There are more working parts to a drought than just lack of precipitation.

That’s according to Dave DuBois, state climatologist for New Mexico, who was the featured speaker of a May 21 webinar organized by the state climatologists from New Mexico, Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas in cooperation with officials from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the Southern Climate Impact Planning Program, the National Drought Mitigation Center and the High Plains Regional Climate Center.

“Drought is not only precipitation and temperature, but it’s also longer term impacts of where does our water come from,” DuBois said.

Drought conditions in the southern Great Plains have been going on since last fall, DuBois said, and over the last three weeks, there hasn’t been much precipitation, especially in New Mexico. There’s only been a tenth of an inch recorded over most of his state. The farther east you go into Texas and Oklahoma, it gets spotty too.

“There’s a few areas that had some precipitation from all over the last three weeks, but over the majority of the area here it’s been pretty light,” DuBois said.

Data from the water year starts in October, and in DuBois’ analysis, since October 2017, a pattern takes shape.

“We start to see the longer-term impacts of drought, just looking at precipitation,” he said.

In the western Oklahoma panhandle, there are areas that have received less than 10 percent of their normal precipitation while some parts of west central Oklahoma are down 20 to 30 percent. Areas of southeast New Mexico have yet to see any precipitation since the beginning of the water year.

Temperature is another factor in drought impact, and many areas have seen above average temperatures the past couple weeks. Heat is an important factor in evapotranspiration, the process by which water is transferred from land to atmosphere by evaporation from soil and other surfaces and by transpiration from plants, also. Climatologists use the Evaporative Demand Drought Index to measure evaporation.

“The evaporative demand drought index shows a lot more stress on our plant systems out here and you’re seeing high impacts over the last 60 days over in large parts of the southern Great Plains,” DuBois said.

There’s less of an evapotranspiration effect the further east you go in Kansas, Oklahoma or Texas. But in the southwest, cropping systems and rangelands are suffering because the high rates of evapotranspiration.

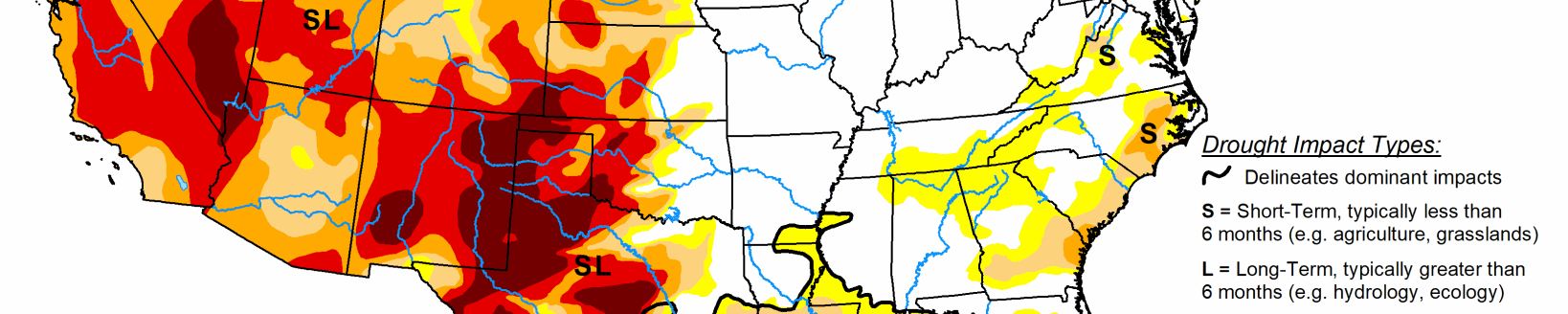

The May 15 Drought Monitor shows many areas that are in at least a D1 designation and many more are in varying stages of drought.

“As you go further into the drought intensity, we’ve introduced exceptional drought in parts and almost all of the states here—Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma and Kansas; and we’ve increased that over the last week,” DuBois said. “Especially over in New Mexico where we’ve been seeing a lot of impacts of drought.”

Some areas have seen some small improvements, but overall there’s been degradation over a lot of the areas in the southern Great Plains.

“There has been some relief in a couple areas,” DuBois said. Sporadic rains fell in the Texas and Oklahoma panhandles as well as Kansas and Colorado during the last full week of May.

Tough go for wheat

Wheat is suffering. Kansas and Texas are facing some of the worst condition indexes in recent years forcing farmers to abandon acres in an attempt to recoup some of their expenses.

“The abandonment rate in Texas compared to last year rose from 50 to 66 percent of the winter wheat planted and from 2.5 to 3.1 million acres of abandonment for winter wheat,” DuBois said.

Sign up for HPJ Insights

Our weekly newsletter delivers the latest news straight to your inbox including breaking news, our exclusive columns and much more.

Oklahoma has similar condition index numbers. In recorded history, only three years have been worse than 2018.

“If we look at the Oklahoma winter wheat abandonment in percent, and this is going from 1995 to 2018—compared to last year the winter wheat abandonment rose from 36 to 53 percent planted average,” he said.

That corresponds to 1.6 to 2.3 million acres.

“It’s an all time record for Oklahoma,” DuBois said. “So that’s very significant.”

DuBois has heard from people who are in the middle of the drought impact. Some cities are facing municipal water restrictions already, with plans to continue those restrictions through Sept. 15. Many winter wheat acres are being cut and baled for feed instead of being harvested or zeroed out by insurance.

“I’ve been seeing some reports in New Mexico and western Oklahoma of ranchers selling cattle, culling cattle,” he said. “Some are starting to haul water to their cattle.”

Prior to the late May rain events, many of the wildfire areas in Dewey County, Oklahoma, had little regrowth of burned vegetation in the Rhea fire area.

“Highs have risen into the upper 90s at times with high winds 40 to 50 miles per hour moving nothing but drifting sand across the burn scars,” DuBois said.

At the time of the webinar, the five- and 10-day extended forecasts didn’t look promising for the southern Great Plains, according to DuBois. There were a couple areas in west Texas and eastern New Mexico that seemed like they might get some rain and they did. He said the next 30 days are critical as far as rainmaking precipitation events go.

The NOAA Climate Prediction Center’s temperature outlook from June to August probability maps are showing it will most likely be above average temperatures.

“That’s to be expected. We’ve been seeing these for months,” DuBois said.

The precipitation predictions for June to August for most of the southern plains show equal chances for above average, normal or below average precip.

“Equal chances is actually good,” he said. “We’ve been seeing a lot of below average so that’s sort of a good sign.”

DuBois believes if it shows equal chances for precipitation, then it’ll probably be near normal precipitation, which would be helpful, he added.

The seasonal drought outlook shows drought remaining, but improving in parts of the southern Great Plains.

“That’s likely driven by the fact that we’re likely seeing from the climate prediction center some near normal equal chances which is a good sign,” he said. “There’s some good news, but not real good news. Better than seeing something getting worse.”

Kylene Scott can be reached at 620-227-1804 or [email protected].