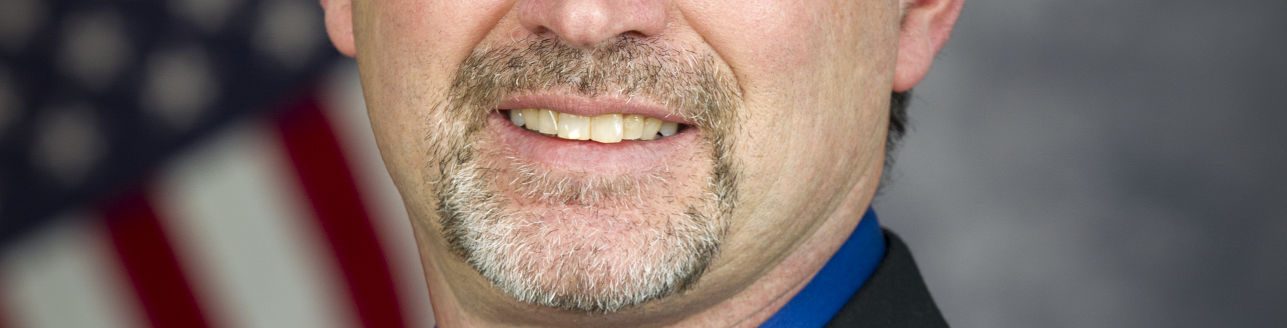

It’s a case that sticks with Kevin Buchanan.

A young nurse, once well respected and with a bright future ahead of her, charged with a felony for presenting false prescriptions for opioids to pharmacies.

“She was a fantastic nurse, but she had been injured in a car wreck and had been prescribed opioids for pain, and about four or five years later here I am prosecuting her for presenting false prescriptions to pharmacies,” said Buchanan, who is the district attorney for Washington and Nowata counties in north central Oklahoma. “We got her into treatment. But then she had a boyfriend sneak opioids to her while she was in treatment. She just wouldn’t—couldn’t—live without them. She lost her license. She lost everything.”

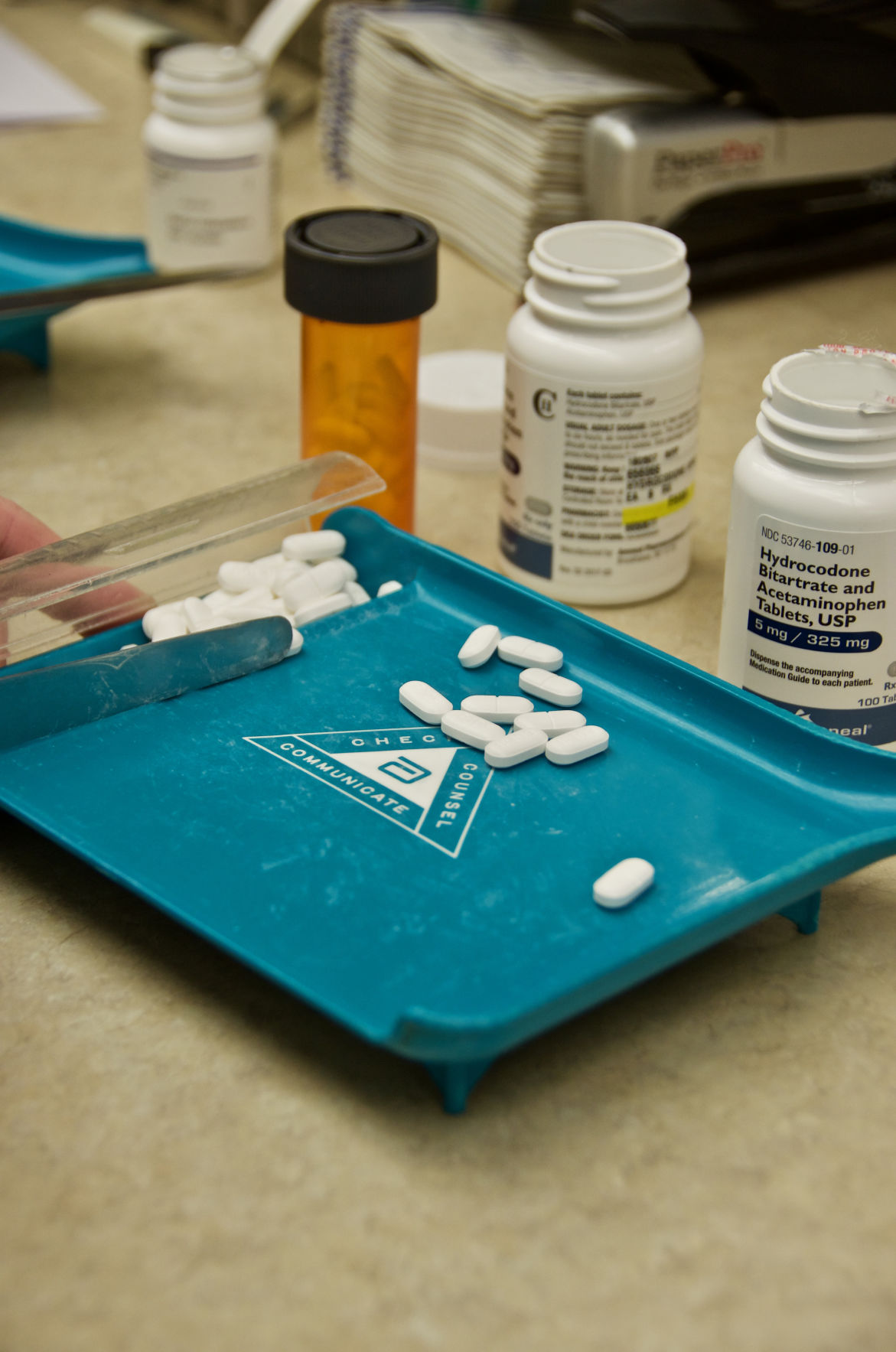

It’s a story that’s slowly becoming more common in communities big and small all over rural America. Opioids have been prescribed for nearly two decades, and addiction has silently grown in communities that don’t look like addiction zones.

