Cattle inventory remains at historic low

Livestock economists said the Jan. 30 cattle inventory report showed what they expected—the nation’s beef herd is not expanding.

The United States all cattle and calves count was 86.2 million head as of Jan. 1, 2026—a 300,000 head drop from the previous year, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The all-important beef cow count was at 27.6 million animals, which was also down 284,800 head from a year ago.

For livestock economists it is a sign the nation’s cattle herd is continuing to shrink.

“The long-term forces of beef per cow are decades long and not new,” said Glynn Tonsor, a professor in agricultural economics at Kansas State University. “Furthermore, political and broader business environment risk growing—notably in late October and early November—likely tempered some expansion interest and perhaps slowed the magnitude of interest among those seeking to rebuild.”

Oklahoma State University Extension livestock economist Derrell Peel had hoped the count may have at least shown a small plus or remained the same.

“I thought it was possible that it would be up fractionally and so for it to come in lower that’s probably the biggest surprise,” he said.

Tonsor said on balance it was aligned with his expectations, adding the main conclusion is the national breeding herd (both current cow inventories and heifer retention for future) was effectively similar to prior year levels.

High Plains numbers

Oklahoma did not have a change in its beef cow count at 1.96 million head, but was one of the few states that did not see a decline. Kansas was down 7%, Wyoming was down 5%, Montana and New Mexico were both down 4%, Missouri was down 3%, and Iowa, Nebraska and Texas were down 1%. South Dakota was unchanged at 1.45 million head as was Arkansas at 848,000 head. Minnesota (up 4%) and Colorado (up 2%) were the only two states that showed an increase as they totaled 355,000 and 620,000 head, respectively.

Texas remains the top state with 4.045 million head, followed by Missouri at 1.806 million head, Nebraska at 1.56 million head, South Dakota, Montana at 1.232 million head, and Kansas at 1.146 million head.

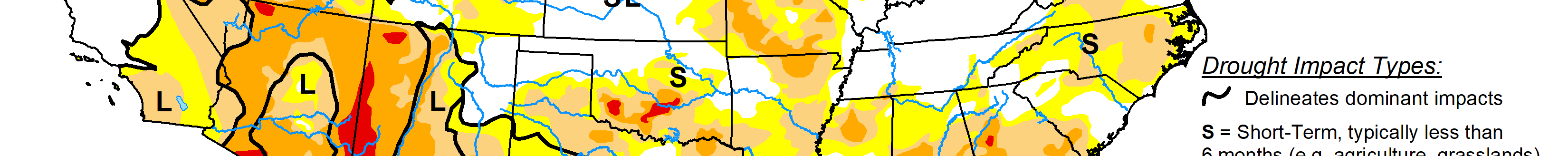

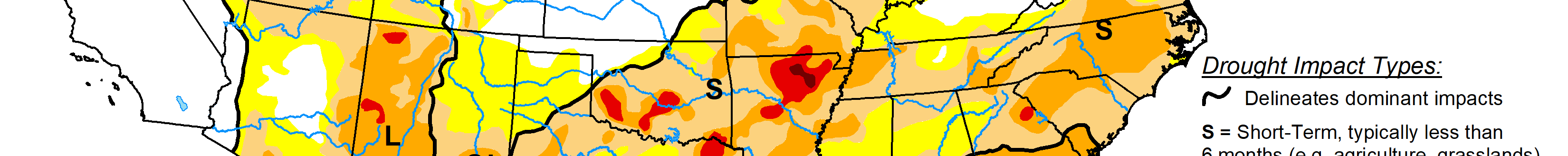

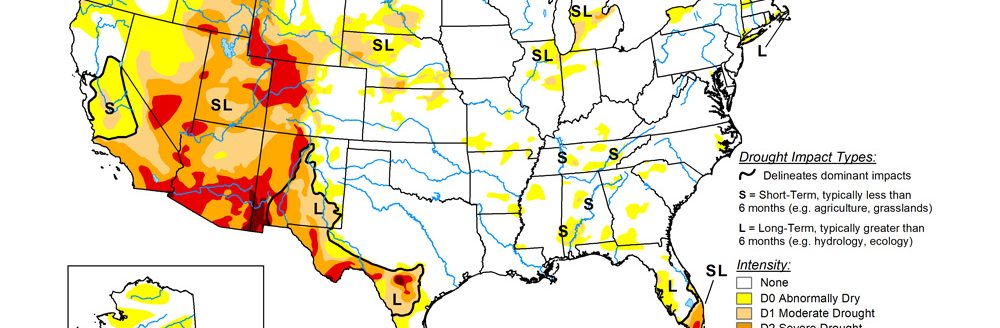

David Anderson, a professor and Extension specialist at Texas A&M, said the numbers reflect a combination of reasons. The U.S. Drought Monitor shows a persistent drought in much of the prime cow-calf states.

High prices encourage ranchers to sell, he said. “Even though it also signals producers to expand, it’s a balance—the check today in hand versus the future earnings of that heifer. People remember the last cycle when prices dropped fast because we expanded fast.”

Higher interest rates and other costs are important, he added. Some bankers are reluctant to loan money based on replacement costs. Still, it can be an opportunity to capture some high calf prices.

“I think the one thing it really confirmed what we all thought and that was that there isn’t any fast growth going on,” he said. “Fewer cows, small increase in heifers—really not a big surge in growth in response to record high prices.”

