Golden opportunities for GMO wheat on the horizon

For 20 years, genetically-modified wheat traits were set on the back burner, but now GMO wheat is back on the brain and the possibilities, as well as potential challenges, are abuzz. GMO wheat started making headlines once again after a drought-tolerant wheat trait was recently deregulated by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service.

The GMO trait—HB4—is derived from sunflowers. During drought conditions, HB4 produces more antioxidant and osmoprotectant molecules, which slow cellular breakdown and allow the plant to continue photosynthesis until it rains.

HB4 is a patented trait owned by BioCeres Crop Solutions in Argentina. It is the first GMO trait to be approved by both the Food and Drug Administration for human and animal consumption and by the USDA for cultivation in the United States. The U.S. is the fourth country to approve the use of this GMO trait after Argentina, Brazil and Paraguay.

“HB4 is a gene that modulates, or affects, the expression of several hundred other genes,” said Brad Erker, executive director of the Colorado Wheat Research Foundation. “This effect on expression results in increased tolerance to drought, a very complicated trait to breed for. Many wheat varieties have been naturally bred to be more resistant to drought, but this trait works on more of the cellular level to change how plants respond to water stress.”

The deregulation of HB4 is a milestone moment for the U.S. wheat industry, but it will be years before commercial varieties are released in the U.S. In the meantime, the trait faces significant barriers, such as integration into U.S. germplasm, consumer reception and export challenges.

Peter Laudeman, director of trade policy at U.S. Wheat Associates, said USW has been working diligently to support this advancement in biotechnology, but at the same time trying to handle its introduction in a responsible and stewarded manner.

Past GMO efforts

HB4 is not the first GMO wheat trait to be considered for deregulation. Monsanto developed a glyphosate-tolerant or Roundup-ready wheat variety in 1996, which started a revolution in agricultural biotechnology. The company tested the variety, known as MON 71800, between 1998 and 2005, but it was never brought forth for approval for commercial use.

Keith Kisling, a wheat grower and past president and secretary-treasurer of U.S. Wheat Associates, remembers meeting with 22 countries in the early 2000s to discuss glyphosate-tolerate wheat and gauge the acceptance of GMO wheat with foreign markets.

“At that time, Egypt was our biggest importer of our wheat, and their representative said, ‘You feed that GMO wheat to your kids for 10 years, and if they don’t grow an extra toe or finger, we’ll think about starting to import it. Until then, we’re not importing any GMO wheat.’”

At that time, there was no GMO wheat growing commercially in the world, and that meeting brought its progress in the U.S to a halt.

“I told them, if you release that, it’s going to cost us a third of our market,” Kisling said. “A third of our market would have been about a third of the price, and it would have taken a dollar a bushel off the price immediately, maybe more. There are so many countries in the world raising wheat, and it’s a dogfight to try to keep the customers you have. You don’t want to do anything to upset the apple cart.”

Kisling said he has reservations about HB4, but his concerns are more related to impacts on commodity markets. He fears an excessive production of wheat with the introduction of a drought-tolerant GMO trait that could drive the overall price of wheat down dramatically.

“I don’t want to starve people to death, and I know that sometimes there’s hardly enough wheat to feed the world, but I think it’ll have an effect on the price if we overproduce. However, I am for HB4 because it will give wheat breeders one more tool in their toolbox to improve wheat.”

High expectations

Although commodity groups, such as U.S. Wheat Associates and the National Association of Wheat Growers, have applauded the USDA’s decision to deregulate, not everyone is on the bandwagon just yet. Brett Carver, Oklahoma State University wheat breeder, wants to see the proof in studies conducted in the United States before he is convinced of HB4’s capabilities.

“There’s a lot of hype up front, but on the back end, there’s a lot of reality,” Carver said. “You want to bring those two things as close together as you can and get it figured out. My enthusiasm is a little bit tempered by common sense science.”

Carver has been breeding wheat for 39 years, and one thing he has learned over his career is that complex problems, like drought, usually require complex solutions.

“A single gene solution may remove some of the barriers, but it’s not going to remove them all,” Carver said. “That’s true for any trait, not just drought tolerance. It just needs to be adequately tested before we really build it up.”

Carver said he expects HB4 to produce superior results to what he can achieve conventionally.

“I’ve got to see more than a 10% yield bump,” he said.

Carver said he also wants assurance the HB4 trait will be highly adaptable to all drought periods and timings that are experienced in the High Plains. Finally, Carver wants a guarantee that introducing the HB4 trait will not interfere with other advancements in wheat improvement that have been developed over the last 50 years.

Consumer approval

GMO varieties of alfalfa, apples, canola, corn, cotton, eggplant, papaya, pineapple, potato, soybean, squash, sugar beet and sugarcane, are approved in the U.S. It is unclear how consumers will respond to the production of GMO wheat. GMO foods have been a stigmatized subject for years, and some consumers will still pay a premium for products labeled “non-GMO.”

Consumers often associate GMOs with health concerns, negative environmental impacts or believe them to be unnatural foods. Even though some of the general public has developed a phycological bias to GMOs, science has proven that GMOs are safe, with no adverse health effects and environmental benefits.

