Dave Dykstra, Siren, Wisconsin, has been ricing for more than 65 years. He learned his harvesting and finishing techniques from a member of the Ojibwe tribe who lived near Dykstra when he was growing up in Danbury, Wisconsin.

“There’ve been wars among the native American tribes for access to this resource,” Dykstra said. “The Chippewa and the Ojibwe chased the Lakota out of here to get the rice.”

The rice Dykstra is referring to isn’t the white rice or even the wild rice most people see in stores.

“That’s what we call paddy rice,” he said. “Wild rice is called Manoomin rice by the Chippewa tribe. That means good berry. It also means the food that grows on water.”

The Manoomin rice grows wild in lakes with moving water, meaning they are fed by rivers or springs. The wild rice in Dykstra’s area is a non-shattering rice. The seeds in the very top of the plant ripen first then seeds farther down ripen later on. Plants bearing wild rice can be harvested several times over the season and still produce because the seeds don’t ripen all at once. In shattering rice, on the other hand, the seeds all ripen at once and have to be harvested immediately.

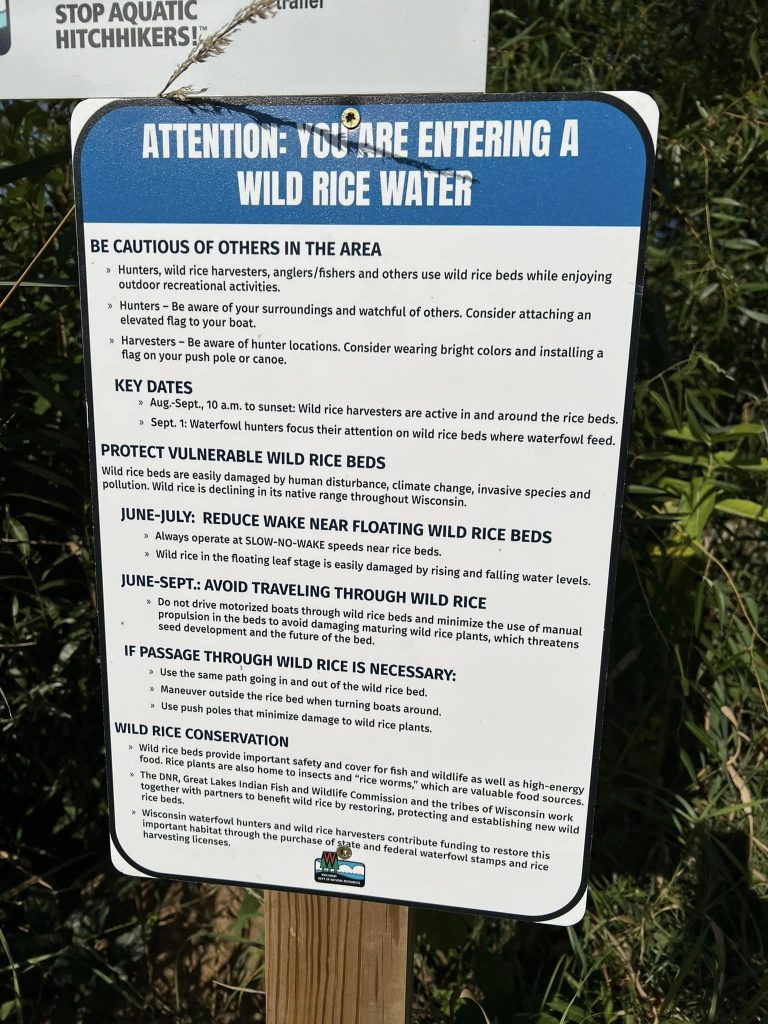

Harvesting wild rice requires a non-motorized boat—most often a canoe because it can float between the rice plants and a motorized boat would damage them—a pole to pull the canoe through the water, and a set of lightweight cedar sticks that are 36-inches long and tapered. The sticks are used to knock the seed from the plant into the canoe.

“Wild rice is not a grain, it’s basically a grass seed,” Dykstra said. “You bend the rice over the canoe, so the heads of the rice are in the canoe.”

As the seeds fall, those that miss the canoe land back in the lake lying dormant anywhere from two years on up to 10 years until the conditions are just right for the plant to germinate.

“One day you’ll have a lake with no rice and then soon it will be full of rice because the conditions were right and it reseeds itself,” he said.

Dykstra reuses small corn bags that typically hold about 30 pounds of rice. The amount can vary day to day depending on the condition of the rice. His record is 300 pounds in one day and his average over the years is around 50 pounds a day.

The journey of that rice doesn’t stop once it lands in the canoe. “I tend to finish it within 48 hours of harvesting in order to be stored for long periods of time,” Dykstra said, but first the seeds need to be dried so they can be separated from the hulls.

“We call it parching it. You used to put it into a big cast iron pot over a fire and stir the rice with a wooden paddle until it gets dry,” Dykstra said. “Then you would dig a pit in the ground and line it with deerskin and wear mocassins and basically dance on it.”

The dancing or swiveling motion would break the hull off the rice. It would then be thrown into the air to separate it physically, something Dykstra said was an itchy, dirty process.

He has used ingenuity to develop his own finishing tools and processes over the years. It still takes a lot of work and reduces the itchy and dirty part.

After finishing the rice can be frozen but Dykstra prefers storing it in air-tight containers.

“I think I’ve got some from 10 years ago that’s still edible,” he said.

Dykstra’s daughter Heidi Hertel, an accounting manager for High Plains Journal, started working with her dad in 2022 to learn the process of wild ricing and carry on the tradition. She said her favorite wild rice recipe is her mom Carol’s Wild Rice Soup. Dave seconded that and both of them mentioned wild rice hot dishes, or casseroles, as another favorite too. Carol was nice enough to share her recipes below.

At the height of his ricing days, Dave said his kids used to moan about having wild rice at yet another meal.

Sign up for HPJ Insights

Our weekly newsletter delivers the latest news straight to your inbox including breaking news, our exclusive columns and much more.

“Now they come home and ask me if I’ve got a couple bags,” he said.

Jennifer Theurer can be reached at 620-227-1805 or [email protected].

Wild Rice Soup

By Carol Dykstra

1/2 tsp salt

2 Tbsp butter

1 Tbsp onion

4 C chicken broth

2 C cooked wild rice

1/4 C flour

1 C Sherry, optional

Minced parsley or chives

1 C half & half

Melt butter in saucepan, sauté onion until mixture thickens slightly. Stir in rice and salt. Simmer about 5 minutes. Blend in the half & half and sherry.

Heat to serving temperature. Garnish with parsley or chives.

A Special Chicken Wild Rice Casserole

By Carol Dykstra

1 chicken, about 3 to 4 pounds

1 carrot peeled

3 tsp salt

1 large onion

1 stalk celery

Cook all until chicken is tender. Cool chicken and reserve the broth.

1 C raw wild rice, cooked

1/2 C light cream

1/2 C chopped onion

1 6 oz can mushrooms

1/2 C slivered almonds

1 small jar of diced pimentos

2 Tbsp chopped parsley

Cook the rice. Chop onion and pimento, drain mushrooms reserving liquid. Add enough broth from the chicken to mushroom liquid to make 11/2 cups.

Make white sauce out of butter, flour and onion. Gradually add broth mixture to this while heating over flame.

Add cream to the mixture and cook until thickened.

Remove from heat and add all ingredients together, stir thoroughly.

Put in large casserole dish and bake uncovered 30 minutes at 350 degrees.

This can be made ahead of time and put in fridge for a day before baking if you prefer.

This dish is time consuming but well worth the effort and is great when having company over for dinner.