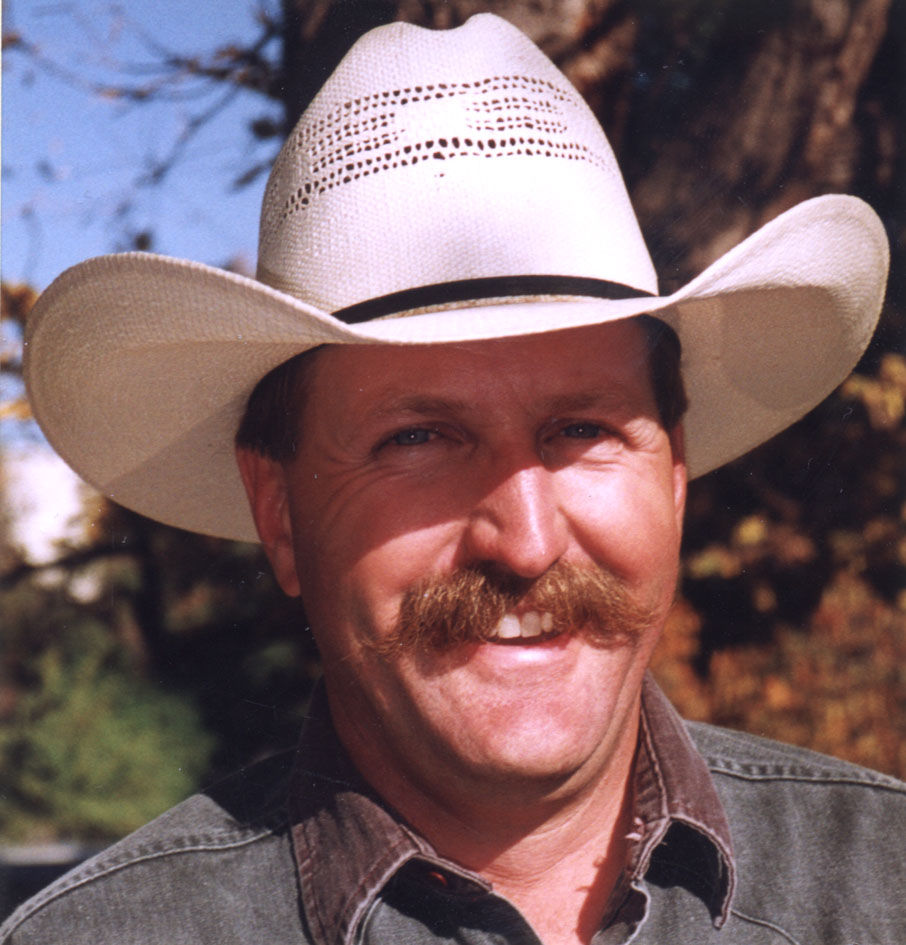

Kenny Rogers is one happy man, at least when it comes to the federal government.

The Wray, Colorado, farmer-feeder-Angus breeder is pretty happy and speaks the view of many in production agriculture, because 2017 marked the year federal agencies withdrew or delayed 1,579 planned regulatory actions, reflecting changes from fall 2016 to fall 2017.

Some of these were withdrawn during the administration of President Barack Obama while some were withdrawn during the administration of President Donald Trump. The U.S. Department of Agriculture saw 76 different Reports for Information—or RINs, for short—to amend, consolidate or eliminate regulations.

These RINs contained dozens of regulations, such as the 15 outdated regulations eliminated from the books of the Farm Service Agency, primarily related to long ended tobacco programs.

As arcane as some of the eliminated USDA regulations were, none were more welcome than the reversal of implementation of the interim final rule of the so-called “GIPSA Rule” that, under USDA’s Grain Inspection, Packers and Stockyards Administration, would have removed a burden of proof of harm requirement for a producer to be able to sue large corporations over alleged retaliation or anti-competition behavior.

In essence, the interim final rule was found by the Trump administration to conflict with case law in several U.S. Court of Appeals Circuits, which Congress has declined to overturn through legislation. Additionally, the interim final rule was improperly issued without adequate notice and opportunity for comment.

“There still is the means for a suit to be brought, it just maintains that it more or less must be proven, not alleged,” Rogers, a former president of the Colorado Cattlemen’s Association, said. “Personally, I’d rather the bar be kept somewhat high, still having the ability to pursue legally rather than basically drop it and let the trial lawyers have at it at any perceived injury. There are those who would have abused this with no end in sight.”

