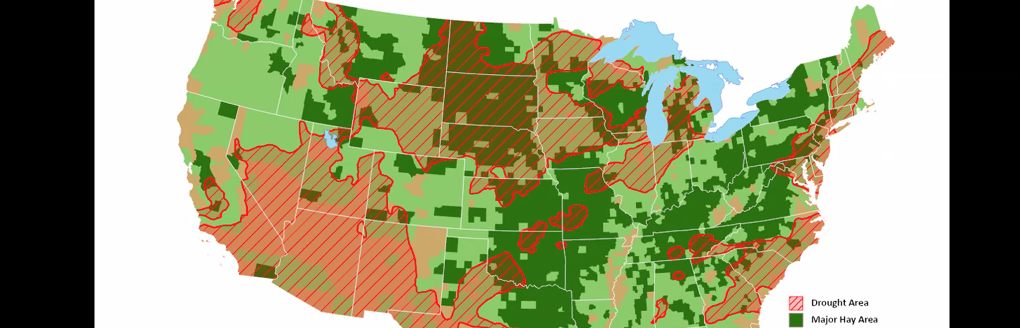

Agriculture, no matter what part of the United States it’s practiced in, has its fair share of challenges. Arkansas is no different.

Chandler Arel, soil and water conservation instructor with the University of Arkansas, said during the Ag Media Summit agricultural tour this past summer, the state faces numerous challenges each year. In his opinion, they include:

—Unsustainable groundwater use (4.7 million irrigated acres equals about 1.7 trillion gallons of water and uses about 86% groundwater.)

—Degradation of soil. Loss of soil fertility via erosion and runoff.

—Excessive nutrients and sediment in surface water.

—Balancing conservation with profitability. Trends show lack of adoption without federal and state programs.

“There are estimates that within the next several decades, our ability to adequately irrigate our crops in eastern Arkansas will be diminished,” he said. “Obviously, we have a very negative impact in the same area of the state where agriculture is so common.”

Soil degradation has taken its toll on many fields in the state.

“As you strip away natural fertility, you have to supplement that with chemical fertility,” he said. “Excessive nutrient and sediment loss from landscapes in eastern Arkansas has contributed significantly to the decrease in quality of water within the Mississippi River watershed.”

Arel said that goes hand-in-hand with the problem Arkansas has had for decades with unsustainable groundwater use.

Aside from the soil science aspect of agriculture, producers have been faced with “tremendous problems” in balancing conservation with profitability in their businesses—if they’re profitable at all to begin with.

“There are several past years where Arkansas farmers, on average, have lost money,” he said. “It’s difficult to tell a farmer, you need to be putting more and more effort into these conservation practices, and they’re already spending 78 hours a week just trying to make their business profitable.”

Those can be hard conversations with any farmer, especially when you look at the history of soil and water conservation programs in the U.S. and they have been positive for their livelihood.

In the research world of agriculture sciences, it’s becoming more popular to have the conversation about how farmers can become more resilient to climate change.

“We’re expecting intensification of things like drought, increased days of the year where we experience high overnight temperatures, increased pressure from diseases, pests,” he said. “We anticipate that the intensification of climate change would likely impact every single aspect of agriculture, business and from a science perspective, so we have to come up with ways now to deal with that in the future.”

One of the ways U of A is contributing to this kind of conversation is having people like Arel on staff and helping producers change their practices to allow them to adapt. When questioned about the Environmental Protection Agency’s decision to repeal the science that discusses climate change, he offered his thoughts.

“I would say that in any instance where a problem is not being dealt with explicitly, we’ve identified climate change as the problem in agriculture for decades now,” he said. “In any situation where we go back on that, us in the scientific community don’t feel as though that problem has gone away.”

Arel said in the Division of Agriculture, researchers don’t identify problems without solutions.

“So, as these problems have faced Arkansas for decades, some longer than others, we have conservation practices that we recommend Arkansas farmers to try to combat these challenges,” he said. “Generally, these conservation practices address the restoration and protection of our natural resources, being soil, water and atmospheric resources.”

One practice Arel does recommend is to use cover crops to protect the soil, as well as conservation tillage, to help decrease soil burdens and allowing residue to cover the soil throughout the growing season.

“In the off season, we also want to be efficient and responsible with the management of soil fertility, enhancing nutrient and irrigation management,” he said. “So that has actually been a very good deal in Arkansas, trying to make sure we’re only applying as much fertilizer as we need, and only keeping our fields as irrigated as we need.”

Besides helping with water efficiencies, researchers also encourage using alternative organic soil amendments.

“We have a very large poultry industry in the state of Arkansas and farmers have been using poultry litter as an organic amendment for decades. That continues today,” he said. “And then there are more novel, newer organic amendments, things like bio char, which is a charcoal-like product that has some promising research behind it in being able to hold on to soil fertility and keep those nutrients in the soil.”

Arel and his counterparts recommend a “suite of conservation practices” because they have visible, quantifiable results on solving issues.

In the world of soil science, Arel said the consensus from researchers is to encourage farmers to enhance their soil health.

Discovery farm solution

One way to find an effective solution for farmers has been the Arkansas Discovery Farms with an emphasis on sustainability through monitoring, demonstration and research practices.

An Arkansas Discovery Farm is essentially a private farm that’s agreed to collaborate with the University of Arkansas, and the farmers allow the university to work on their farms, implementing different technologies, monitoring different metrics that are happening on the farms, and trying to make sure that these conservation practices are working.

There are five main goals within the program and includes the need to assess practices.

“We have a pretty robust on-farm verification program where we have samplers to get these actual metrics to make sure that these practices are working,” he said, with a point of emphasis on making sure money spent on practices is a wise use of resources.

The scope of the program is quite broad, covering “pretty much the entire state of Arkansas,” Arel said addresses dairy, peaches, rice, corn, soybeans, and forestry sectors.

The program is supported by a host of sponsors and industry stakeholders to ensure research conducted addresses the needs of Arkansas farmers in a proactive manner. They’re designed to operate for five to seven years during which time water quality analysis and data reveal the effectiveness of conservation practices employed at each site.

According to the U of A, there are 13 active discovery farms and production systems selected for study that are both crop and livestock based and represent the diversity of Arkansas agriculture. The overarching goal of the Arkansas Discovery Farms program is to determine the effectiveness of water and soil conservation practices utilized on working farms.

At each site, conservation practices selected for evaluation are based upon the interests and wishes of the farm owner and may coincide with regional water or soil quality issues common to many producers in the area. Research is coordinated by faculty from the University of Arkansas Division of Agriculture and is conducted in collaboration with federal and state agencies promoting conservation of our natural resources.

It does take some encouragement to get farmers to sign up for the program and get the ball rolling. Arel said relationships between Mike Daniels, a soil and water conservation specialist with the university, and farmers have helped garner participation in the studies.

“I would say that Dr Daniels’ relationships with farmers across the state, and the kind of reputation and renown that he’s earned as a professor, is one of the strongest ways that incentivizes farmers to work with Arkansas discovery farms,” he said.

Arel said he can’t find a downside with participation—farmers get free information, monitoring techniques on the farm and help to improve efficiency and knowledge.

The process has been a “tremendous way” to encourage farmers to be a part of the program, according to Arel.

For more information visit https://aaes.uada.edu/centers-and-programs/discovery-farm-program/.

Kylene Scott can be reached at 620-227-1804 or [email protected].