Tonsor said Texas having a comparatively large heifer retention growth may be worth monitoring, which could possibly reflect inner-state efforts to adjust given lower available import supplies of Mexican feeder cattle.

Have we hit a low?

Tonsor said the Jan. 30 report most likely means the low in inventories are indicative for this cycle.

“It is important to note that one, we get more beef per cow than ever before; two, beef production rather than hoof-count measures are most important supply metric; and three, long-term trend is fewer cows (suggesting future cycle lows could be lower),” Tonsor said.

“I think it’s pretty close to the bottom,” Anderson said. “For growth we’ll need to slow cow slaughter even further and then add heifers. While the number of heifers held for replacement was bigger it was only about 41,000 head more than a year ago. That’s a small number and with a smaller calf crop also then it’s even harder to have the numbers to expand.”

“I thought 2025 might be the low (at 27.892 million),” Peel said. “Now we have a number that could be the low, but honestly we won’t know for sure until this time next year. I certainly expect that it’s close to the low.”

Anderson expected cow numbers would be close to a year ago’s level, but he thought it was possible for slight growth because of the decline in cow slaughter and not because of heifer retention.

“I think it is a little surprising that it was down just over 1 percent but, I don’t think the direction is a big surprise but, just the magnitude,” Anderson said. “I did expect a little bit of growth and had certainly told some producer audiences that.”

Ten years ago, the market responded with a much quicker rebuild, but now the industry has a historically slow herd expansion, Peel said. Since 2023, industry watchers thought signals were in place for expansion. They have failed to materialize.

“There was a small uptick in the beef replacement heifers, which Is a positive sign that maybe marginally we’re turning the corner a little bit,” Peel said in looking at those numbers adding that overall there was still not enough numbers to promote a change in direction.

The reality is there’s little prospect for growth in 2027 and likely that means an expansion is further out, he said.

Cow-calf producers continue to receive prices where they have incentives to sell rather than retain their herd, Peel said. Producers have sent a message they want to improve their financial situation and are taking advantage of what the market is giving them.

“At some point in every cattle cycle producer expectations flip, and they switch from the ‘bird in the hand’ to a longer term mentality of investing in the future,” Peel said, adding that politics weighed it he market last fall and that created volatility and uncertainty.

There are individual producers who have expanded their operations in recent years, he said, but in total it has not changed the direction to an overall upward movement.

“We probably aren’t going to see a really aggressive push, but I think it will slowly gain momentum through this year if we have a good growing season and we can some of the external influences to a minimum,” he said.

Other aspects in the chain

As of now, the livestock pipeline is stretched thin, Peel said, and it is going to stay that way. “We still haven’t had any significant heifer retention, which means a tight feeder supply and it’s going to get tighter at some point until we move toward a longer-term investment in the future.”

Producers with stocker operations and feedlot operators are facing tighter margins even with less expensive feed and packers have struggled the past couple of years, Peel said. Retailers have not struggled as much as packers, but they too will see the impact of having less beef available and there will be a limit to how much they can pass on higher costs.

“Feedlots have had actually had the best run so far through this, but I think their situation is also going to change noticeably as we go forward,” Peel said. “They have been able to hold inventories pretty high and that keeps their operating efficiency in a pretty good spot.”

However, while he sees higher prices, he doesn’t see them going up as quickly as they had in the past year and that will create a squeeze.

Silver lining

The economists said the cow-calf producers have benefited the most in the past couple of years. Peel said cow-calf producers are price takers and he said they should enjoy the prices they receive and continue to take advantage of that opportunity.

“Everybody else above the cow-calf sector in this industry is a margin operator,” Peel said. “All of those margins are generally in some degree being squeezed at this point because everything is going from the bottom up.”

Getting out of drought conditions would help, Anderson said. Prices and profits are certainly there to start growth plus consumer demand has continued to be strong, but also expenses and interest costs are factors.

“It’s worth remembering too that by increasing beef produced per head to record levels—dressed steer weights over 980 pounds—we are offsetting some fo the cattle we need buy boosting beef production pounds per head,” Anderson said. “That would reduce the number of cattle we need.”

The Texas A&M economist also noted in the Jan. 30 report, the number of stockers on small grain pastures was up almost 200,000 head.

“That was a little surprising given drought conditions and some problems getting stands established in wheat pasture country and the lack of stocker cattle to be had even at these high prices,” Anderson said.

Advice to producers

Tonsor said confirmation of a tight calf crop is not surprising, but important to note. Making adjustments to right-size operations, having a firm handle on both total and per-head production costs (knowing your break-even) is always important.

Peel said if producers are wanting to maximize profits, particularly at the cow-calf level, they will still need to manage all their costs and put themselves in a position to reap the benefit.

“The market wants calves, so produce calves and sell them,” he said. “For everybody else it’s even trickier so the cost management side is important, and it will be harder. You will have to look for opportunities and frankly in some cases you’ll just have to figure out how you’re going to weather this storm.”

On the cow-calf side, Anderson said ranchers should have a high level of confidence that prices will be strong and they can continue to make money. The backgrounder, stocker and feeders are going to feel more pressure due to tighter margins.

“It also keeps the pressure on the packers as well,” Anderson said. “The lack of cattle and high costs will keep them losing money. That will cause even more pressure on existing plants to stay in business and pressure on new plants trying to startup to even get off the ground. Our packing capacity will be under a lot more pressure this year and for a longer period of time because we aren’t growing the herd.”

Dave Bergmeier can be reached at 620-227-1822 or [email protected].