Soil health commitment delivers long-term success

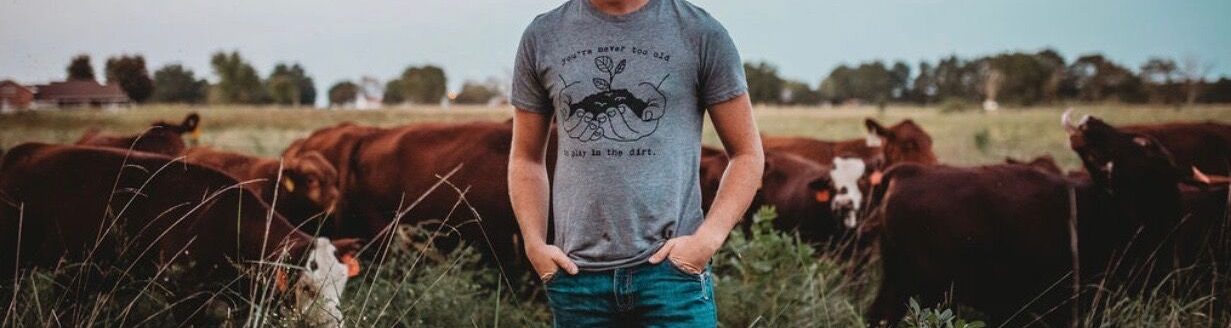

When it comes to soil health, Nick Vos has a simple message—put together a plan, start within your means and measure results.

Vos, 46, farms about 600 acres of wheat, corn and sorghum in Stevens County, Kansas, and Texas County, Oklahoma. Vos and his wife, Johanna, have two daughters, age 14 and 10. In 2006, Vos had the opportunity to move to the Hugoton area in southwest Kansas to join a farming enterprise, which he stayed with until 2014 when he parted ways with them and became a first-generation American farmer.

The South African native grew up on a vegetable farm in the Limpopo province, where spoon-feeding vegetables with prescription fertilizer recommendations was the norm.

“The biggest difference I noticed when I got here was most farmers applied fertilizer up front,” he said. “That did not make sense to me.”

He soon understood why farmers, because of their tight schedules and limited work force, would apply bulk supplies but he often wondered if there were other ways to distribute and protect nutrients against volatilization and leaching. It is that mindset that got him thinking more about conservation, not only in nurturing the ground and keeping it from blowing but also to preserve water. He lives in a region of the state that faces a decline in the Ogallala Aquifer.

In his first venture from 2006-10 they used traditional farming and tillage practices for the region. The operation used a strip till cropping system and from a conservation standpoint that gave him a leg up in wanting to do more. “The strip till worked really well, but in heavy rains, we still had some washouts and run off.”

“I asked myself is there a way that we could be better. I did not have a grandpa or dad to tell how to do it or what not to do, either way. I have always been stubborn and simply wanted to learn more.”

New ways

Vos credits Ray Archuleta, a conservation agronomist, and a no-till conference he attended in 2010 for getting him thinking about using crops that could help save moisture and build the soil back up. “We have lost a lot of organic matter since they broke out the Plains, and I was reading on ways to restore that.” During that time, they also purchased a John Deere no-till air seeder and no-tilled all their wheat acres in the fall. That helped prevent the soil from blowing during the winter.

The cover crops process was one that intrigued him though.

“That’s when I saw the upside,” he said, noting that implementing cover crops in a traditionally dry region, which in the 1930s was associated with the Dust Bowl, was a challenge. The mentality is, there is not enough moisture to raise cover crops and a cash crop. For the most part that view still has not changed.

Vos says he can change that narrative based on his own experience. He plants cover crops after almost every cash crop. Benefits include improved water infiltration, better nutrient cycling, better nutrient holding capacity, and, in turn, higher margins. “Once you see and experience the results, the moisture used to grow the cover is offset by far by all the benefits you get in the long run.”

With normal moisture he receives from October to April, his soil is able to recharge to a higher level than before they started using cover crops. He started with some basic covers like millets, radish and sunn hemp that followed wheat harvest. After experiences with all sorts of species, Vos uses Archuleta’s method of kicking out the worst performing specie and always adds something new.

When he compares the nutrient levels with tissue sampling, it has consistently indicated improved levels. Nutrients were not previously accessible due to being tied up by the soil, and the lack of biology. “We see a more balanced nutrient analysis every year.”

He has seen that the totality of the practices making the soil healthier and it means cost savings in fertilizer and chemical expenses. This in turn helps for an improved bottom line. “We have not applied phosphate to our corn crop the past three years and we are still seeing adequate levels in our tissue samples.”

“We are seeing higher margins each year,” he said, adding that it helps a lot when you are a beginner farmer and trying to establish.

The journey

Soil health is a long-term journey, Vos says. His advice to producers, regardless of size, is to start small and evaluate results when trying cover crops. Even if a farmer has thousands of acres, he suggests starting with 160 acres, for example, and trying to keep living roots on it all the time between cash crops. Then evaluate the results.

“Cover crops are not a magic wand,” he said. “It takes three to five years to see the benefits. The guys need to take a small percentage and stick to it. I do think the long-term results are absolutely phenomenal.”

Today’s producers have to work with bankers and landlords who are traditionally driven by yield-based results when they pencil out loans and leases. This makes it hard for anyone to start doing something that’s not the norm.

Keeping track of results and sharing those with your banker or landlord is important. “If a farmer wants to improve his bottom line and is serious about improving his margins I don’t see why his banker or landlord would oppose the idea of increasing their soil’s ability to produce better crops with less inputs. “

When Vos speaks he also takes a pragmatic approach to his presentations. He believes it is important to share stories of success and be upfront about drawbacks and challenges. He will apply that at the second annual Soil Health U on Jan. 23 to 24, in Salina, Kansas.

“A year ago when the first soil health conference was announced I think there was naturally a lot of skepticism, and even as a presenter, I was not sure what to expect. I was pleasantly surprised with the outcome. I think guys need to get out and learn what is out there,” Vos said. Then they can decide for themselves if it is something they can learn from or not.

His honesty and realistic approach struck a chord with his audience a year ago.

“I remember when I was on a panel and I know I raised a few eyebrows when I told guys if you have to till to get rid of herbicide-resistant weeds you have to do it,” he said. Everyone has to do on his or her operation what works and sometimes that means parking the sprayer and hooking on to a plow.

“It does not mean you give up,” Vos said. “It means you still have a lot to learn on how to do it better.”

While some aspects of soil health programs may seem controversial, he says that all he suggests is that people take time to listen and digest the information.

“I look at soil health like a new year’s resolution. If you try to do everything at once it won’t work. If you pick one thing and you focus on accomplishing it, that is how you gain momentum and get over the finish line without breaking the bank.”

Dave Bergmeier can be reached at 620-227-1822 or [email protected].