The High Plains is known for its wheat production, and a monumental anniversary is being recognized in Kansas as Turkey Red winter wheat was introduced 150 years ago.

Russian Mennonite immigrants brought a hardy strain of wheat to central Kansas.

Allan Fritz, professor of wheat breeding at Kansas State University, said from a breeding standpoint, Turkey Red was a viable economic option for farmers who previously struggled with other crops—most notably spring wheat, which is commonly planted in northern states like North Dakota and Minnesota.

“In spring you need to plant ideally in the last half of February or maybe the beginning of March,” Fritz said. “You never knew what you’re going to get (with growing conditions). You might have snow on the ground. It might be too wet or too dry. There was a really narrow planting window, and then, if the crop needed to finish later, it was subjected more to the heat.”

A photo above courtesy of Glen Ediger shows vintage machines cutting wheat near Inman, Kansas, earlier this summer.

Early advantage

Turkey Red allowed for fall sowing, and a producer had a broader window for planting and that gave him more opportunity to have a successful crop when it came to harvest the following summer. If the crop matured earlier it was less likely to be stressed from the summer heat.

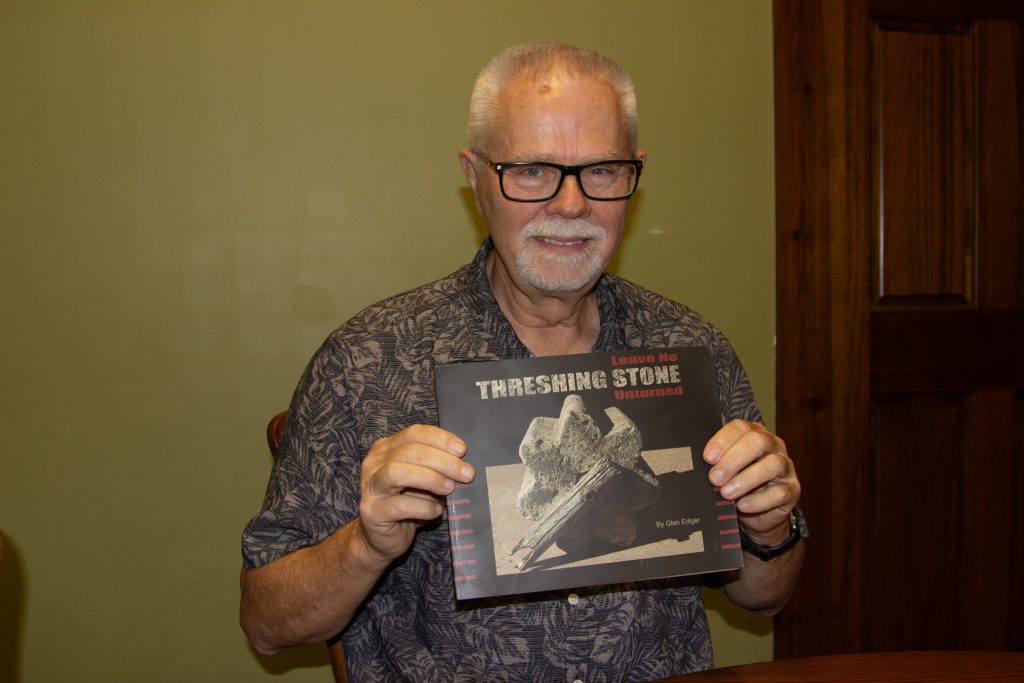

Glen Ediger of Newton, Kansas, author of the book “Leave No Threshing Stone Unturned,” said Turkey Red has ties to regions in the Middle East and Eastern Europe, most notably in Ukraine.

Much of the tracing from the Old World started about 500 years ago during the Protestant Reformation. Mennonites are often associated with the Anabaptist movement during the Protestant Reformation. Their start, Ediger said, was in Switzerland and the Netherlands. They faced persecution because of their beliefs, and they emigrated to other countries, including Prussia (modern-day Poland).

They eventually lost their rights under the government there, and in the mid 1700s Catherine the Great, who was German, provided them with a pathway to southern Russia (modern-day Ukraine). Faced with loss of rights again many years later some Mennonites immigrated to the United States, with the largest migration taking place around 1874. About 18,000 Mennonites moved to North America. About 8,000 located in Canada. Of the 10,000 who came to the United States, about 5,000 came to central Kansas, and the Santa Fe Railway was willing to sell the immigrants land.

While it was quite an undertaking to move across the world, Ediger said religious freedom and access to farmland was a compelling argument.

Farmer and miller

Bernhard Warkentin, a farmer and miller, was one of those influential Mennonites who brought the Turkey Red wheat from overseas, and Ediger said he brought to Kansas 10,000 bushels of wheat from the Ukraine region that helped farmers to get started farming winter wheat in Kansas.

“He was really a big promoter of Turkey Red,” Ediger said. “It takes a bushel to plant an acre of wheat.”

Ediger said Mennonites are associated with the success of winter wheat, but other immigrants with Catholic and Lutheran faiths settled in western Kansas, and they also deserve credit for pursuing their dream of freedom and innovation. In studying the Mennonites, Ediger said they were resourceful and, besides being good at raising wheat, they were also good at raising livestock. They understood how allowing livestock to graze on winter wheat in the winter and early spring could be an inexpensive feed source.

“It important to say the Mennonites were not exclusive in how they changed farming, but they had a great deal of influence then, and they still do today with their innovation on farming and livestock operations,” Ediger said.

