Corn farmer remains optimistic despite hand he’s been dealt

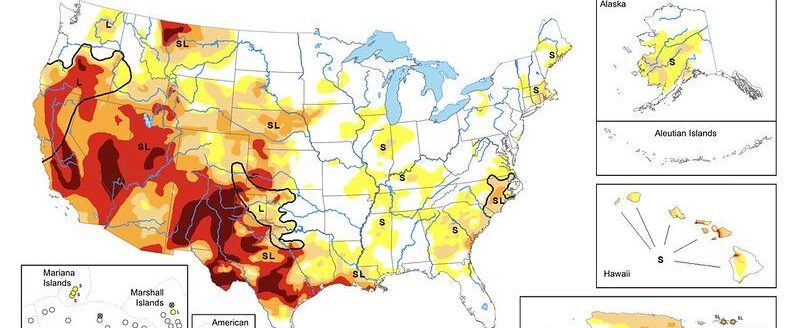

It’s roughly 50 miles from one end of Brent Rogers’ farm in Sheridan and Graham counties in northwest Kansas to the other, and in that distance, he’s experienced everything from good crops to hail and drought in the last few years.

Yet he remains optimistic. When interviewed in mid-May, his corn crop had mostly been planted. His irrigated soybeans were already up and growing.

Rogers raises irrigated corn, irrigated soybeans, dryland corn and dryland wheat. On the dryland acres he does a method of thirds—one-third corn, one-third wheat and one-third fallow. He also runs a cow-calf operation.

“All the irrigated land is stripped tilled, and the dry land is mostly 99% no-till,” he said. “We’ve started to till a few fields during the fallow period (to kill) what we call bunchgrass or pasture grass because we can’t kill it with anything but with a set of sweeps.”

Rogers’ farm was “pretty droughty” up until the middle of May 2023. Then he got anywhere from 20 to 24 inches of rain across the farm during May, June and July.

“I think we caught a little bit of rain the first part of August,” he said. “But with that came tons and tons of hail. We didn’t harvest 700 acres of our wheat because it was hailed out, and the majority of the rest of what we did harvest was hailed pretty bad.”

It wasn’t any better on the corn side. The irrigated corn even got hailed on the week of harvest.

“But yields were around 100 bushel, so less than half normal,” Rogers said. “And those particular areas became inundated with palmer amaranth because of the thinning of the canopy in the corn.”

Rogers is facing a tremendous amount of weed pressure this year because of all the weed seeds the palmer amaranth left behind in the hail storms.

“We’re gearing our chemical programs up to handle that,” he said. “One of the biggest concerns I have as far as challenges I face on my farm in the next five to 10 years is just running out of some chemistries that work well in all situations.”

Palmer amaranth is different to deal with, as spraying early in the year takes care of most of the problem with other weeds. Palmer amaranth keeps coming in August.

Rogers has also struggled implementing cover crops on his farm and hasn’t had much success because of the arid climate and they take up too much moisture and limit the ability to raise the next crop.

He’s had cover crops on some dryland acres for a few years. The first year, he added them during late spring with the intention of terminating them the first of June and fallowing those acres by chemical until the following fall. Then it would go back to wheat.

“We actually had good moisture, got it established and had a really good cover crop but then proceeded to hail about half of it before we terminated it,” he said. “We lost all the residue there.”

The wheat wouldn’t come up because the resulting soil was so dry. He decided to put cover crops behind his irrigated soybeans, trying rye and triticale. That worked in some instances, but not well enough.

“That’s had a little bit of success, but the problem with cover crops in northwest Kansas versus central or eastern Kansas or even the Corn Belt is you don’t harvest soybeans generally till the first of October,” he said. “By the time you get those harvested, if you get the drill in there the day after the combine leaves you might have stand up by the 10th or 15th of October.”

By then the warmer temps are waning, and there’s no growth to speak of. He’s tried seeding rye between the rows on some irrigated corn, but, again, timing wasn’t right.

“So it doesn’t start growing until you harvest the corn even if you pick the corn as wet corn,” he said. “You’re still late September, and there’s just not enough moisture in the climate to give you an established crop in the fall.”

Corn in the ground

“We’re over half done (planting),” he said. “I’ve been planting my soybeans first the last four years, one planter with soybeans, and the other planter plants corn.”

Rogers changed his soybean seed populations because of technology use.

“We used to drop an average of 180,000 seeds, and we are down to an average of 125,000,” he said. “Now that’s the average, so we’ve got some stuff in the 100,000s to 140,000 is kind of our range.”

Yield maps and sensory technology have allowed a reduction in the seeding rates. Rogers has been working with an Iowa-based company that writes all the programming instructions for him for his fields. Enhanced learning blocks in the fields work like seed trials.

