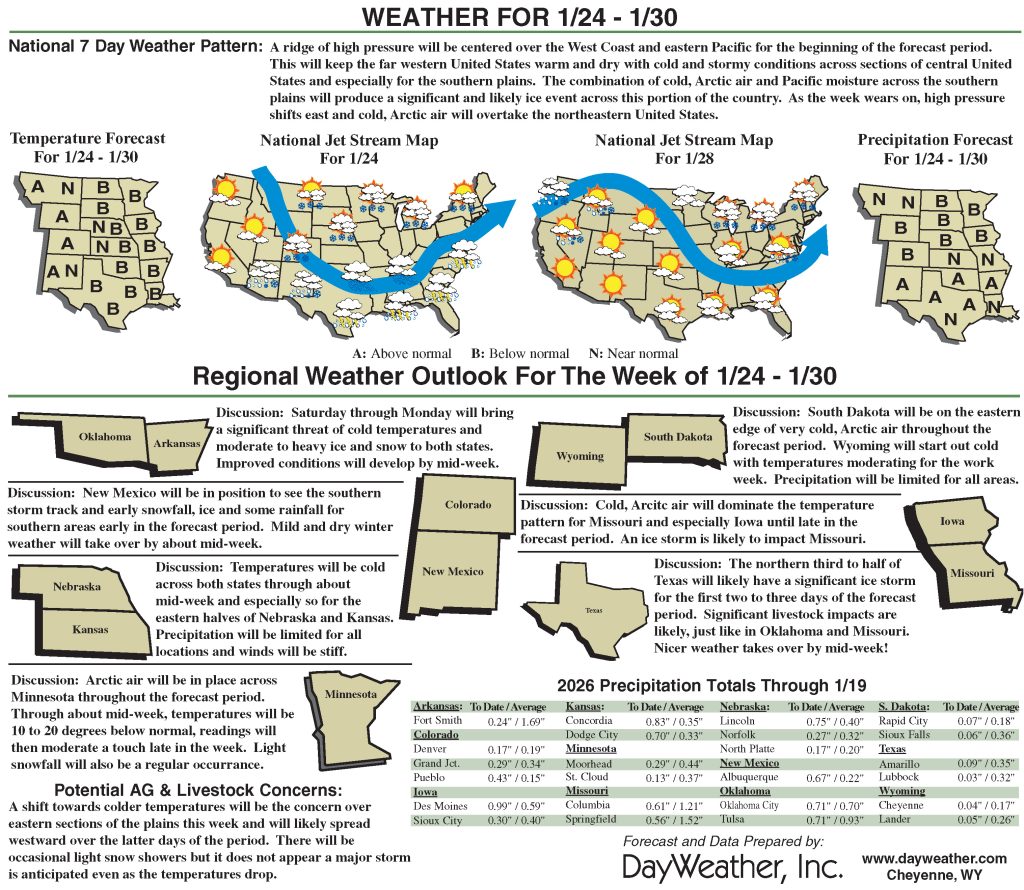

High Plains headed for cold stretch

The Lower 48 states finally settled into a more tranquil weather pattern, as a ridge of high pressure settled across the West and a deep trough developed over the East.

