Sharing the roads safely with farm equipment important every day, not just during harvest

Vehicles traveling on public roadways need to be conspicuous. The more they stand out, the less chance there will be for a collision, one expert said.

John Shutske, a professor in the department of biological systems engineering at the University of Wisconsin Madison, and Extension agricultural safety and health specialist, spoke during a recent webinar during National Farm Safety and Health Week.

Shutske’s research has tackled issues of respiratory hazards, dairy worker risk around antibiotic resistance and stress suicide prevention in farming communities. During the webinar his focus was on rural driving and public roadways. There are several considerations when driving in rural areas.

The farm population is aging, and Shutske believes that impacts farm safety, farming injuries and driving on public roadways.

“The age difference between the agricultural industry and the general worker population, it’s about a 20-year difference,” he said.

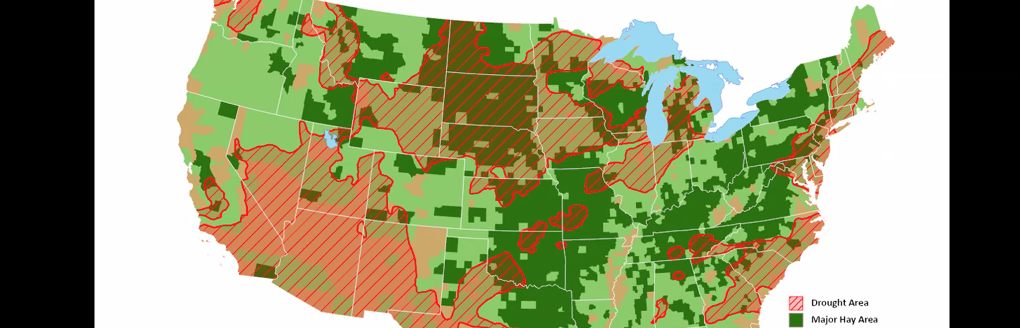

Plus, farm operations are growing in size in terms of crops acres and the number and size of animal herds.

That necessitates people having to travel longer distances, often on public roadways, to get to their land or operation. Shutske and his father farmed on 900 acres and travel between properties took time, he said.

“We farmed with really small equipment, and he farmed in three different counties,” he said. “We typically didn’t trailer anything. So, we drove. We spent a lot of time on the highway.”

Traveling speeds

The speed difference between a car or truck versus a tractor is important.

“If you think about that, being at a speed of 60 miles per hour versus a tractor at 20 miles per hour, typically spending just hours and hours on the roadway every single planting season and every single harvest season,” he said. “And just like a lot of parts of the country, we are seeing big growth in the urban and suburban areas.”

Collisions with farm equipment are becoming more common and Shutske helped summarize 2017-2020 data with the National Farm Medicine Center, and what was found is about a quarter of the fatalities that involved some aspect of the farm workplace, including machinery on highways—were because of collisions.

Another study Shutske cited noted farm labor transportation and non-labor farming vehicles on the highway reported the rate of fatality on a crash per crash basis is significantly higher with farm machinery, as you might expect.

The speed and weight of vehicles are important, he said. All those add into an opportunity to dive into the subject from multiple perspectives.

Fall day scenario

Shutske said picture a rural public roadway, possibly a two-lane highway, and maybe a driver is in a no-passing zone and approaching the back of a tractor pulling two gravity flow wagons full of corn or wheat. The weight of the tractor, wagons and the commodity contained in them starts to exceed 50,000 pounds depending on size. Perfect conditions—flat roadway, decent lighting, no glare, pavement in perfect condition—are ahead for the driver who’s going about 55 mph.

“We’re going to probably see that grain train out ahead of us—that tractor, two wagons, is about 600 feet of distance,” he said.

After some calculations, Shutske said the driver is traveling about 80.7 feet per second. On the other hand, the tractor and wagons are going in the same direction at 18 mph.

