“Out of sight, out of mind” is an expression often used to describe something that cannot be seen, so it is easily forgotten. On the subject of herd health, this phrase can easily be applied to our current approach to parasite management. Internal parasites—usually the size of the lead point on a pencil—are often ignored, underestimated and mismanaged.

These minute organisms have been feeding off their hosts since man first walked the Earth, and they are not going away any time soon. So, why do cattle producers continue to overlook their influence on herd health and their financial bottom line, while simultaneously building their resistance to the anthelmintic deworming products available?

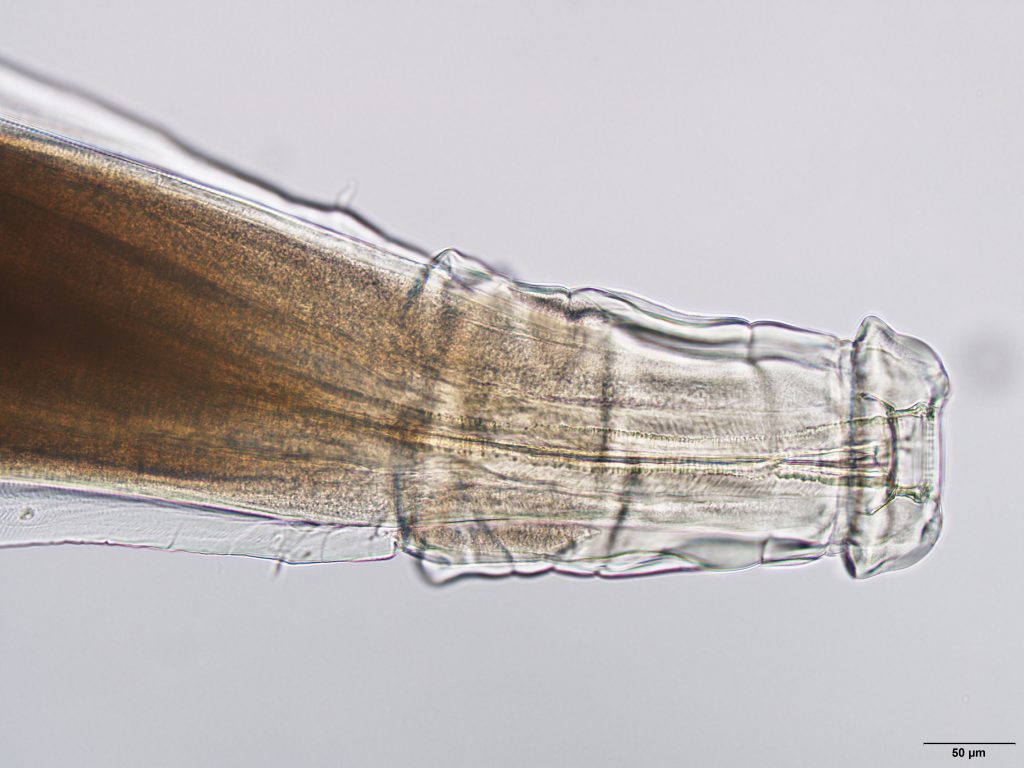

Dr. Rosslyn Biggs, DVM, is a beef cattle Extension specialist and director of continuing education at Oklahoma State University College of Veterinary Medicine. She said internal nematode-type parasites often found in cattle are not looked at as a holistic problem, which has led to multiple issues with worm loads and resistance.

“I think particularly when it comes to internal parasites, it’s not something that shouts out to us,” Biggs said. “Frankly, we have pretty good products that have made us comfortable. But it’s gotten us into some trouble when it comes to resistance. We’ve become content with not managing parasites in the best way.”

However, such tiny organisms can cause extreme damage internally with few initial signs.

“Until you have a major stressor, usually nutritional stress, that allows parasites to cause severe health or mortality problems, it’s not noticed,” said Dr. Christine Navarre, DVM, MS, DACVIM and Extension veterinarian at the Louisiana State University AgCenter. “They are costing us money from subclinical problems long before we recognize them.”