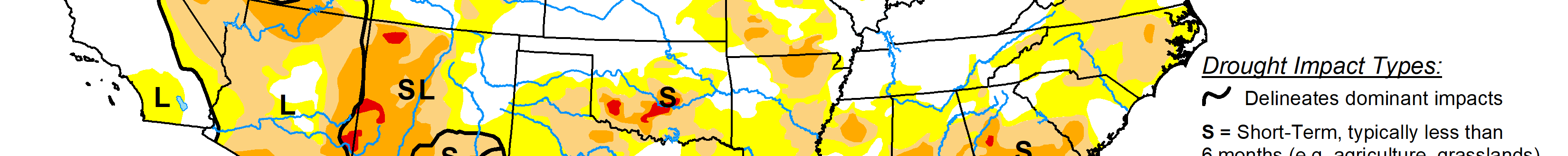

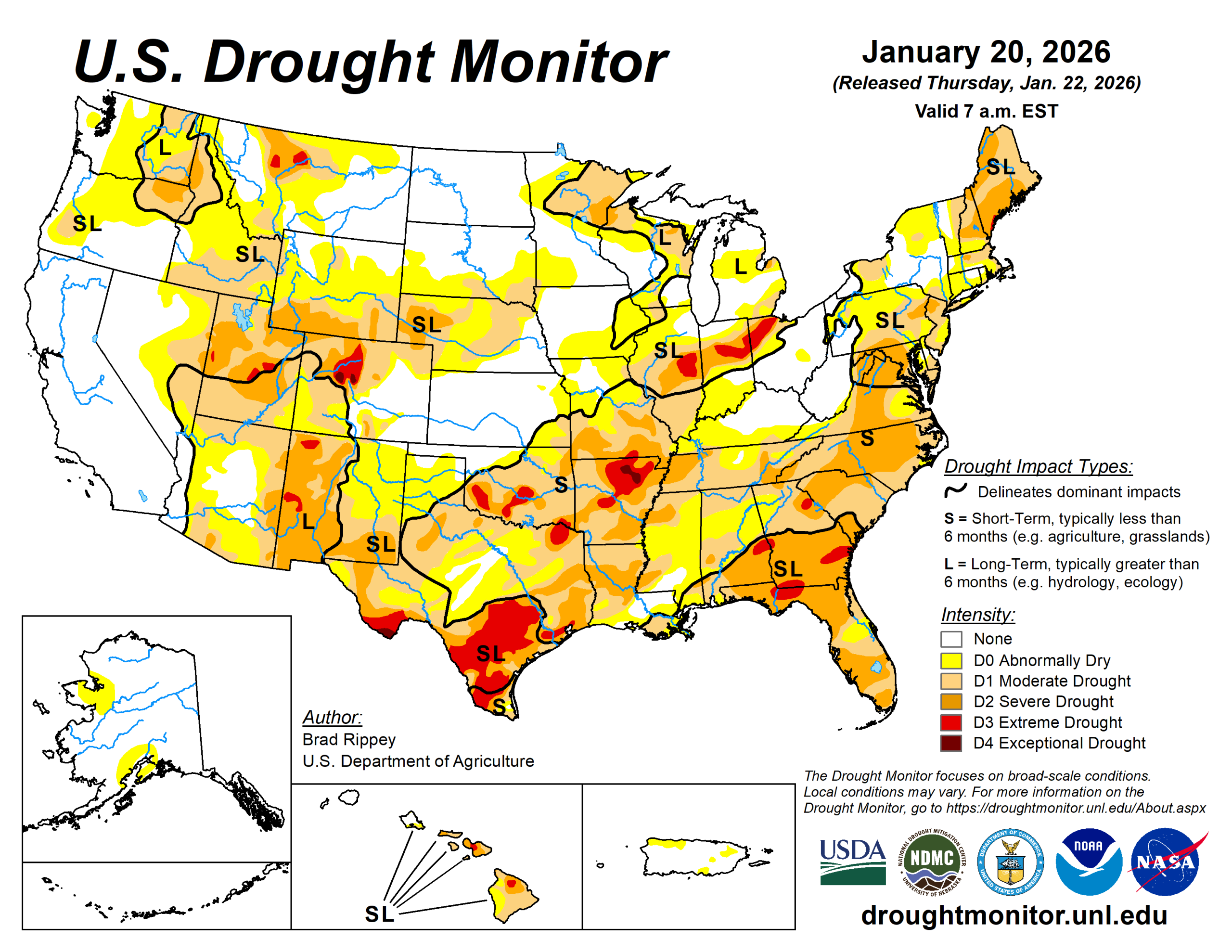

With many parts of the western United States reporting below-average snowpack for this time of year, the pattern change led to increasing concerns regarding western water supply for next summer and beyond, despite robust precipitation in many areas during the first half of the winter wet season.

Still, hydrologic signals were mixed, with California’s 154 primary intrastate reservoirs containing 25.9 million acre-feet of water (123% of the historic average) as 2026 began. Meanwhile, storage in the sprawling, multi-state Colorado River Basin stood at just under 17.3 million acre-feet (53% of average), reflecting long-term issues in part related to chronically elevated temperatures and a multi-decadal Southwestern drought.

Farther east, the Plains served as the transition zone between mild, dry weather in the West and increasingly cold conditions in the East. The Plains’ experienced dry weather, aside from wind-driven snow showers on the Northern Plains, as well as an occasionally elevated wildfire threat. Elsewhere, areas from the Mississippi Valley eastward noted cold weather, accompanied by occasional rain and snow showers.