But tallying it up is more than just dollars and cents. It’s neighbor’s lives. In places like Bartlesville, Oklahoma, and nearby Nowata County, which have significant oil and gas and agricultural industries.

“We have a lot of college-educated, white collar employees in Bartlesville, because of Conoco-Phillips,” he said. “And Nowata is very lightly populated, with a lot of agriculture, primarily cattle.” Most of the opioid problems he’s seen have to do with people getting injured and being prescribed a 30-day supply of pills to treat pain that could be managed with a 10-day supply of pills.

“So, now they have this 30-day supply to get through something like their wisdom teeth being pulled, and they get over the pain, but they then have these leftover pills,” he said. They aren’t trying to find these opioids to party with on a Friday night, he added. Instead, they’ve likely got a leftover amount from that legitimate prescription and they decide to use them later for recreation. Before they know it, they want more.

“What we’ve learned in these years of opioid prescriptions is that they are good to alleviate people’s pain, but that’s all they do,” he said. “Doctors were told early on that these were not highly addictive and we’ve found that’s completely false.”

In Oklahoma, the Senate created the Commission on Opioid Abuse, chaired by Oklahoma Attorney General Mike Hunter, bringing together members from the medical community, law enforcement, business and lawmakers to tackle this emerging crisis. Buchanan serves on the commission and said this effort is one way the state is trying to get out ahead of what communities in other parts of the United States are struggling with today.

“This is one of the few opportunities we have available, where we have seen such a pervasive problem on the East Coast, literally dozens of people dying in communities every day,” Buchanan said. “It was important for me, to head this off before it gets so bad that it’s such a big problem and hard to get our arms around it and fix it. It’s how we can try to avoid what looks like a plague there.”

The communities he serves are sadly familiar with what happens when drugs get a toehold in the region. Methamphetamine abuse is probably more prevalent today than opioid abuse, but having experienced the way methamphetamine can tear families apart, no one wants to wait and see what opioids can do to their towns and communities, Buchanan said.

“Hooked on methamphetamine or opioids, I don’t think the social consequences are any different,” he said. “People become unemployable as their addiction grows. They turn to theft in order to survive to the next fix. So you see a rise in theft, which starts generally as identity fraud, passing bad checks, stealing credit card information, that type of thing.

“Then, they start stealing from businesses to support themselves and their addiction.”

The cost to communities isn’t entirely in treating the addiction either. Just trying to find employees who can pass urine tests for drugs is a challenge, Buchanan added. And if they do manage to pass a test, depending on the depth of their addiction, life can revolve around getting their next drug dosage and the concerns about getting out of bed and making it to work on time fall to the wayside.

Many states are trying to get a handle on the costs of addiction before the crisis is out of control.

Every entity, every organization, has different data collection methods, and tracks different data points. Many of those are self-reported. That means someone has to be honest with a survey that asks if they have an addiction or are in treatment. Doctors must report that the deaths and injuries are directly related to opioids—and in many of those cases the true cause is a combination of the addiction to opioids and other health issues.

Unfortunately, those trying to get ahead of this crisis agree that it’s going to take more deaths and injuries to create the data that will drive the change in policy.

But a few states are trying to bring the opioid crisis to the courtroom in the hopes of at least making the manufacturers take responsibility for the costs incurred from addiction and overdoses by the state and local communities.

Terri Watkins, communications director for the Oklahoma Attorney General, said the most frustrating thing about the emerging opioid crisis is there just aren’t concrete numbers to the crisis yet. Tracking of overdose deaths, numbers of people in treatment, cost to businesses, non-violent and violent crime rates related to opioids and the emerging numbers of family court cases are all continuing to build.

It’s especially frustrating in places like Oklahoma that’s seen this all before with methamphetamine addictions. Community leaders can see that they’re at the cusp of a crisis and can foresee a larger problem coming in the future. While the state can see that there are hot spots on a map for addiction and overdoses, Watkins said, it’s going to take more data collection and research to drill down into figures. But the work is ongoing because these are people’s lives at stake.

“It’s almost impossible to find a right number,” Watkins said. “It’s so hard to get something specific on something that’s still an intangible.” Long term, the number that the attorney general’s office uses is “billions.”

“There’s the cost of addiction treatment, the costs of car accidents and work accidents, and drug-addicted babies and long-term health issues,” Watkins said. “The number we use is billions. It’s going to cost Oklahoma billions of dollars.”

“We really don’t have anywhere near the adequate resources now to treat the people who want to get off the drugs and it’s going to be a struggle,” Buchanan added. “Our entire criminal justice system is transforming from incarceration to treatment, but there are no new dollars for treatment facilities. We are decriminalizing theft and possession, but we have no new facilities and those left untreated are back on the streets.”

It’s a situation that will cost more than money in the long run. It’ll cost lives of more neighbors, like the once promising nurse who sticks out in Buchanan’s mind to this day.

Jennifer M. Latzke can be reached at 620-227-1807 or [email protected].