Mules, the untold story

I will never forget the day, now about 17 years ago, that I brought home my first donkey. It was actually two intact male donkeys and we named them Bill and Hillary. At that time we had about four saddle horses and when I unloaded those two long ears, they trotted around the barn with huge “HELLO” and the horses, ears all perked, and as if they were in a choreographed entertainment show, all ran directly for the 5-foot fence on the south side of their pen, leaped over in beautiful harmony and didn’t stop running for a full mile. I just stood there watching them make the dust fly.

It didn’t take long and the horses came home. They were curious and soon after they all lived together without incident. Ever since that day we have had some form of long ears around the place, currently that includes a few mules. With the consistent buzz about a virus and rebuilding an economy, I would like to champion the untold story of the hero behind improving life on the planet since its creation: the mule.

Let me start with sharing just a few interesting tidbits about the history of the mule that I am willing to bet most of you had no idea about.

To the north in Asia Minor, the Hittites were the most powerful of the early horse-people, but they considered the mule to be at least three times more valuable in price than even a good chariot horse.

People of ancient Ethiopia gave the mule the highest status of all the animals.

Mules have been known in the Holy Land since about 1040 BC, the time of King David when the mule replaced the donkey as the royal beast, the “riding animal of princes.”

When the Israelites returned from their Babylonian captivity in 538 BC, they brought with them silver and gold and many animals—including at least 245 mules. Two Hebrew words referring to a mule or hinny are found 17 times in the Old Testament but there are no references in the New Testament—perhaps suggesting the popularity of the mule had declined in that region.

In October of 1785, a ship docked in Boston harbor carrying a gift from King Charles for George Washington—two fine jennies and a 4-year-old Spanish jack named, appropriately, Royal Gift. That “royal gift” from the Spanish king is today credited with the development of the American mule, which began a dynasty that “reshaped the very landscape of the country.”

The stud fee for serving horses was a third less than it was for serving donkeys. It is said that mules from Washington’s stock became the forerunners of mules that were the backbone of American agriculture for generations in the southern U.S.

By 1897, the number of mules had expanded to 2.2 million, worth $103 million. With the cotton boom, primarily in Texas, the number of mules grew to 4.1 million, worth $120 each. One-fourth of all the mules were in Texas and the stockyards at Ft. Worth became the world center for buying and selling mules.

In 1923, the U.S. Department of Agriculture issued Farmer’s Bulletin No. 1311, titled “Mule Production.” The publication explained the attributes of mules, and gave instructions on how to successfully breed good stock, as was learned in the 1800s.

It is quite clear to me that the mule is the most important four-legged animal for improving life for humans on the planet dating back to ancient times. The mule never gets any credit for that. The mule is the most interesting animal I have ever worked with because they don’t forget a single thing.

You can screw up training a horse and, with diligence, you can work that problem back out of the horse. You screw up with a mule and he will never forget and most likely take you back to that spot where he got the best of you. On the flip side, if you have the respect and trust of a mule, there is absolutely no better animal to partner with to get a job done.

Trust, respect, never seeking the glory and steady simple going about the business at hand to get the job done; those are the attributes of the mule. It appears to me that we have a president, 50 governors and nearly 330 million Americans that need to understand the role the mule has played to get us to this point in the journey. Those are admirable traits not only for mules but for humans, and especially leaders, as well.

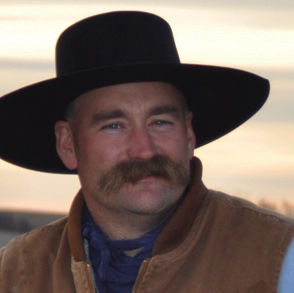

Editor’s note: Trent Loos is a sixth generation United States farmer, host of the daily radio show, Loos Tales, and founder of Faces of Agriculture, a non-profit organization putting the human element back into the production of food. Get more information at www.LoosTales.com, or email Trent at [email protected].