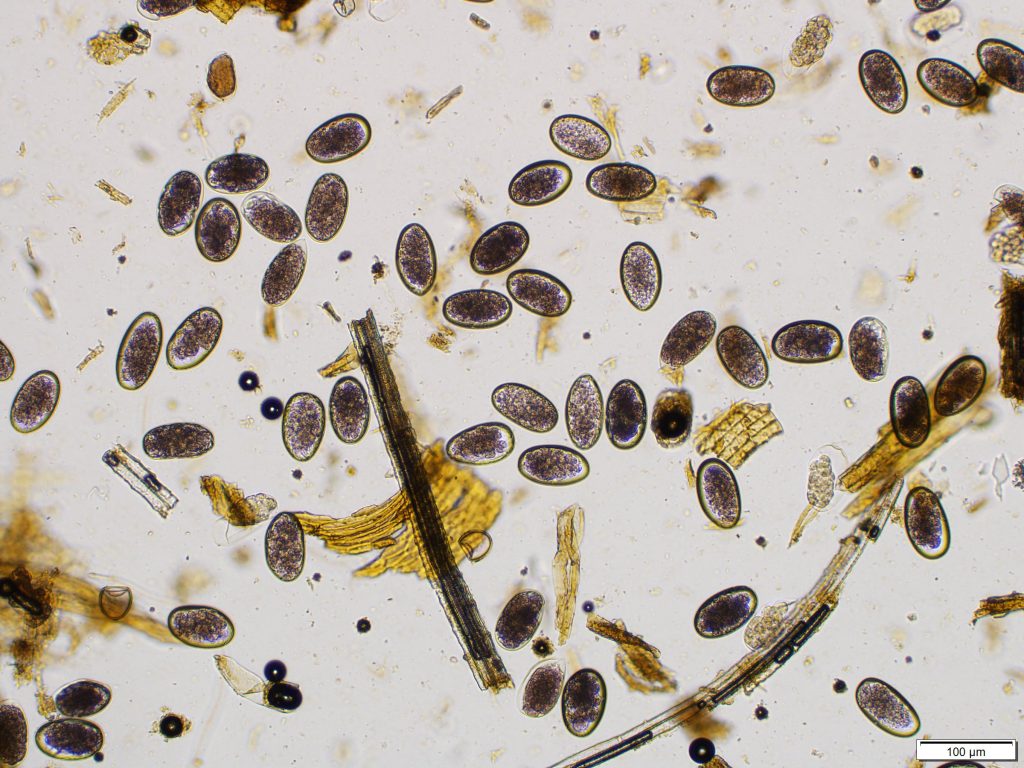

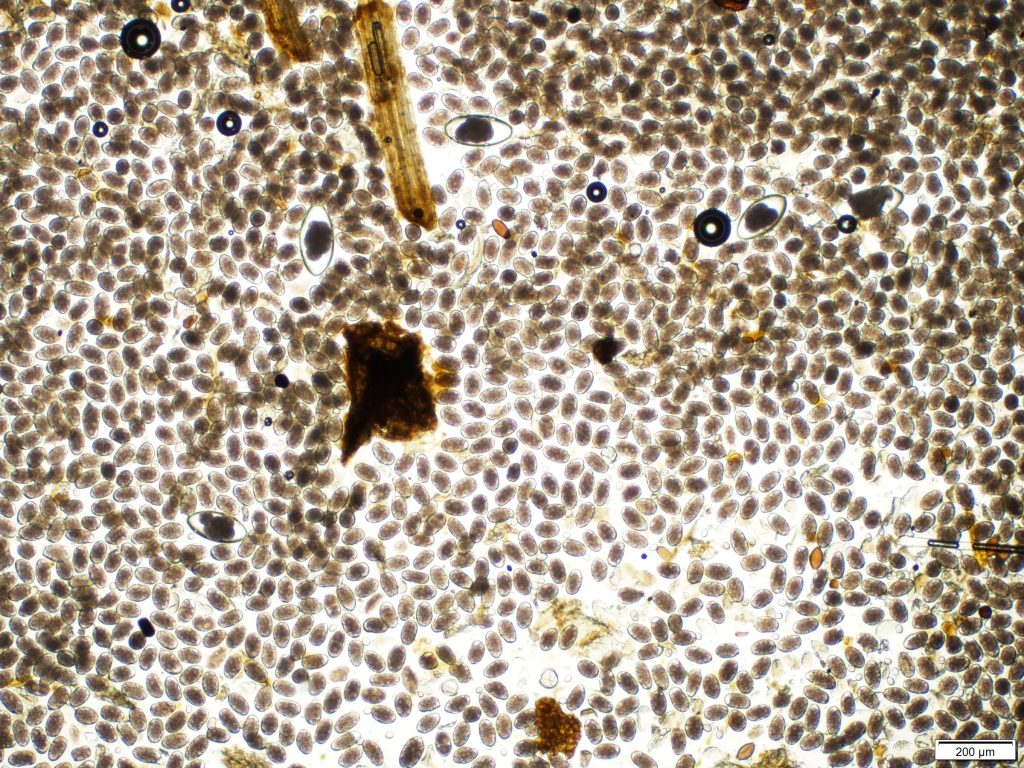

Biggs said animals have to be heavily parasitized for extreme symptoms to be evident. These include severe weight loss, poor coat condition, anemia or bottle jaw. Most of the time parasite-ridden animals are difficult to identify, but worms can still wreak havoc on an animal’s system and spread quickly through ingestion of eggs.

“We can really influence weight gain, particularly on young cattle, if we’re managing our parasites in an appropriate fashion,” Biggs said. “At the end of the day, most of us are marketing on weight when we go to sell those calves.”

Resistance and deworming mistakes

Parasite management is sometimes mishandled due to the labor associated with proper fecal egg counts and the costs associated with laboratory testing.

“Nobody likes to go pick up poop,” Biggs said. “One of the challenges with fecal egg count reduction testing is that you have to go back and sample cattle two weeks later. We’ve just kind of continued doing what we’ve always done, and that will likely lead us to greater development of resistance.”

Inadequate research on parasite resistance in beef cattle has also played a role in the current war on worms. Navarre said limitations in funding have led to limited knowledge of parasites. However, she said the beef industry must change its course.

“Anthelmintic resistance is out there, but not being recognized with proper diagnostics.” Navarre said. “I talk to veterinarians and Extension agents all over the country and Canada, and it’s everywhere. It will continue to get worse over time and come to a point where we don’t have any control over what happens. The sooner it’s recognized, the easier and less drastic the interventions need to be.”

The resistance parasites have developed is, in large part, due to how producers use dewormer. Biggs said one of the most common mistakes in parasite management is incorrectly dosing by the animal’s weight.

