Circling solutions for black vulture attacks

Vultures, often thought of as the birds of death and decay, have a reputation for scavenging roadkill and signaling mortality from the sky. However, the black vulture is also known for attacking and killing newborn livestock. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Wildlife Services, black vulture attacks on cattle increased by almost 25% between 2020 and 2022.

The National Cattlemen’s Beef Association indicates black vultures kill 2.1 million calves per year, leading to $4 billion in damages. Unlike other species of vulture, black vultures are increasing spatially and numerically, putting more livestock at risk and hurting cattlemen’s bottom line. According to NCBA, since 1990 black vultures have seen a 468% increase in population with more than 190 million birds in the U.S.

Black vulture ecology

There are only three species of vulture in the U.S., including black vultures, turkey vultures and California condors. Even though they are protected through the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, black vultures are unique from other species, because they are temperate migrants and do not have the typical large north-to-south migration.

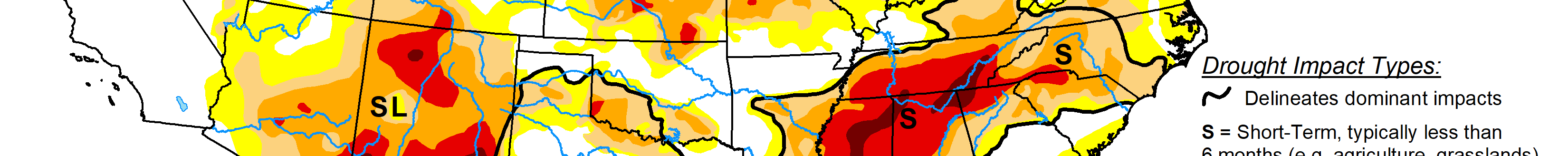

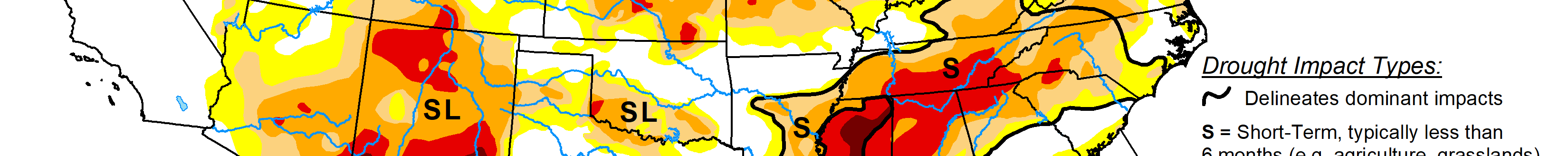

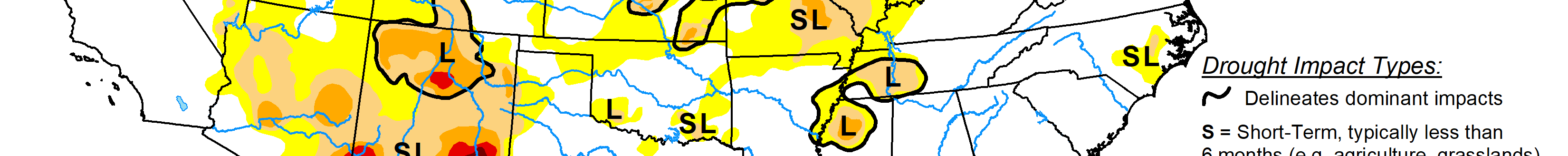

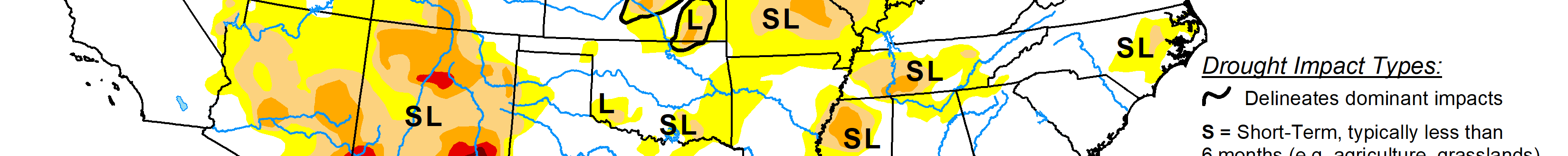

Bryan Kluever, supervisory research biologist at the USDA’s National Wildlife Research Center, said black vultures are found in every contiguous state in the U.S. They are primarily an eastern species, but they are expanding northwest into states such as Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, Oklahoma and Arkansas.

“Black vultures are more scavengers than they are hunters,” Kluever said. “There is evidence that they will occasionally take sick and small livestock, and sometimes while an adult animal is in the act of trying to protect its young, those animals can potentially be injured as well.”

