have one of the largest concentrations of cattle in the United States.

“The risk of transmission among cows was very high, and it spread very quickly, and it wasn’t until December of 2024 that the federal government started enacting transportation restrictions on cattle and milking testing requirements,” he said. “But by then, this had already spread to 17 states.”

Douphreate said by then it was too late to try to prevent spread among cows and workers.

“There was a public health concern, and state public health, federal public health, and the best way that I can describe it, they were having challenges gaining access to workers on farm to assess the human impact of bird flu, and that is when I was contacted,” he said. “Given all of the work that I’ve done in dairy to see if we could assess the human impact of bird flu on farms.”

According to Douphreate, dairy workers are typically the kind of people who don’t want to miss work if they’re sick. Many in the beginning had minimal flu-like symptoms for a day or two.

Impact on operations

At first there was a significant culling process, he said, but as time went on, all parties learned how to deal with it. Cows recovered after two to three weeks, and they started milking again, but that did not prevent significant economic losses among farms.

Farms have learned to deal with the disease and continue to manage it.

“I would say from the producers that I’ve spoken to, they dealt with this, and they are looking at bird flu in the rear-view mirror, but they do not know what could be coming next,” he said.

Bosquet said while cases were happening in Texas, Nebraska was thinking about how to prevent it from coming there.

“We have a lot of young stock that are raised in the dairy industry, specifically that are raised in the panhandle of Texas on calf ranches,” he said. “And at the beginning of this scenario, it didn’t look like our younger animals were affected. We were only seeing clinical signs.”

In Nebraska, they weren’t as concerned with the younger stock being negatively affected by it at first, but bringing the young heifers back to Nebraska after being raised in Texas was a concern.

A small dairy herd, played in the state’s favor, Bosquet said, contrasting it with the beef herd. “We have one of the largest feedlot industries in the entire country in Nebraska, and a lot of beef cattle move from Texas and Kansas into Nebraska to be finished, and then from there to be harvested. And so that was obviously a concern as well.”

Eventually Nebraska did have a case of H5N1 in dairy cattle, but because of testing officials were able to verify the strain was not a cross over from birds coming through the state.

“It was actually mechanical transmission of an infected animal coming into Nebraska, and so we were able to quarantine that animal and quarantine the herd,” Bosquet said. “And now we’re H5N1 free.”

Flyway path

Bosquet believes Nebraska will have a concern for H5N1 long-term because of the miles and miles of rivers and streams in the state as waterfowl fly through the state each year. There’s also been an increase in boiler production and egg laying in Nebraska, so naturally there will be higher frequencies of infection.

There were so many unknowns when the disease first came to Nebraska, and officials were unsure where to start.

“When we originally got all this interest from the scientific community, I think the perception from the industry was somewhat protectionist,” he said. “We didn’t really know what bringing the scientific community on our farms was going to mean for not just economically, for our market, but how we’re going to continue to operate.”

Bosquet said the government reassured farmers that allowing the scientific community to come in was OK—especially when it was determined pasteurized milk was safe from affected dairy cows.

Producers also rightfully had concerns for their employees as they grappled with what to do to protect them, he said.

Nonnenmann said in the past influenza traditionally didn’t infect cattle, and once it did it became a “big deal.”

“Because I like beef. I like to eat beef. We got a lot of beef in the U.S., and, of course, I like dairy too,” he said. “Between, the animal husbandry and animal production industries we have here in the Midwest and other areas—we got poultry, pigs and cattle—all within this proximity. So, it just added another concern about is this a virus we should be really worried about.”

Producers and those in the beef and dairy industries were worried about it and still are, he said. For many operators, they wonder how to make the best decisions for their farm, business, and employees. This is where scientific research and active surveillance play a role in the process.

Douphrate, however, doesn’t like the term active surveillance because it can cause the perception the government is going to come in to observe or monitor private enterprise.

“However, as with any livestock operation,” he said, “there is opportunity for animal disease, there’s opportunity for human disease, and so there has to be a mechanism somehow to early detect if something happens in these livestock operations.”

Industry has to be engaged in the process and have a seat at the table for contingency planning for the future possibility of outbreaks.

“This is one area where I feel like industry may not have been given an opportunity to have a seat at the table to discuss how do we respond to this in a most practical and realistic manner,” Douphrate said. “How do we assess not just the cow health issue, but then also any possible human health issues on our private businesses.”

He wants to engage with the producers, associations and others because “they’re the ones that can inform us how is or what is, the most effective way to assess if there is even a human, health element here, and what is the best way to respond to this?”

“That detection, the monitoring, or whatever we want to call it, we have to engage industry. They have to be involved in the process,” he said.

Kylene Scott can be reached at 620-227-1804 or [email protected].