“Many producers, including myself, don’t have scales at our house,” Biggs explained. “Instead, we’re estimating weights and, in many cases, we underestimate what the weight of that animal actually is, and therefore we have the potential to underdose.”

Another common misstep Biggs identified is using the same class of drugs over and over.

“If you’re using an Avermectin product back to back, which would include anything with Ivermectin or Moxidectin in it, those are in the same class, and you’re not challenging those worms if you continue to do it over and over again,” she said. “Their job is to continue to survive, and they will figure it out.”

The application method is also important. Biggs said topical application of dewormer is much more convenient for producers, but quick, pasture “drive-by dewormings” are not always accurate.

“Topical applications aren’t dosed properly,” Biggs said. ”That goes back to not only weight, but the application itself. It can’t be all in one spot. It needs to have skin application in a broad way in order to absorb appropriately.”

Biggs said she prefers injectable and orally-administered products because she knows the medication gets in the cow.

Overstocking pastures is another common mistake that can lead to increased parasite load. Biggs said the higher the stocking rate, the more likely for conditions to be ideal for parasites to be transmitted from one group to another. Instead, use pasture rotations to keep animals from continually ingesting eggs.

Management techniques

Aside from administering dewormer products at the appropriate dose, cattle producers can also employ some other strategies to decrease resistance and reduce their need for parasite treatment.

“We need to evaluate each ranch situation, such as location, grazing, ages, ranch business model and goals, other stressors and health issues and diagnostics,” Navarre said. “Then we can come up with a plan that is specific to that ranch that balances minimizing resistance while maximizing health and performance. It takes some time and diagnostics initially but pays off in the long run.”

