Soybeans have been a remarkable crop, able to flourish in domestic and international markets.

However, growers are rightfully taking note of disease pressure, and researchers know diseases wreak havoc on farmers’ bottom lines.

In Arkansas, soybeans are big business. Soybeans are Arkansas’s largest row crop, consistently ranking among the top 10 soybean-producing states in the nation, according to the state’s soybean association. In 2023, Arkansas farmers harvested nearly 3 million acres of soybeans, producing more than 159 million bushels, valued at more than $2 billion. The photo above is courtesy of AdobeStock.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture projects that Arkansas farmers will harvest 3.02 million acres of soybeans in 2024, with an estimated yield of 55 bushels per acre and resulting in more than 166 million bushels. As the state’s leading agricultural export, soybeans generated $1.3 billion in revenue in 2022.

Travis Faske, professor and Extension plant pathologist and director of the Lonoke Extension Center at the University of Arkansas, Division of Agriculture, said the diseases his growers see are both foliar and soil-borne. Foliar include septoria brown spot, frogeye leaf spot, target spot and Phomopsis seed decay. Soil-borne diseases include southern root-knot nematode, taproot decline and Photophthora root rot.

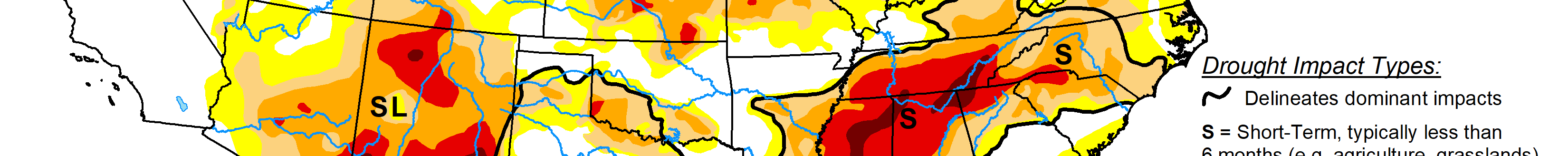

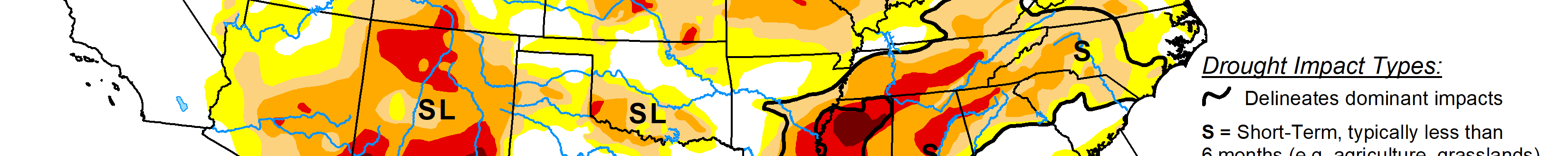

For the past few years, frogeye leaf spot reports have been low, but they picked up due to Hurricane Beryl. Plus, growers are likely planting more susceptible beans. Host plant resistance follows behind herbicide traits, he said.

“The southern root-knot nematode is our greatest yield limiting pathogen,” Faske said. “Each year we estimate about 4% loss statewide to this pathogen.”

With a limited number of cultivars, it has been a difficult disease to address. Taproot decline is also an increasing challenge because it does not have a good management tool like resistance in commercial cultivars, the researcher said.

Arkansas is not on an island, as Faske said other Mid-South states grapple with similar challenges.

Faske told High Plains Journal that growers are rightfully concerned about lower per-bushel prices, which in some cases are $4 to $5 a bushel lower than they were nearly three years ago. He said that puts a premium on limiting damage from diseases.

Faske believes seed quality is a must. “As with any soil-borne diseases, the genetics are the ball carrier, and we want to get the ball across the goal line.”

Foliar application can be at the mercy of Mother Nature, and herbicide resistance technology is expensive. Faske said resistance always falls behind technology. He said that focusing on quality seed that carries traits to address diseases is usually a good investment.