“There’s certainly a sensitivity level there, and I have to admit, I’ve taken advantage of,” Carver said. “The fact that we didn’t have GMO wheat actually helped calm some of the nerves with consumers. We almost had this unwritten social contract with them, and if we’re going to break that contract now, I want to break it over something that’s miraculous. I’m not yet quite ready to say this trait is miraculous, but I think there’s a possibility.”

Laudeman said he believes most consumers assume much of the wheat grown in the U.S. has been genetically modified for years, so adding it now would not affect their buying patterns. Argentina gathered data on consumer opinions when it surveyed Brazilian customers to see if they would be willing buy HB4 wheat.

“What they found was consumers had little to no preference, and there was almost a neutral impact once the trade actually started going,” Laudeman said. “When you look at the reality of the trade channels, there’s probably a lot less resistance than people would initially think.”

Trade concerns

Since pushback from export markets effectively dug the grave from glyphosate-tolerant wheat, the natural concern for HB4 varieties is whether foreign countries will import GMO wheat.

The U.S. exports about 50% of its wheat, and Laudeman said conversations with export markets like Mexico, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan will be a crucial piece in bringing GMO wheat to the U.S. Kisling believed this will be less of a hurdle for HB4 wheat because it is already being grown and consumed in Argentina and Brazil.

Erker said U.S. Wheat Associates and the National Association of Wheat Growers have adopted a set of principles for biotechnology commercialization, which they will use to responsibly bring a GMO trait into the marketplace.

“Within these principles, it is stated that regulatory approvals for food and feed use must be secured in major wheat export markets that represent at least 5% of the normal export volume,” Erker said. “There are seven countries that currently make up this list, and it will take significant work by BioCeres to achieve these regulatory approvals.”

Another obstacle with introducing GMO wheat is how to keep it stored and transported separately from non-GMO wheat.

“At the end of the day, U.S. Wheat is committed to is providing the type of wheat that customers want,” Laudeman said. “If that means that we create segregated GMO and non-GMO channels of wheat in the U.S., that’s something we’re absolutely looking into exploring and happy to work through an additional detail.”

Laudeman said Argentina has laid a lot of the groundwork for what a GMO and non-GMO wheat market could look like after introducing HB4 to consumers.

“Argentina started off segregating HB4 from the marketplace, but now it is totally operating on a bulk handling system, and they say it has gone perfectly fine,” Laudeman said. “It’s available all over the commercial marketplace in Argentina and has had little to no resistance at all.”

What’s next for HB4 and beyond?

Deregulation of HB4 was just the first step of a long and complex process that BioCeres has begun to bring its GMO trait to the U.S. Most experts agree it will be at least three to five years before any GMO varieties are commercially available in the U.S.—and that is only if there are no major obstacles that slow the proceedings.

Right now, HB4 has only been bred into South American germplasm, which is spring wheat. The next step for wheat breeders is to start experimenting by incorporating the trait into U.S. germplasm and hard red winter, soft red winter and soft white wheat varieties to see how it performs in North American environments.

“The trait needs to be bred into many diverse, adapted genetic backgrounds for it to be viable here,” Erker said. “Performance of the trait needs to be vetted in local yield trials to answer the question ‘Does it provide the advertised drought tolerance in our local conditions?’”

If everything goes as planned, the introduction of HB4 could be a game changer for the wheat industry.

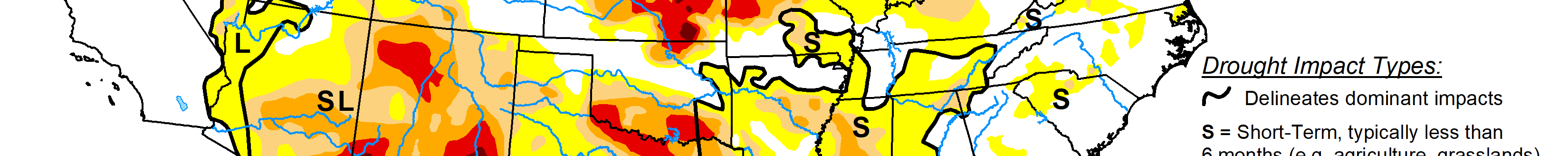

“When we look at every major wheat growing region having some impact from drought in recent years, it’s really a huge opportunity to be able to mitigate that factor in terms of consistent levels of production in the United States,” Laudeman said.

Most experts agree HB4 will be a test case for biotechnology as well as the marketplace when it comes to GMOs in wheat, and this trait could be just the beginning of what could be possible with wheat genetics.

“I think HB4 kind of opens the door for other GMO opportunities as well,” Laudeman said. “It could create a whole variety of disease resistance that can really be an enormous step toward consistency and production for wheat, not just in the United States, but really everywhere in the world.”

Erker agreed.

“GMO wheat can offer solutions to both producers and consumers that go beyond what traditional wheat breeding can offer,” Erker said. “HB4 has the possibility of delivering more drought tolerance than we’ve been able to achieve in other ways. Opening the door to GMO wheat gives us a chance to solve some of the great challenges for both producer-oriented and consumer-oriented traits that have eluded us for decades.”

Lacey Vilhauer can be reached at 620-227-1871 or [email protected].