Shovel ready: Soil Health U offers opportunity to learn

Jimmy Emmons doesn’t leave home without a shovel.

He keeps one in every pickup and, on any given day, will stop by one of his fields to dig into the earth.

“I’m constantly looking to see where my soil is at,” the Leedey, Oklahoma, farmer said. That includes counting the numerous earthworms in his rich, carbon-filled soil.

But it wasn’t always that way. There was a time when he couldn’t find an earthworm. Soil and chemicals would run off fields after big rain events. The soil had been mined of nutrients and was badly degraded from four generations of tillage.

Change is never easy, said Emmons, who calls himself a recovering tillage addict. He has slipped a few times his past 25 years of no-till farming but hasn’t wavered from his soil health philosophy for more than a decade.

“I tell everyone a tillage tool sitting around is like a drug or alcohol,” he said. “You have to get rid of the temptation.

Emmons will tell his story during the High Plains Journal’s virtual Soil Health U conference in January. He and other soil health advocates will share their secrets, their struggles, the state of America’s soils, plus why farmers should consider regenerative agriculture amid a changing climate.

“It is really about changing the mindset and changing the focus,” said Kris Nichols, a soil microbiologist who is among the slate of speakers scheduled. “It is about focusing on the soil and regenerating the soil. That is the heart of it.”

Listening to Mother Nature

Regenerative agriculture has been gaining in popularity across farm country for the past several years.

Nichols, founder of KRIS, an acronym for Knowledge of Regeneration and Innovation in Soil Systems), said the goal is to build the soil back to the way it was before tillage. Among the principle’s foundation is the importance of having living roots growing as long as possible in the field.

She encourages farmers to focus not just on what they are doing above the ground, but what is happening below their feet.

For Indiana farmer Rick Clark, it took a weather event to get him thinking about the health of his soils.

The fifth-generation farmer had long followed in his ancestors’ footsteps. He would chisel the ground each fall then in spring, cultivating the ground twice.

“It was table-top smooth—nothing bigger than a golf ball,” he said. “Our farm was one of the worst tillers of the soil.”

However, Mother Nature had a different plan for Clark. About 15 years ago, when he was prepping a field for planting, he woke up in the morning after an inch of rain and couldn’t believe how much soil had run off into his ditches.

“That is what smacked me in the middle of the forehead,” he said. “It was time to change.”

Clark, who will also speak at the January event, continues to adopt regenerative agriculture practices to better the environment around him. Over the years, he began eliminating all chemical applications and is now transitioning his entire acreage to a no-till, organic operation that includes cover crops.

Keeping the ground covered throughout the entire year, along with crop rotations, is one of his secrets to achieving soil health, he said. His operation includes corn, soybean, wheat and alfalfa. He uses a different cocktail of cover crops in front of a specific cash crop.

Having a plan for the farm, plus timing is key, he said.

“The success of next year’s cash crop starts with the success of this year’s cover crop,” he said.

Another secret to success—yield doesn’t drive his system.

“Unfortunately, a farmer’s success is often measured by yield,” he said. “It’s not that I dislike yields, but yields aren’t running this farm. This is about reducing inputs and becoming much more profitable while at the same time you become a good steward.

“This is about how can we take more inputs away and achieve the same structure we have and increase profitability. I’m in the mindset I will sacrifice yield to maintain soil health."

Nichols hopes more farmers will change their focus from how to get the biggest yields or what they are told they can or can’t do on the farm. Also, she added, chemical and mechanical practices aren’t working as well as they once did.

It takes more synthetic fertilizer to produce a bushel of grain than it did in 1960, she said. Meanwhile, tillage only provides short-term results.

“You may get instant gratification, but, long-term, it becomes a greater investment,” Nichols said. “You have to keep using them over and over again to see those results you are looking for.”

Efficiency using regenerative agriculture, she said, will provide producers with more economic gain.

“Treating soils from a soil health perspective is the same way you would treat every other living organism and treat everything you are doing,” she said. “When you use tillage, you are essentially ripping off the limbs of other living organisms.”

That’s what some farmers have become disconnected from—an appreciation of their soil health.

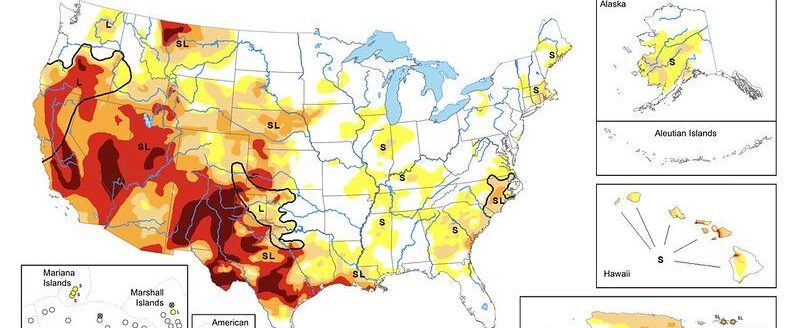

“The whole idea of Soil Health U is to take a look at your soil, take the shovel out,” she said. “Look at where you might see some gullies forming, where you might see some declines in production in some areas of your farm. Or, you aren’t responding to some of the climatic issues we are seeing—the drought periods and the heavy rainfall periods. Look at your farm and take in those observations.”

Seeing results

Clark applies no chemicals, synthetic fertilizers, insecticides or fungicides to his fields. Cover crops have helped him achieve balance in his system.

He said Erin Silva, a professor at the University of Wisconsin, taught him how to terminate rye without chemicals. For instance, he plants soybeans into standing cereal rye at boot stage then returns 40 days later when the soybeans are in the vegetative 2 or vegetative 3 growth stage with a roller-crimper.

“I roll everything flat to the ground,” he said. “Then, surprise, your soybeans will stand back up after you have rolled it. Dr. Silva showed me you can do this and start reducing chemicals. But I took it to the next level. I took the chemicals completely away.

“Now we have a system that is totally bound by the guidelines of Mother Nature."

Clark has been very pleased with his return on investment using this systematic approach. He is saving $828,000 a year on inputs compared to what he was using 15 years ago. Infiltration rates on his farm average 4 to 5 inches an hour.

“Change is good. You have to make up your mind that it is time to do something different," he said. "I’m not putting down anyone’s farming system. I’m just offering the possibility of another way of farming.

“If you aren’t uncomfortable with what you are doing, then you are not trying hard enough to change,” Clark said.

Meanwhile, Emmons, who once raised just wheat and cotton, now grows 14 crops on his land and runs a cow/calf operation on his fields yearlong to increase revenue from the land.

Emmons said he has cut chemical and fertilizer applications by 85% a year. Infiltration rates were just a half-inch an hour in 2010. Today, he can capture 8 to 10 inches an hour.

“We don’t have the runoff,” he said. “We don’t have the sediment in creeks and streams.”

Emmons, who will speak on the state of America’s soil during Soil Health U, also will tell listeners about the state of his own.

Earlier this year, when the Natural Resources Conservation Service visited the farm to do infiltration tests on his fields, they saw the results of Emmons’ hard work.

“They want to reclassify the first field I started converting into a soil health system from the original mapping,” he said. “The soil went from a light color, sandy loam-textured soil to a dark, rich soil with soil aggregates.”

Emmons admits he couldn’t believe the difference his efforts have made in such a short time.

“I think that is the real rubber hitting the road,” he said of the reclassification. “We know what we are doing is working, and that is exciting.”

Amy Bickel can be reached at [email protected].