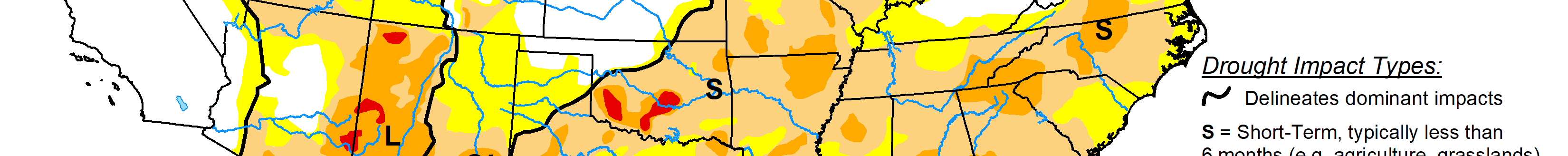

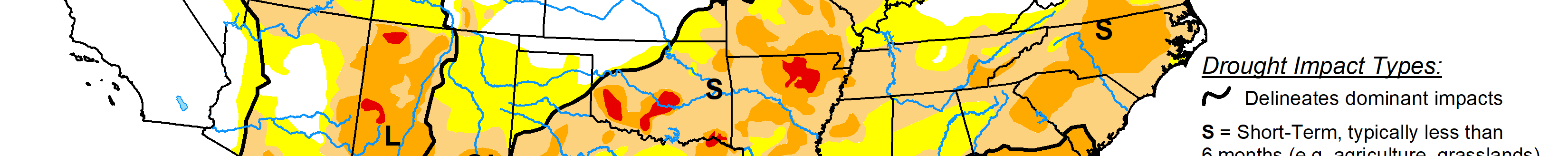

Some of the heaviest snow fell in the Great Lakes States, especially in squall-prone locations. Snow also fell along and near the Atlantic Seaboard, mainly on Jan. 17 to 18. As colder air became more entrenched in the Midwest and East, drought changes that had been occurring quickly in recent weeks, either due to flash drought or active winter storms, became more muted, with drought effectively “frozen in place” by chilly, mostly dry conditions.

During the second half of the drought-monitoring period, sub-0°F temperatures were commonly observed across the upper Midwest and neighboring regions.

The U.S. Drought Monitor is jointly produced by the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration. (Map courtesy of NDMC.)

South

Worsening drought was a common theme, especially from eastern Texas into Arkansas. A small area of exceptional drought (D4) was introduced in northern Arkansas, amid a punishing period of drought that has left pastures in extremely poor condition and has left many individuals with limited surface water supplies from ponds and streams.

Several weeks ago, in early January, the U.S. Department of Agriculture categorized Arkansas’ topsoil moisture as 46% very short to short—and mostly dry weather has prevailed since that report was compiled. From northern Arkansas, a continuous area of severe to extreme drought (D2 to D3) extended southwestward into northeastern Texas.

Much of southern Texas, as well as southern, central, and eastern Oklahoma is experiencing moderate to extreme drought (D1 to D3).

Midwest

Aside from occasional precipitation, including locally heavy snow squalls downwind of the Great Lakes, the Midwest settled into a colder, mostly dry pattern. Any changes were generally minor, with some drought deterioration noted from southern Missouri into southern Indiana.

Statewide topsoil moisture was greater than 40% very short to short in early January across Illinois and Missouri, according to USDA. Meanwhile, some minor improvements were introduced in the Great Lakes region, following recent heavy precipitation and ongoing snow showers.

High Plains

Patchy expansion of dryness and drought was noted, mainly across Nebraska, Wyoming, and southern South Dakota.

Due to periods of warm, windy weather, Nebraska reported that statewide topsoil moisture was rated 68% very short to short in early January, according to the USDA. Similarly, Wyoming’s topsoil moisture was rated 55% very short to short.

West

Over the last couple of weeks, an uncomfortable silence has settled across the West. With snowpack already below average in many Western watersheds due to this winter’s preponderance of “warm” storm systems, the mid-point of the region’s snow-accumulation season has arrived with snow-water equivalencies falling farther behind normal each day.

Among Western basins, only those located in the northern Rockies and neighboring areas are reporting widespread near-normal snowpack. By January 20, snow-water equivalencies were broadly less than 50% of average in Oregon (and portions of adjacent states) and the Southwest. More than half of the 11-state Western region—including all of California—is free of drought.

Looking ahead

From Jan. 23 to 26, an expansive and potentially dangerous winter storm will unfold from southern sections of the Rockies and Plains to the middle and southern Atlantic States, excluding areas along and near the Gulf Coast.

Much of the South will face multiple weather hazards, including wintry precipitation (snow, sleet, or freezing rain), gusty winds, and unusually low temperatures. Wintry weather may extend at least as far south as central Texas. Post-storm temperatures should fall to 10 degrees Fahrenheit or below along and north of a line from central Texas to northern Georgia, with particular concern for areas that lose electricity due to downed power lines from accumulations of ice and snow.

Farther north, sub-0°F readings will be common as far south as the central Plains and the Ohio Valley. The storm is likely to have serious agricultural impacts, including significant stress on livestock due to exposure to cold, wind, wintry precipitation, or a combination of weather extremes. Temperatures could briefly plunge to minus 30 degrees or below from North Dakota into the upper Great Lakes region.

The National Weather Service’s 6- to 10-day outlook for Jan. 27 to 31 calls for the likelihood of below-normal temperatures throughout the eastern half of the U.S., while warmer-than-normal weather will prevail in the West. Meanwhile, near- or below-normal precipitation nearly nationwide should contrast with wetter-than-normal conditions in a few areas, including coastal Texas.

Brad Rippey is with the U.S. Department of Agriculture.