Biggs agreed and said having an appropriate parasite management program is important, but producers should also be cognizant of pharmaceutical stewardship.

“We only have so many classes of products available to us, and there has not been a new class available to us in a very long time. We want to use those correctly at the right doses and perhaps only on certain classes of cattle, making sure that the parasites are still susceptible to the dewormers we’re using.”

Biggs said the parasite load and susceptibility in a diverse group of cows, calves, bulls, heifers and steers is not always universal. Young cattle are usually the most vulnerable to parasite overload, and she recommends treating them primarily. For older cattle, Biggs advises producers to conduct fecal egg count tests when possible to determine if the worm load needs treatment. She said in some cases cows and bulls might not need annual treatment if their worm count is low.

“As they get older, there is typically some development of what we call innate resistance, meaning in the cow itself,” Biggs explained. “They become less susceptible, where the same number of parasites in a calf would do a lot more damage in that animal.”

OSU Internal Parasite Study seeks participants

By Lacey Vilhauer

Compared to other studies conducted on beef cattle, research on parasites and anthelmintic resistance are extremely limited. Dr. Rosslyn Biggs, DVM, said the few studies that have been done show resistance is becoming more and more of a problem.

The Oklahoma State University College of Veterinary Medicine conducted an Oklahoma-specific study recently, but it had limitations with a small number of beef cows being involved.

Biggs said results of that study led the OSU Extension team to ask more questions about the Oklahoma cow herd as a whole. It sparked the idea for a larger study conducted across the entire state with more animals in diverse categories, which is currently underway.

The larger study, called the OSU Internal Parasite Study, was launched in the summer of 2023 and is still in progress through the summer of 2024. Biggs said the research team is still accepting Oklahoma applicants who want to join the study.

There is not monetary payment for participation, but the laboratory testing of fecal samples is free and will be interpreted by a veterinarian. Those reports will be sent to producers, which will give them knowledge of their herd parasite loads. Extension personnel are also available to help collect fecal samples.

“They can make changes or discuss with their vet after getting the results,” Biggs said. “Ideally, we’re getting some answers for entire state, but also hopefully providing some value for individual herds.”

Biggs said this study has the potential to lead to more research outside of Oklahoma or to compare specific products’ effectiveness.

“Preliminary information from this study supports that we need to do more of this type of testing, and herd owners should take it under advisement and discuss fecal egg count reduction testing with their veterinarian to see if they are using the right product or if they even need to be deworming,” Biggs said.

To learn more about the study, scan the QR code or contact one of the study supervisors. These individuals include Biggs, at [email protected]; Dr. John Gilliam, DVM, at [email protected]; David Lalman at [email protected] or Paul Beck at [email protected].

Lacey Vilhauer can be reached at 620-227-1871 or [email protected].

However, as parasite resistance to available dewormers builds, so does the risk for all classes of cattle. Navarre said Ostertagia, a round worm commonly found in beef cattle, is developing resistance in older animals and young stock.

Producers should also consider if they are throwing away money on dewormer that is not necessary for the animal.

“We don’t want to waste money on products that may not be working on their particular ranch while at the same time negatively impacting the long-term health of the cattle,” Navarre said. “While there is resistance, we still have some efficacy in all products.”

Instead, both Navarre and Biggs said producers should be thinking about the concept of refugia. This means to leave certain animals untreated, which will in turn slow the progression of anthelmintic resistance in parasites.

“We want to make sure that we are managing our parasites so that we are leaving susceptible worm genetics in that population of worms,” Biggs explained. “Pasture rotations may be helpful in that approach. We may also want to consider when we’re wanting to maintain refugia in a herd, to maybe not deworm a certain percentage of that group of cattle.”

The microscopic parasites that populate pastures and live in our livestock can seem like a small problem, but an army of worms is nothing to underestimate. With proper use of medications and an adjustment in management tactics, the worms can be defeated.

“We have to do a total 180 on how we think about parasites,” Navarre said. “Change is no fun, and the control measures are very ranch-specific and take some time.”

Lacey Vilhauer can be reached at 620-227-1871 or [email protected].