The story of the biblical Old Testament’s Joseph, who I consider the first secretary of agriculture, highlights the timeless importance of grain storage during years of plenty to prepare for scarcity. Today, grain storage is still crucial for managing supply and stabilizing markets.

Grain storage is important to store, hold, market and distribute grain

Among the morass of reports released by the U.S. Department of Agriculture on Jan. 10 was the Grain Stocks report from the National Agricultural Statistics Service. In that report, NASS released the annual on-farm and off-farm grain storage capacity by state as of Dec. 1. As grain storage capability was important to Joseph, it is important for farmers, grain handlers and end users alike to store the harvested crop that is marketed and shipped for use throughout the marketing year.

Based on survey responses, NASS reported that grain storage capacity in the U.S. totaled 25.5 billion bushels as of Dec. 1, an increase of 0.1% from 2023. Over the past decade, grain storage capacity increased by 8.3%, but only 1.8% over the previous five years.

On-farm capacity totaled 13.6 billion bushels for 2024, an increase of 0.2% from 2023. Off-farm capacity was essentially unchanged from 2023 to 11.8 billion bushels in 2024. Over the past 10 years, grain storage capacity at off-farm locations has gained market share, increasing from 45.2% in 2015 to 46.5% in 2024.

High Plains grain storage capacity has been flat

High Plains grain storage capacity increased by 25 million bushels (0.2%) from Dec. 1, 2023, to 11.8 billion a year later.

Grain storage expanded 10 million bushels in both South Dakota and Texas. Capacity has been flat across the High Plains since 2019, when it totaled 11.75 billion bushels, a 0.3% increase over those five years, after steady expansion from 2004.

On-farm capacity totaled 5.9 billion bushels in 2024, which was up 0.4% from 2023. Off-farm capacity in 2024 was unchanged from 2023 at 5.88 billion bushels. Grain storage capacity across the High Plains by market position is shown in Figure 1.

In the High Plains, Iowa has the highest volume of storage with 3.6 billion bushels in 2024, where 57% of the volume was on-farm and 43% at off-farm locations. Nebraska had the second highest volume with 2.2 billion bushels followed by Kansas with 1.6 billion and South Dakota with 1.2 billion. Those four states had 73% of the grain storage capacity in the High Plains.

Grain storage capacity by state and market position as of Dec. 1 is shown in Figure 2.

Tepid High Plains grain and soybean production

In the Crop Production Annual Summary report also released on Jan. 10, NASS reported High Plains crop production for 2024 of 10.2 billion bushels, an increase of 6% from 2023. That production during 2024 was the second highest on record for the region. Despite being a much-improved harvest during 2024, production has been flat since 2014.

The area harvested has hovered close to 100 million acres, totaling 104.3 million in 2024, up from a recent low of 97.9 million in 2022.

With harvest area flat and production not expanding, crop yields are not trending higher. Corn yield averaged a record 176.3 bushels per acre across the High Plains in 2024, while averaging 170 bushels since 2015.

High Plains crop area and production by crop are shown in Figure 3.

High Plains grain storage capacity is highly under-utilized with limited incentive to expand capacity

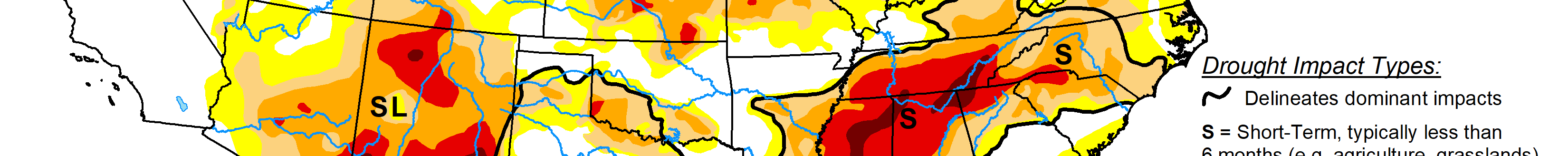

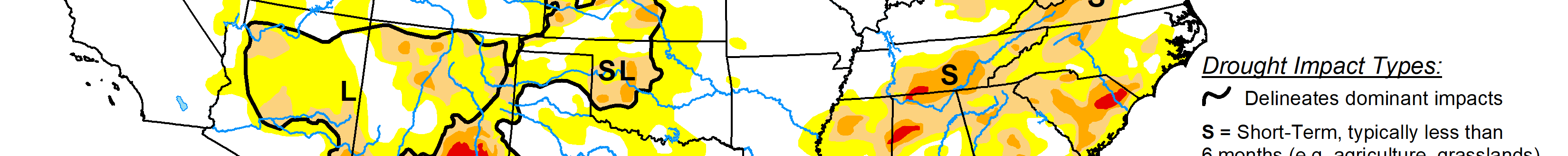

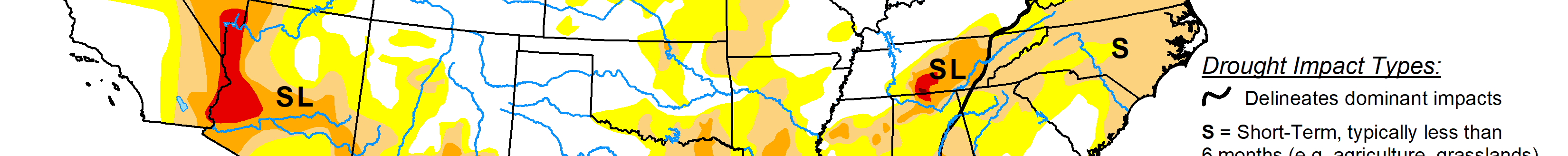

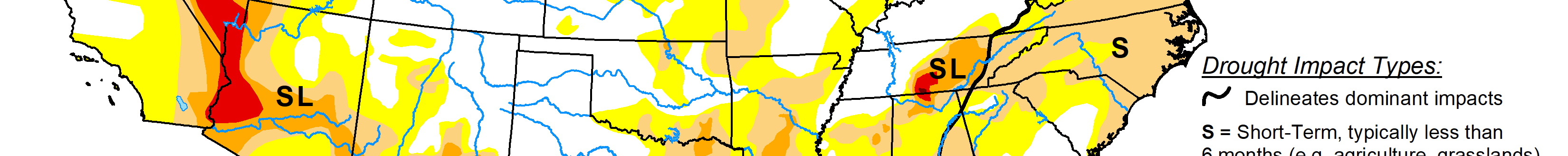

The fact that grain production across the High Plains is flat with a lack of yield growth potential does not bode well for grain storage to expand. With steady storage expansion from the early 2000s and peaking around 2018, capacity has outpaced crop production. As a result, storage capacity utilization is slack as shown in Figure 4.

To make matters worse, grain prices are low, causing farmers and off-farm grain handlers to pause their decision to invest in more storage capacity. The cost of building storage is still expensive, adding insult to misery. For example, cement and concrete prices continue to increase, with the purchase price index in December at 248.7, up 4.1% from the previous December.

Steel pipe and tube, stainless steel prices have been trending lower, posting a PPI of 133.3 during December 2024, down 4.4% from the previous December. However, steel prices are still higher than they were during late 2021. Cement and stainless-steel prices are shown in Figure 5.

Grain storage capacity is an important tool for farmers and commercial operators to hold and handle crop harvest. From that storage, grain is marketed during the crop marketing year until the next harvest.

But with grain production stagnant across the High Plains, storage being abundant and the cost to build new storage still elevated in a low grain and soybean price environment, there is no incentive to expand storage across the High Plains.

Ken Eriksen can be reached at [email protected].