2025 tips

As growers look to 2025, Faske offered several tips.

“In fields with problematic diseases, select cultivars with resistance to that disease, especially the soil-borne ones, as there is little that can be done with them after the seed is planted,” he said, adding that growers can evaluate the past season to see what problems they encountered.

They should ask themselves what diseases were problematic in the past and what tools they need to mitigate losses from those diseases. They should take a nematode sample, preferably before Thanksgiving.

While most of Arkansas soybeans are under irrigation, in dry areas, root-knot nematode can limit grain production, and, in wet areas, those regions are prone to fungi that like water, most notably Phytophthora root rot and Pythium diseases. Nematodes are not only problematic in dry land production but also in irrigated fields. Because of that, yield losses are greater in irrigated fields.

“In these extreme situations, the greatest limiting factor is lack of or too much water, so diseases are probably not the only issue a farmer will face in those cases,” Faske said.

Familiar advice

He also offered sage advice that is familiar to long-time soybean producers.

“There are a lot of products out there that might claim a return on investment, but now is the time to research if those claims are true,” Faske said. “If something sounds too good to be true, it probably is.”

Research data is available at land-grant institutions and provides a valuable roadmap, he said. Growers get bombarded with advertisements about many products in the marketplace, but Faske said they should look to independent studies to confirm results. He said reputable seed companies will make their results from researchers available.

When applying fungicides, and there are many variables, it is best to protect yield potential when soybean plants reach the R3 and R4 growth stage.

“When it comes to grain production you’re trying to maximize profit,” he said.

He recommends for his growers to stop applying fungicides at the R6 growth stage.

Soybean cyst nematode

Gregory Tylka, director of the Iowa Soybean Research Center at Iowa State University, said soybean cyst nematode dates back to the early 19th century in Japan and was first identified in the United States in 1954.

SCN stunts the roots and shoots of soybeans and disrupts the functioning of the root system, which reduces yields.

What makes soybean cyst nematode such a troublemaker is it disrupts the effective uptake of water and nutrients in the plant. While it takes only about 30 days to complete its lifecycle, there can be four, five or even six SCN generations in a single growing season, he said.

“SCN numbers can build up very quickly because of the multiple generations in a single growing season,” Tylka said.

The pathogen often does not cause obvious symptoms above ground, so infestations exist for many years without being known and managed, he said. Some of the SCN eggs become dormant and can last 10 years or more, making it very long-lived in soils, and it can be spread by anything that moves soil, including in wind-blown soil.

Soybean cyst nematode is found in every soybean-producing state in the United States except West Virginia, he said. It is most damaging in the upper Midwest, where soybeans are often grown every other year in a field.

Management requires diligence. Tylka outlined three strategies.

• Growing SCN-resistant soybean varieties

• growing a nonhost crop, such as corn, after every year that soybeans are grown

• using nematode-protectant seed treatments when growing soybeans to possibly increase yields

Tylka said growers need to check by collecting soil samples.

“You can’t manage soybean cyst nematodes if you don’t know it is in your fields,” he said.

He suggested growers visit https://crops.extension.iastate.edu/blog/greg-tylka/fall-great-time-collect-soil-sampes-scn for details. Tylka also suggested growers visit TheSCNCoalition.com.

Contingency planning

Faske said, regardless of scenarios, growers need to have contingency plans. Weather remains the biggest variable growers face from season to season, even for those who have irrigation availability.

Harvesting on time, as closely as possible, helps to provide reliable results to evaluate, he said. He is a fan of crop rotation as a way not only to combat disease pressure but also to build soil health. Farmers know there are inoculants that can stay residually in the straw.

“You have to know the history of the field and know the risks,” he said.

When it comes to diseases, soil-borne ones are always going to be problematic with soybeans. In Arkansas, rice and cotton have been good rotational crops.

“As a plant pathologist, we use the word management and not the word control,” he said, adding that diseases often have infections and that they can lie dormant and wait.

Even during harvest and post-harvest, he recommends growers spend time scouting fields to get a jump on the next season.

Dave Bergmeier can be reached 620-227-1822 or [email protected].