Unlike parts of Colorado and Kansas, Nebraska isn’t in danger of running out of groundwater from the High Plains Aquifer anytime soon. But the largest source of usable water in the state is still on average below pre-pumping water levels, according to the 2017 Nebraska Statewide Groundwater-Level Monitoring Report.

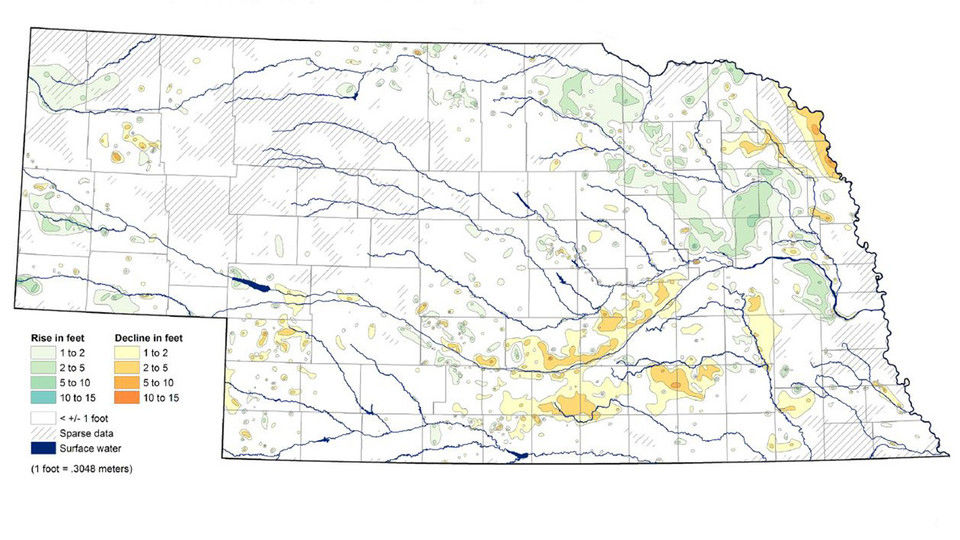

The recently released annual report examines groundwater level changes, including increases and decreases measured in regional wells in spring 2017. In addition to current levels, it also looks at historical trends, comparing regional water levels over extended periods of time.

The report is available for $7 from the Nebraska Maps and More Store, 3310 Holdrege Street and at http://marketplace.unl.edu/nemaps. Phone orders also are accepted at 402-472-3471 and a PDF of the report can be downloaded at https://go.unl.edu/groundwater.

“The reports coming out of Denver, Colorado, and Garden City, Kansas, are accurate for those regions, but they don’t accurately portray conditions in Nebraska,” said Aaron Young, survey geologist with the Conservation and Survey Division at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and lead author of the report.

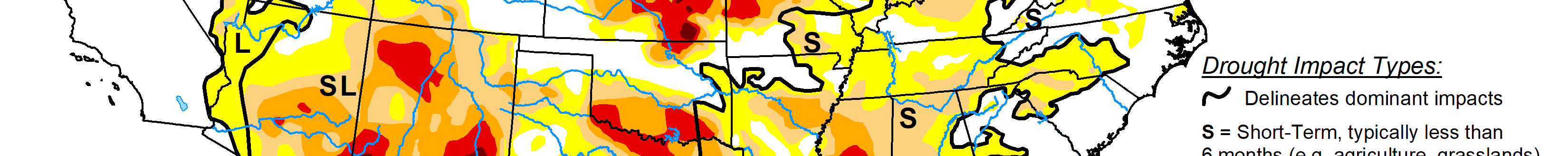

Nebraska has seen a slight decline in groundwater levels over the five-year period starting in the drought year 2012, with 71 percent of the 5,200 wells recorded showing water levels dropped by about 1.9 feet on average in that time period.

“From 2016 to 2017, groundwater levels in Nebraska haven’t really changed,” Young said. “Most of Nebraska received near-average precipitation, which reduced the need for supplemental irrigation, leading to little change in average water levels.”

About half of the wells in the state saw groundwater levels decline; the other half recorded increases from 2016 to 2017. Increases of 1 to 10 feet were recorded in northeast Nebraska, where above-average precipitation fell. Declines of 1 to 5 feet were recorded in areas along and to the south of the Platte River in south-central Nebraska, in correlation with below-average precipitation and increased irrigation pumping.

Problem areas in Chase, Box Butte, Perkins and Dundy counties in the far-west portion of the state continued to persist, due to irrigation use in regions with limited precipitation. Since about 1950, some of these counties have seen declines of up to 122 feet.

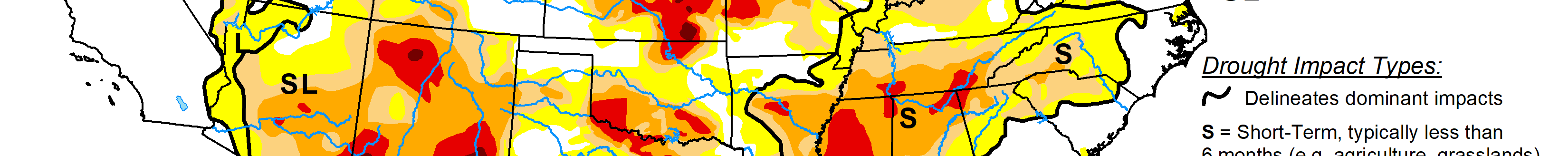

In-depth maps in the report give visual representations of these changes, conveying the information in one-year, five-year, 10-year and since-pre-irrigation (about 1950) increments. The maps are based on information collected by the Conservation and Survey Division, U.S. Geological Survey, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, Nebraska Natural Resources Districts and Central Nebraska Public Power and Irrigation District. The reports and maps have been produced by the Conservation and Survey Division since the 1950s. Groundwater monitoring began in Nebraska in the 1930s.

Other authors of this year’s report are Mark Burbach, environmental scientist; Leslie Howard, geographic information science and cartography manager; Michele Waszgis, research technician; Matt Joeckel, state geologist and CSD associate director; and Susan Lackey, research hydrogeologist.