Their innovative practices of years past included laying fields fallow in the summer, using livestock manure for fertilizer and rotating crops, he said.

‘Granddaddy of them all’

Wheat farmer Vance Ehmke of Healy, Kansas, called Turkey Red winter wheat “the granddaddy of them all.” Ehmke has grown Turkey Red, and he remembered it as a tall, spindly, low-yielding wheat variety that lodged easily and was susceptible to wheat streak mosaic virus.

It was also a variety that always had a very high protein content and unique kernel characteristics of being shorter and rounder than the varieties of today. Because of its high protein content, the kernels were always very dark red.

“While the variety got its toehold in central Kansas, it spread throughout the state within a short period of time,” Ehmke said.

“Up until then, Kansas farmers had been experimenting with a number of crops, but nothing seemed to work well,” he added. “Then, when this hard red winter wheat hit the fields, it was a natural fit, and its popularity spread rapidly.”

Game-changer wheat

Aaron Harries, vice president of research and operations with Kansas Wheat, said Turkey Red was a game-changer for farmers. In 1900, Kansas harvested 80 million bushels, but that had more than doubled to 172 million bushels by 1914.

It had a major impact on the state’s milling industry. Before the introduction of Turkey Red, milling had to be done with stone mills, and farmers and millers quickly realized they had to have better a process. That led to iron roller mills, Harries said.

Turkey Red was a harder wheat to mill, Harries said. Warkentin’s influence was important again.

Ediger noted that Warkentin’s mills were highly successful in Halstead and Newton by the mid-1880s. What Warkentin and other millers knew from their European experience was that the Turkey Red had a high gluten content and was the best for baking breads, Ediger said. As a result, he credits Warkentin for his vision.

Changes in flour mills

In 1900, Kansas had 350 flour mills, Harries said, and they were in nearly every small town. As Turkey Red became the norm, it led to greater efficiency, and that led to consolidation. Today, Kansas has about 10 millers, Harries said.

Turkey Red also changed the storage process. Before 1900, small wood elevators were the norm, but concrete silos became popular after that. Today, Kansas has a grain capacity of 1.6 billion bushels.

“Grain storage obviously predates Turkey Red, but it was mostly just small wooden elevators that were situated along railroads,” Harries said. “The explosion of wheat production in Kansas really accelerated that.”

Fritz said the early wheat breeders started with Turkey Red and landraces. The landraces were often developed in the area where wheat was native, and they looked for traits that had better disease resistance or traits sought in the region. The breeders then started to make selections and cross them to improve the quality of the wheat seed.

“If you trace back the pedigrees, you will find those traits as the foundation for virtually all of our varieties today,” Fritz said.

It all started with Turkey Red

Breeders continue to make improvements to meet the needs of farmers and millers, he said. Plants are shorter, but they have stronger straw, higher protein and better disease resistance. It all started with Turkey Red.

“If you think of it like building a house, the Turkey Red and those very similar landraces were really the foundation of hard red winter wheat,” Fritz said.

Harries said the introduction of semi-dwarf wheat by Nobel Prize winner Norman Borlaug was a major shift to the wheat we have today. Borlaug was an American agronomist who developed successive generations of wheat varieties with broad and stable disease resistance, broad adaption to growing conditions across many degrees of latitude and exceedingly high yield potential, according to the University of Purdue.

Modern wheat breeding has dramatically improved wheat yields while also shortening plant height, Ehmke said. Today’s varieties also have much improved disease resistance and standability. From what he has gleaned, virtually every hard red winter wheat variety grown today in Kansas can trace its roots back to Turkey Red. One of the early selections out of Turkey Red was Blackhull, a variety that was grown on the Ehmke family farm in Lane County in the 1930s.

“While Turkey Red has all but vanished from commercial wheat production, all of us Kansas wheat farmers owe a debt of thanks to the variety for providing a very firm foundation to the entire Kansas wheat industry,” Ehmke said.

Dave Bergmeier can be reached at 620-227-1822 or [email protected].

Future of wheat production

By Dave Bergmeier

Reversing a trend that has seen winter wheat acreage decline in the High Plains means adding value and rewarding growers, according to farmers and those who work with them.

Allan Fritz, professor of wheat breeding at Kansas State University, said the wheat industry is evolving, along with other commodity classes.

He expects more wheat to be bred for specific qualities that are useful for the baking industry or specific nutritional traits, such as certain amounts of zinc or gluten.

“It’s really important in order to make wheat have the value that it needs to stay up with acres,” he said, stressing the importance of crops that are adaptable to meet changing conditions.

To have success, breeders and farmers need wheat that can succeed despite drought or wet or extreme hot and cold weather so that millers can make flour and other products, he said. Additional research will continue from private and public entities, including the U.S. Department of Agriculture, he said.

The wheat breeder also suggested taking another look at the wild grasses that were the basis of the modern wheat crop in bringing diversity to modern varieties.

“Understanding the genetics, building the genetics and developing a variety to meet specific needs is the focus,” he said.

K-State was the recipient of a Global Food Systems Seed Grant award. Fritz and Dan O’Brien, an Extension grain economist, received $200,000 to increase wheat protein and gluten extraction to build long-term success for a Kansas-based industry.

“We can develop wheat that has value in the regard,” Fritz said. “Specialization of purpose is something we’ll see more of in the future.”

Dave Bergmeier can be reached at 620-227-1822 or [email protected].