“So, if we do that same math—we’re traveling at a speed, a forward velocity of 20.4 feet per second, and the fact that they’re both moving in the same direction means we need to subtract the wagon speed from the car speed,” he said. “The SUV is approaching the back of that 27-ton train at a relative speed of 54.3 feet per second.”

In an ideal situation, it takes about 600 feet of distance which a vehicle needs to stop or about 11 seconds.

“We have 11 seconds to figure out what’s going on up ahead of us, get slowed down, or if we need to stop, actually get stopped in time,” Shutske said. “Think about this in an ideal situation. Now the question is, but do I really have 11 seconds? Actually, the answer is no, I don’t have 11 full seconds to get everything slowed down.”

If the conditions are less than perfect, it takes even more time to slow down. It could be foggy, low light conditions, evening conditions or even a light rain or moisture left on the roadway because of morning dew.

“Not only is your visibility going to significantly crunch down that distance, that braking distance and that reaction distance, but the other thing that’s going to happen, it’s going to take me much longer to slow down,” he said. “Or instead of approaching something that is traveling in the same direction as I am at 18 miles per hour that vehicle has decided it’s going to make a left-hand turn, maybe at the same time that I’m choosing to pass on the left.”

Essentially a driver would be approaching a brick wall at 55 mph.

“And that’s when we see these terrible, horrible collisions that happen,” Shutske said.

Shutske said “so much of” highway motor vehicle design is based on making vehicles conspicuous or to recognize for an oncoming motorist in order to take appropriate action.

Hierarchy of controls

He also discussed hierarchy of controls that notes many types of farming injuries and exposures, which means there are multiple ways to approach prevention.

First, work to eliminate the opportunity for both types of vehicles—passenger vehicles versus farm equipment—to be on the highway at the same time. For example, Shutske said on federal highways it’s not legal at least in most parts of the country to drive “that 27-ton train moving 18 mph” on a federal interstate highway.

“But in most parts of the country, that’s pretty impractical, and obviously politically, it would probably not be feasible, but it is possible to eliminate this potential for collisions,” he said.

Instead Shutske suggests trailering equipment or instead of using gravity wagons to move grain, use a larger vessel so less trips can be made. He also suggested changing the time-of-day travel. Instead of going first thing in the morning while others are going to school or work, wait until people get to where they need to be in the morning, as an example from 6 to 10 a.m. The same strategy applies in the evening.

Properly marked

Shutske also recommended making sure the equipment is properly marked. Slow moving vehicle signs need to be designed according to engineering standards.

“I can go out and buy a really cheap SMV emblem off of Amazon, and it may not last more than like 36 months, but the newer ones are designed with a much longer life,” he said. “The other one that I want to just highlight for you is the retro-reflective material. Retro-reflective tape is a relatively new development in the last 20 years or so. Essentially, what we’re talking about is prisms or mirrors that will directly reflect light back that is shined upon this SVM.”

“Standards are really crucial,” Shutske said.

Headlights and taillights are what he calls “baseline obvious.”

“You want visibility to the front. You want to be seen from the back side, also flashing amber lights,” he said. “But critically important is the fact that these flashing amber lights also be able to double as turn indicators.”

Reflectors marking the extremities of outer edges of equipment is necessary too.

“Whether we’re talking about the toolbar on a piece of tillage equipment or the width of a wagon,” he said. “And then the other intervention that is connected to the slow-moving vehicle emblem is the retro-reflective tape.”

That includes marking the outer edges of the equipment.

Newer, more modern machines and equipment have a very good, high level of protection, according to Shutske or “at least a way of dramatically reducing the risk” through lighting and marking.

“I see lots of opportunities for farmers to add flashers that could double as turn signals and turn indicators,” he said.

For more information about farm safety visit https://www.necasag.org/nationalfarmsafetyandhealthweek/.

Kylene Scott can be reached at 620-227-1804 or [email protected].