Jim Mintert, agricultural economics professor at Purdue University, told attendees at the recent Kansas Commodity Classic in Salina, Kansas, to not hang their hat too heavily on projections and outlook forecasts.

No one could have predicted the war in Ukraine and its impact on grain markets. The same with drought and COVID.

“My point is it’s very difficult to forecast very far in the future,” he said. “And you have to be careful about having too much on a forecast. It’s impossible to do business without a perspective. Right?”

Mintert said the question those in agriculture need to ask themselves is how bad do you want to be better? How much emphasis do they place on strategic risk on their farm?

“Another way to think about it is the risk that maybe you really can’t forecast, right?” he said. “You can’t anticipate which one’s going to hit which time?”

Strategic risks often come from policy changes. For example, diesel fuel is regulated by the government and its policy is based on those regulations.

Changes in consumer preferences can change markets—take fluid milk for example.

“Consumers don’t seem to be drinking near as much fluid milk as they used to,” Mintert said. “We’ve seen some gyrations with respect to consumption of (these) products. We’ve seen some gyrations with respect to demand for meats, especially beef.”

Other risks are things like shifting weather patterns, technological advancements and other threats, must be realized and thought about beforehand, he said. A farmer has to ask is how they might impact his operation and assess that risk.

Resilience to risk can be thought about in two different ways.

“One is you have a firm’s ability to quickly identify and capture opportunities that are out there,” he said. “The other one is absorption capacity, which is the firm’s ability to withstand shock.”

During Mintert’s career, he’s been through a number of shocks has seen the impact from them. Embargoes, trade wars and the like.

“We were dependent on exports and all of a sudden the export pipeline was shut off,” he said. “There’s lots of things that you don’t really think are going to happen tomorrow. But they could. And the question is, what would that do to my farm?”

Assess yourself, too

Mintert challenged the audience to think about that and decide how agile your farm is or not and how it could absorb those kinds of risks. He tasked them to think about how advancements in technology, fluctuations in weather, uncertainty in international relations, changes in trade policies, and labor shortages play into farm operations.

“Think about how you would classify your farm’s managerial ability,” Mintert said. “Who’s the manager. Who’s got managerial ability? Most of your farms that have more than one principal involved?”

Assess whether or not you as an operator have the right skillset for that position. “If you don’t, what are you going to do to acquire the right to improve that farm?” he said. “Have you thought about and actually discussed your risk preferences? Does anybody actually do that?”

That along with risk preferences can lead operators down quite different paths.

“But the first thing to do is talk about it and find out what those differences might be, and how that might fit into your farms long term growth strategy.” Mintert said. “Every farm to be successful going forward has to have a growth strategy. If you’re gonna be around 20 years from now, you better have a growth strategy.”

And really, one last question he had—is your farm able to successfully operate and profitably incorporate new technology?

“I get lots of questions from industry about technology adoption,” Mintert said. “Which technologies do you chase. Which do you wait for? Which do you ignore? The challenges? Which ones are you going to do and how to actually adopt those and get those implemented on your farm?”

Longer-term trends

There are a couple trends Mintert sees affecting United States agriculture and farmer will likely see those continue. When it comes to the market share for world wheat and corn production, the numbers have change through the years. Around 1975, U.S. corn production was at 44%, and by 2023 that number had dipped to 32% or roughly a third of the world’s production, he said.

Wheat is even lower. Most recent data shows Russia having about 13% of the world wheat acres, while the U.S. is only at 7%. “Russia has become the largest wheat exporter in the world these days,” he said.

In the world corn acres, Brazil is seeing growth and in the 70s, they were seeing about 27 million acres in corn. The U.S. at that time was at about 68 million acres. By 2023, U.S. acres have climbed to about 87 million acres.

“They’re at 55 million acres. That increase Brazil has had these last roughly 15 years is huge in terms of the impact on the world market,” he said. “And truthfully, I don’t see that slowing down going forward.”

Ending stocks for soybeans are relatively low, and that’s causing concern.

“The problem is, every time USDA comes out with a report, they keep bumping up. That’s not a good thing,” he said. “The trend’s going the wrong way.”

By thinking longer term from a farm management perspective, a farmer doesn’t want to make all of his decisions focused on what’s happening in 2024, but instead looking ahead. For example, when evaluating the historical corn planted acreage numbers, USDA and the Food and Agricultural Policy Resources Institute at the University of Missouri, both think those acres are trending lower the next several years.

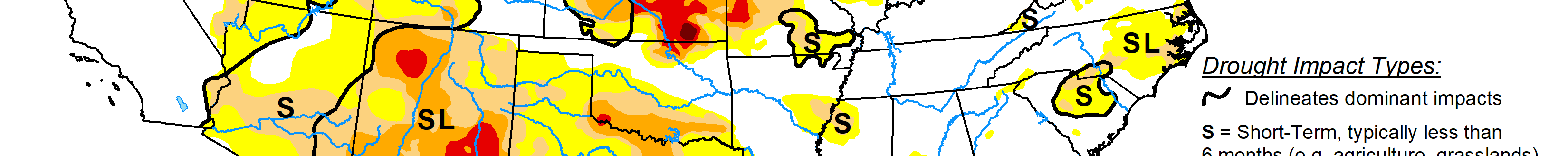

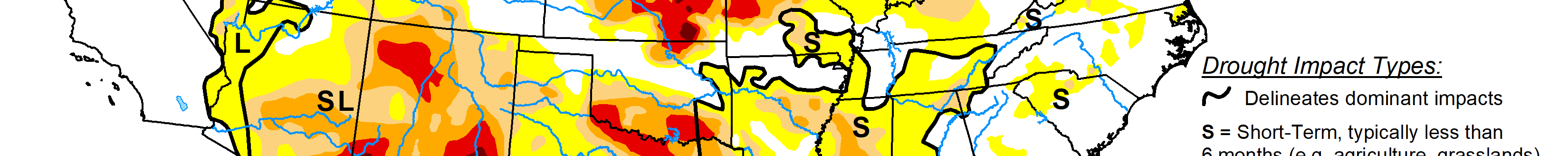

“Corn production—not too much change from where we’ve been recently no big explosion,” Mintert said. “And of course, whenever you do these long-range productions, projections, nobody forecasts drought right.”

He doesn’t see much growth in corn because of no real growth in ethanol—unless something happens in respect to sustainable aviation fuel. As far as corn prices go, both USDA and FAPRI are in line with one another.

Farm income projections are looking at income inflation rates adjusted going back to closer to the 10-year average.

“Probably looking at prices going back to those kinds of levels and the challenge is going to be where do we see these input cost?” Mintert said. “Big challenges if those are the prices, we’ve got to ratchet down the cost of raising corn and soybeans.”

USDA and FAPRI are anticipating a “big run up in soybean acres,” according to Mintert.

“You’ve all seen the arguments talking about we need more acres of soybeans to satisfy renewable fuel,” he said. “These projections suggest just like I told you, that’s not likely to happen here in the next couple of three years. Otherwise, we’d be looking at larger acreage.”

More beans aren’t getting crushed and there’s not been dramatic growth required to satisfy renewables with diesel.

Kylene Scott can be reached at 620- 227-1804 or [email protected].