Inside the Friday afternoon class where Texas A&M freshmen learn brisket, mentorship and belonging

It’s 4 p.m. on a warm Friday, and West Campus is quiet. Parking lots sit half empty, hallways are still and classrooms are dark.

Inside the Rosenthal Meat Science Center, however, a very different scene comes to life. About 75 freshmen flock to the building, most arriving at least a half hour before class is scheduled to begin. Lively chatter fills the room as students trade stories and greet the professors who will teach them to tend to a barbecue pit and a community.

Each year, incoming students in the Texas A&M College of Agriculture and Life Sciences aim for a spot in Texas Barbecue. Why all the fuss over a late Friday afternoon class?

Ask the hundreds who have spent a Friday evening in ANSC 117. Texas Barbecue has earned its following because it builds lifelong ties and fosters a people-first culture.

“Texas Barbecue is a class like no other,” Clay Mathis, Ph.D., professor and Department of Animal Science head said. “In a university so massive, these students are able to find a tight-knit community in the Department of Animal Science that will help carry them through their college career.”

“People have met their best friends, bridesmaids, groomsmen and even spouses in this class,” said , vice chancellor and dean for Agriculture and Life Sciences. “There’s a wide circle of people who have become a community because of Texas Barbecue, and that’s something special.”

A culture like this took years to grow. In fact, the roots of Texas Barbecue can be traced back to a friendship founded decades ago – a friendship that set the tone for everything that followed.

The brotherhood behind the barbecue

Savell and Ray Riley ’79, retired manager of the Rosenthal Meat Science Center, grew up together in Ferris. Davey Griffin ’78, Ph.D., AgriLife Extension meat specialist and professor in the Department of Animal Science, joined the pair at Texas A&M University in the mid-70s.

Riley and Griffin were undergraduates and Savell in graduate school, but their bond only strengthened as careers, marriages and children came along.

“Think about the miles we’ve traveled together,” Riley said as Savell and Griffin nodded. “We’ve stood by each other’s sides through kids’ weddings, parents’ funerals, emergency room visits and a whole lot of life. That’s what it’s all about.”

The trio is well known in the meat science field. Students, coworkers and friends refer to them as “The Three Brisketeers,” a nickname earned through years of teaching, research and outreach.

“People come to us in the barbecue world because they trust our educational approach, hard work behind the scenes and overall knowledge of meat science,” Riley said. “We’ve worked with packers, retailers and a variety of different programs and camps.”

Their love for the barbecue industry is evident. Talk to any of them about this Texas cultural staple and you’ll notice an immediate spark in their eyes and lilt in their voices as they recount stories of road trips together and hours spent out by the pit or in the meat cooler. It’s this passion that led to the eventual creation and success of the Texas Barbecue class.

An email that started it all

In the spring of 2009, the university sent an email inviting professors to pitch small-section courses on any topic that would draw student interest.

“I don’t know why I read that email,” Savell said with a chuckle. “But I opened it, looked at the list of other classes and saw they were teaching one over baseball. I thought to myself: if you can teach a class about baseball, why can’t we teach one on barbecue?”

And so it began. Texas Barbecue came to life, led by the experience and excitement of Griffin, Riley and Savell. The Rosenthal facility was only available on Friday afternoons, so that’s when the class was held.

“We started with 15 students that first year,” Savell said. “Eventually, the university phased out those small-section classes, but our barbecue class stayed.”

Since then, the class has continued to grow in both number and fame. In 2024, a record 88 students were enrolled. The freshmen, however, only account for about half of the people in the room during each class period. Others filling the room include visiting family members or friends of students and teaching assistants, all former barbecue class students who fell in love with the culture and didn’t want to leave it behind after freshman year.

While most college courses have one to two teaching assistants, Texas Barbecue has nearly 75, all sporting maroon polos and likely helping with meal preparation or student engagement.

“I’m outside cooking most of the time,” Griffin said. “The teaching assistants are out there with me. I get to spend a lot of time with them, and we sure do have some fun.”