USDA has given regulatory relief in many areas. Yet, there were many regulations outside of USDA’s scope Rogers liked seeing eliminated in 2017.

The repeal of the Waters Of The United States rule brought by the Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and reverting back to its 2008 form tops his list.

“Efforts by various state and local cattlemen’s groups to offset and protect habitat were not being given proper consideration and may now play a bigger role,” Rogers said in a telephone interview. “Repeal of the disastrous WOTUS rule, which would have granted EPA broad overreach, brought in the Army Corps of Engineers and stripped us of any local control over the definition of ‘navigable waterways’.

“This was probably the biggest rules which would have essentially crippled traditional ag practices. So many implications and it would have been a never-ending story.”

Killing the proposed Bureau of Land Management 2.0 rule under the U.S. Department of Interior, was something Rogers also appreciated.

“BLM 2.0 usurped state and local land use decisions and restored that process to decision making back home,” Rogers said. “Ag has a long history of collaborative efforts with the BLM and I’m glad to see that repeal happen.”

Other rollbacks from Interior rules Rogers liked included the reduction in the scale of several national monuments and plans to reconsider protection policies for the sage grouse.

“The president also ordered a review of the addition of the previous 20 years of monument creation,” Rogers said. “This essentially reverts control back to state and local control of those areas. That’s a big win here for those affected, mainly us in the livestock business.

“Sage grouse policies were broadly considered to be a back door effort to remove or restrict grazing and oil and gas development. Efforts by various state and local cattlemen’s groups to offset and protect habitat were not being given proper consideration and may now play a bigger role.”

Agricultural labor issues are near top of mind for Rogers, but he’s waiting for Washington to act.

“Immigration reform? This is anybody’s guess,” Rogers said. “Trump has been trying to hand this hot potato to House and Senate for a legislative fix and so far they are running away from it. It’s anybody’s guess where this issue will ultimately end up. This is huge for agriculture, as we are the biggest users of labor out of this pool.”

Sign up for HPJ Insights

Our weekly newsletter delivers the latest news straight to your inbox including breaking news, our exclusive columns and much more.

Rules expanding the number of people who may receive overtime compensation also have been scaled back. Something Rogers appreciates.

“Ag is essentially a winner in this area as the seasonality of work is high in peak times, low in off times but averages out over a year’s time which allowed employers to be able to keep employees year round and not have to lay off and rehire,” Rogers said.

While deregulation was a good thing for Rogers, perhaps nothing topped the signing of a broad tax reduction bill. In particular, he was happy about the removal of the individual mandate from the Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare.

“It’s no secret that when the rule commonly known as Obamacare went into effect, many independent ag producers suddenly were faced with escalating health care costs,” Rogers said.

“Personally, in the past few years, our premiums have skyrocketed up to where they became unaffordable. Without disclosing exactly what those premiums are, I would say that for two people you could pay a pretty good year’s salary to a person for what those premiums would run. I’m currently seeking other alternatives and trying to stay off public assistance for health care. It’s probably the single biggest issue I had with the previous administration.”

Rogers said he’s seeing a net positive from these regulatory and legislative changes of the past year, yet he says he’s “really concerned with the rhetoric about trade.

“Ag is heavily reliant on our export markets, perhaps more than any other segment of our economy. Too often ag’s voice is overlooked because of the less than 2 percent of the population has any involvement in true ag production.

“It’s much easier for politicians to be concerned about steel, automobiles, or washing machines as they’re able to relate to them. When you start talking bushels, metric tons, pounds of beef, pork and lamb, it’s much harder for them to relate.”

If there’s anything Rogers is disappointed about this year, it’s the U.S. withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, as he thinks it would have opened up access for U.S. ag products to countries on the Pacific Rim where there currently is little to no export market.

“I realize that these agreements look at the package as a whole, but if they could have carved out beef, grains and other ag commodities, we would have gained quite a bit in those areas. Tariffs, quotas and other restrictions basically have the U.S. shut out,” Rogers said.

Rogers thinks deregulation worked in large part because so many farmers, ranchers and feeders were more tightly knit than past years to elect an administration and Congress united toward their interests.

“The average profit margin is razor thin as it is without government interference and with the independent nature of ag producers, much harder to put up an organized front,” Rogers said. “I’ve always said we (in ag) will circle the wagons, then shoot inward.”

Larry Dreiling can be reached at 785-628-1117 or [email protected].