Black vultures are the smallest of the vulture species, and their wingspan is much shorter than a turkey vulture or California condor, but they are also one of the most aggressive species.

“Black vultures have less sense of smell than turkey vultures, so they are much more visually based hunters,” Kluever said. “Oftentimes, they will fly above turkey vultures and wait for them to locate prey through their sense of smell. Then the black vultures will come and take over the dominance of that carcass and the turkey vultures will have to wait in line.”

Although they are creating major challenges for livestock producers, vultures are vital to the planet because they rid the environment of carrion, or dead flesh. Kluever said a world without vultures would be disastrous.

“Other parts of the world have found that mammalian scavengers just can’t keep up with the pace,” Kluever said. “But when we do have a species that increase, we sometimes have escalations in human wildlife conflict. We are trying to better understand why these conflicts are occurring, and hopefully trying to come up with new tools to mitigate that conflict in a way that allows humans and wildlife to coexist.”

Non-lethal measures

Cattle producers that are plagued by black vultures can utilize several non-lethal strategies to deter them from killing livestock. However, Kluever said every situation is unique and not every tactic will work for every producer. One of the most common tools to discourage black vulture presence is to hang a vulture in effigy by its feet.

“Hanging a dead vulture near an area where living vultures like to congregate tends to scare them away from the area,” Kluever said. “However, if you’re dealing with a 2,000-acre cattle ranch, hanging effigies throughout is not practical.”

Additionally, Kluever said black vultures like to roost in large, dead or dying trees and removing that habitat can prompt them to leave the area on their own to find better roosting opportunities. Loud noises and lasers can also make black vultures retreat and leave an environment.

Kluever said livestock protection animals have also been reported to be useful in fending off black vulture attacks. To lessen the likelihood of attacks, cattle producers can keep expectant animals penned up close to human activity until they have calved, and the offspring is no longer an easy vulture target.

“There’s just no silver bullet with human or livestock black vulture conflicts, so it really is site specific,” Kluever said.

If a black vulture kills a calf or lamb, the USDA Farm Service Agency offers the Livestock Indemnity Program to reimburse livestock owners for their animals. A necropsy must prove that a black vulture killed the animal for the owner to be reimbursed for the necropsy and the value of the livestock.

“If a black vulture does kill an animal, they tend to eat the evidence really quickly,” Kluever said. “To examine hemorrhaging and other things, you really need to get a calf necropsied within 24 hours to 48 hours.”

License to kill

Although black vultures are a protected species, the problems they pose to cattle producers, along with their plentiful populations, have allowed for a caveat to their migratory bird status. In states such as Missouri, Oklahoma, Nebraska, Texas, Kansas, Arkansas, Indiana, Iowa, Colorado and Illinois, permits are available for ranchers to kill black vultures threatening their livestock. Depending on the state, sub-permits can be granted through state Farm Bureau organizations or directly through the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Davin Althoff, director of marketing and commodities at Missouri Farm Bureau, said MFB has collaborated with the Missouri Department of Agriculture, Missouri Cattlemen’s Association, University of Missouri Extension, USDA and the Missouri Department of Conservation, to provide resources for livestock producers on the black vulture problem.

“We applied for the permit four years ago because we continue to hear from our producers that they’re experiencing problems with black vultures,” Althoff said.

Most state permits are free, but only livestock owners are allowed to obtain them. Originally, Missouri’s sub-permit allowed the holder to kill five black vultures in a year, but in 2024 that number was increased to 10. Oklahoma also increased its permit limit to 10 in 2024. Althoff said in 2022, MFB issued 38 sub-permits; in 2023, 164 producers obtained sub-permits and to-date in 2024, 257 sub-permits have been issued.

“Livestock have a tremendous value, and when you lose a calf or a baby lamb, that’s a significant loss for livestock producers,” Althoff said. “This permit is a resource for them, a tool for the livestock producer to be able to take action to try to mitigate the challenges that they’re experiencing.”

Althoff said some livestock owners only obtain a permit so they can kill one black vulture legally, and they use the carcass as an effigy to ward off other black vultures.

“We’ll have some producers that may take one or two and hang their takes in effigy, and that takes care of their problem,” Althoff said. “For some larger producer who have a lot more ground to cover and may be calving at multiple farms, 10 kills may not be enough.”

The black vulture issue has even attracted attention from Congress. Two bills, HR1437 and S3358, both named the Black Vulture Relief Act of 2023, are designed to allow livestock producers to kill black vultures without a permit. The Black Vulture Relief Act has been introduced to Congress and is currently awaiting consideration.

“Black vultures are most likely going to continue to expand spatially and numerically, so you’re essentially going to have an increase in the conflict, just by proxy of probability,” Kluever said.

To learn more about black vulture permits, contact your state Farm Bureau office or U.S. Fish and Wildlife.

Lacey Vilhauer can be reached at 620-227-1871 or [email protected].