Where lecture and life lessons meet

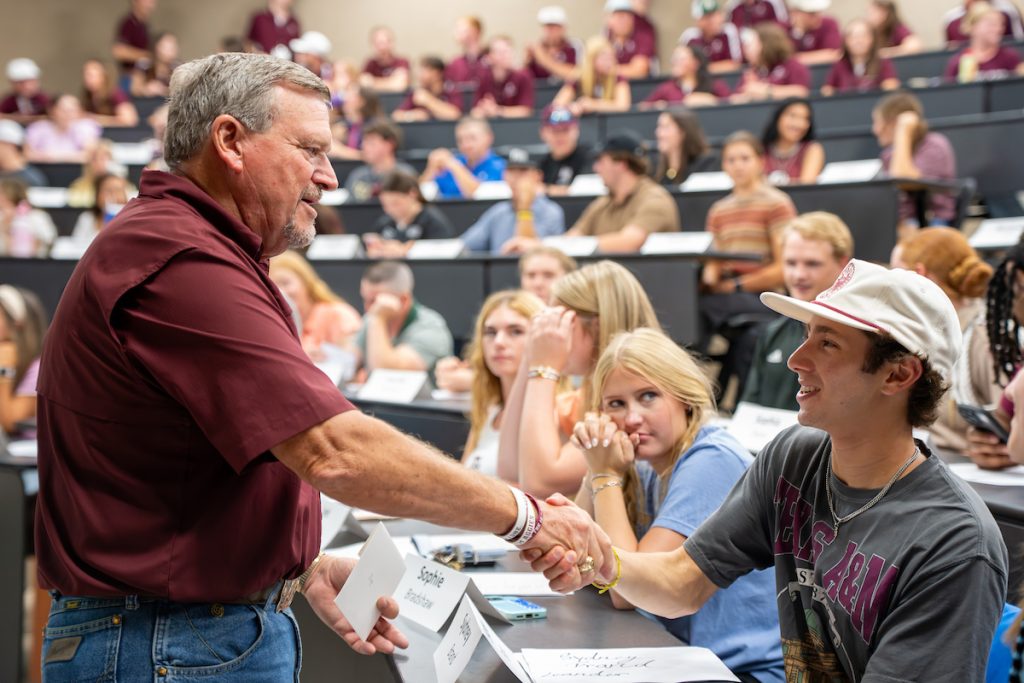

Each week brings a new topic or cooking style. Students arrive early to network and chat with friends before the 4:10 start time. Griffin, Riley and Savell float around the class sharing hugs, jokes and words of encouragement with students who might’ve had a hard week. Some teaching assistants help oversee the pits and prepare side dishes while others greet freshmen at the door.

Class begins with a lecture on the week’s theme. Then everyone heads to the pits to watch technique and safe handling. To end, the group returns inside to discuss recipes for side dishes, a crucial part of the class led by “Mrs. Jackie,” Savell’s beloved wife of 50 years.

But lecture isn’t just about barbecue; it’s about making students feel seen, heard and understood. Class discussions jump from dry rubs and wood pellets to how to change a tire and why a support system is necessary.

“When we were freshmen here, there was a group of faculty who cared about us, and they made sure we knew it,” Griffin said. “These students need to see that we really care about them, not just through our words, but by making them feel like we really understand.”

Fostering the family feel

After 50 minutes of formal instruction, most classes would disperse, but of course, this is no ordinary class. Texas Barbecue shifts into dinner. Students line up in the hallway while teaching assistants serve plates, a tradition that sums up the heart of the class.

“In high school, upperclassmen are seen as the big dogs,” Riley said, “But in this class, it’s the reverse. The older kids are here to serve the younger ones and make them feel at home. Nothing is below their dignity.”

Like many family dinners, the meal is where stories surface, stress drops and friendships settle in. The culture forms because people show up for each other week after week.

When asked how they want the freshmen to feel when they leave Rosenthal every Friday evening, the three professors paused to contemplate before answering.

“Loved,” Savell said.

“Like they just left after time spent at home,” Griffin responded.

“Comfort. Family,” Riley shared.

By the end of the semester, students know how to cook a brisket and make corn salad. More importantly, everyone in the room knows each other by name. When their friends ask why they chose a Friday afternoon class, they can smile and say that it’s not a class. It’s a community.

PHOTO: Texas barbecue has become an iconic culinary and cultural dish. The Brisketeers and pitmasters around the state continue to push the boundaries of the low and slow science behind barbecue. (Courtney Sacco, Michael Miller/Texas A&M AgriLife)