Nebraska Food for Health Center maps sorghum genes controlling human gut microbiome

We all have trillions of living microbes in our gut. Our diet shapes the kinds and abundance of microbes living in our gut, which are connected to health and well-being. But as scientists learn more about which microbes are associated positive and negative impacts on human health, a key question has remained unanswered: "How do we change our own microbiomes?"

The answer may be in the food we eat. Different foods, made from different crops contain a variety of fibers, polyphenols and other natural compounds can influence the abundance of different microbes within the human gut. Increasing our fiber intake by consuming whole grains vs food made from refined flour is one example. But what if different grains have different effects on our guts?

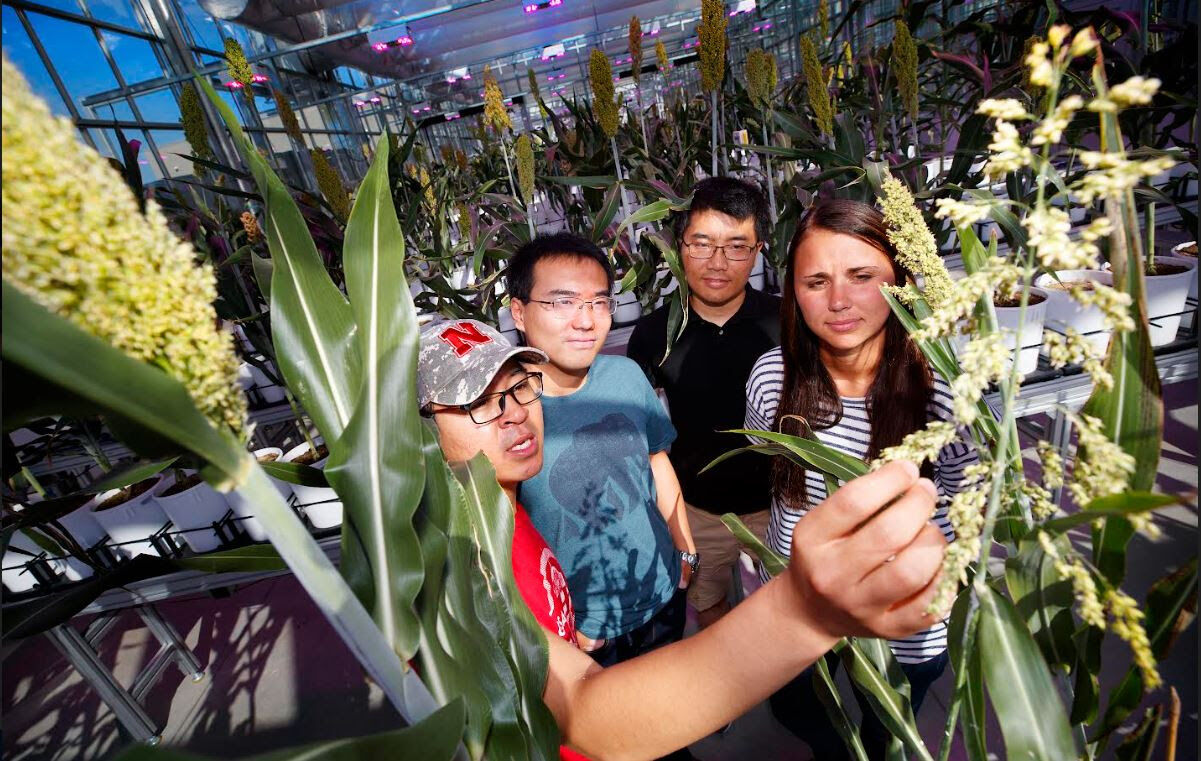

In a study from the laboratory of Dr. Andrew Benson that was led by Dr. Qinnan Yang, scientists at the Nebraska Food for Health Center demonstrate that natural genetic variation within crop plants can indeed play a major role in controlling growth of specific organisms in human gut microbiomes. In this study the researchers used sorghum, an ancient grain first domesticated in Africa that is grown and consumed around the world today.

Sorghum is known to have a large number of bioactive models that can stimulate cells in the human body, including microbes in our gut. Dr. James Schnable, a member of the Nebraska Food for Health Center who studies corn and sorghum genetics, provided grain from almost 300 different kinds of sorghum. Yang made flour from each of these sorghum lines and used a new automated system to measure the impact of flour from each kind of sorghum on the human gut microbiome, the team applied the tools of quantitative genetic to identify parts of the sorghum genome that affect how the gut microbiomes of different human beings responded to being fed sorghum.

In two cases, Yang noticed that the same region of the sorghum genome that caused major changes in the human gut microbiome was also controlling differences in the color of the sorghum seeds and sorghum flour. The team was excited when they realized that these two parts of the genome contained two genes, called Tan1 and Tan2, that control the production of condensed tannins, a group of compounds that add flavor to red wine and dark chocolate.

Sorghum varieties with intact versions of both the Tan1 and Tan2 genes had dark colored seeds and stimulated the growth of a set of microbes including Faecalibacterium, Roseburia and Christensennella while other sorghum varieties with mutations in either gene produced light colored seeds that failed to stimulate growth of these organisms. Beyond the excitement of identifying the actual genetic cause that can stimulate these organisms, the team was also energized by the fact that many studies show that these same organisms are quite beneficial for human health and are believed to help prevent conditions such as Inflammatory Bowel Disease.

“It’s so cool to see effect of Mendelian genetics in a crop plant working like a charm on human gut microbiome,” said Yang. “It really isn’t just about tannin or even sorghum. Now that we’ve shown plant genes can control changes in the human gut microbiome, we can use our approach screen hundreds or thousands of samples of different crops. That makes it possible for plant breeding programs to harness natural genetic variation in crops to breed new crop varieties that improve human health by promoting beneficial bacteria in the human gut.” Benson added, “this is remarkable to see plant geneticists, microbiologists, and food scientists working together to develop and improve a new generation of traits in food crops aimed at reducing diseases.”