“There are areas where the planter plants 100,000 seeds, and then there’ll be a strip next to that it’ll be 200,000, and then all we have to do is plant it and harvest, and we give them the yield data,” he said. “They go and analyze all that data, and they tell us on every field. They compile it into a printout or a summary basically that we have at the end of the season.”

He’s been doing this for three years and has been able to home in on where the “sweet spots” are with the seed population.

Down the road

Rogers’ wheat crop isn’t doing very well. It had a rough start when the rain stopped in August 2023, and it didn’t have much moisture to get going.

“Our wheat crop is pretty much miserable, if you want me to be honest with you,” he said.

The western part of the farm happened to catch some rain during mid-September, when a rogue storm went through.

“The wheat right through that area is going to be phenomenal considering the way the year’s been,” he said. “But we didn’t get any rain on the majority of our farm.”

One field is headed out now, and looks like it could make 50 or 60 bushels an acre. With another couple of hundred acres Rogers had “not a kernel that came up” until spring.

“So it’s going to be all over the board,” he said.

He started planting dryland corn in mid-May, and some timely rains helped the irrigated corn and soybeans without too much extra watering.

Rogers would like to be able to pull off an average crop, but he doesn’t see it happening unless there is “a ton of rain” this summer for the dryland corn crop.

“We’re going to have so little subsoil moisture and so low residue that if it gets hot and dry for a month we’re going to bake it right out of the ground,” he said.

He’s able to stay optimistic after the hail last summer and the lighter than average rainfall levels because of one thing: crop insurance.

“It doesn’t make you whole,” he said. “It isn’t like having a good crop, but it keeps it keeps you in business.”

Rogers said if he didn’t have crop insurance, he’d be done.

“I think that’s a pretty solid statement for most every farmer,” he said. “Does it dictate how I plant? Yes and no. I’m pretty fortunate. A lot of my dryland acres are crop shared still, so I don’t have to try to cover a cash rent payment on a lot of acres. That allows me to do that fallow rotation.”

Giving back

Rogers is the past president of the Kansas Corn Growers Association and remains on the KCGA board. He said he can’t stress enough how important it is for farmers to get involved in commodity and other organizations.

“We need more people to get involved,” he said. “The commodity groups are way, way more important than a lot of people realize.”

Until you’re involved in a group, or know someone who’s in one, Rogers said you have no idea what the work they do is and how influential it is.

“The voice that Kansas Corn has in Topeka and the voice that National Corn along with the states have in Washington is very, very important,” he said. “I don’t think a lot of people realize how much pull the commodity groups have with some of the institutions in Washington. Without that, our voice is not going to be heard.”

The crop insurance program is a prime example of this, he said.

“I don’t think there’s a bigger advocate of corn,” he said. “I’ve been to Washington DC four or five times, and that’s certainly been what I’ve always done to make sure that the crop insurance is as is and try to improve it and make sure make sure it’s here for everybody to use.”

Kylene Scott can be reached at 620-227-1804 or [email protected].

Irrigation technology helps bump efficiency

By Kylene Scott

Typically northwest Kansas, farmer Brett Rogers gets about 18 inches of rain annually, and with his irrigated acres, he’s been working to best use the water he has available. He has installed units that allow for telemetry on the pivots.

He described them as boxes at the end of the pivots with GPS systems that indicate that the pivot is on. Each one has a pressure gauge showing how much water is in the system. That allows controlling the speed of the pivot and indicates its direction.

This helps when Rogers wants to incorporate chemicals on the field. In the past, he put a flag at the end of the field and would estimate where it was set when the sprinkler was started, and then try to get it shut off at the correct time. Now he can shut systems off from the office or at home at night when the field has received an inch of water.

Rogers also credits the proper selection and updating of nozzle packages and the advent of drought guard seed and technology with helping to reduce costs.

Water probes that are buried in the fields and removed before harvest have also been helpful, especially when used with autonomous pivots.

“It is a ground-penetrating radar, and (it’s) used to measure soil moisture, basically,” he said. “So the beauty of that is, it travels with the pivot so you’re getting a reading around the entire field.”

Differences in soil types and elevation changes are accounted for, and it gives him more of a true reading across the entire field.

“The other beauty of it is it stays on your system,” he said. “So you don’t have to dig it up. ”

A rain gauge on the pivot helps by catching the actual rainfall on the field. A camera also captures images of the field.

“It’s taking pictures every 30 minutes off of the front of that tripod,” he said. “So you’re getting a picture that you can actually zoom in and see a ladybug on a corn leaf.”

Rogers has a few employees, and some of the irrigation technologies have helped them spend less time driving to the pivots.

“We can look in the morning and know right away whether a pivot’s shut off,” he said. “It sends us a text message as soon as they shut off, if they get stuck, if they don’t align.”

Employees can use a phone app to check the pivots.

“Some of those pivots don’t get visited but sometimes as little as once a week,” he said.