Farmers have felt the crunch of higher expenses and lower farm-gate prices in the past year, and a study affirms those views.

Scott Brown, an Extension associate professor at the University of Missouri and interim director of the University of Missouri’s Rural and Farm Finance Policy Analysis Center, said the recently released spring 2024 farm income outlook did not yield any surprises. The survey included Missouri, Kansas, Arkansas and Nebraska. Each state is expected to see a decline in net farm income.

Trying to project farm income has become tougher because of black swan events, Brown said. A fire at the Tyson beef plant in Holcomb, Kansas, a trade war with China, the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of the Ukraine added volatility and sharp declines and upswings in prices and on expenses the past five years. A black swan event is defined by Investopedia.com as an unpredictable event that is beyond what is normally expected from a situation and that has potentially severe consequences.

“We see more record highs and lows,” he said, and volatility makes predictions tougher. Before events in the past five years, mostly it was Mother Nature that provided the largest unknown. She continues to be major force in the volatility puzzle.”

Interest expenses and fuel costs have hurt producers in the past year. With the latest inflation news, Brown said the Federal Reserve is not in a hurry to cut interest rates, and it might only be a half point, which was not the news many observers had hoped. Fertilizer costs have declined, but they won’t be at pre-COIVID prices. This year, many producers were able to get anhydrous ammonia and lock in a good price, and supplies are adequate, which will help producers as they go through the spring and summer.

Uptick slow for prices

Commodity prices may be on a slow rise. Much of the forecast on the grain side depends on the weather, he said. If corn hits 181 or 182 bushels per acre, then lower prices are expected, but in April there’s always uncertainty about how the growing season will unfold, he said.

“We tend to find states that have a heavier crops side of the equation are not doing as well, or we see a larger income swing than those states that depend more heavily on cattle like Nebraska, Kansas and to a certain extent Missouri,” Brown said in looking at it from a national perspective. “Those are the states that are faring a little better because they have more diversification.”

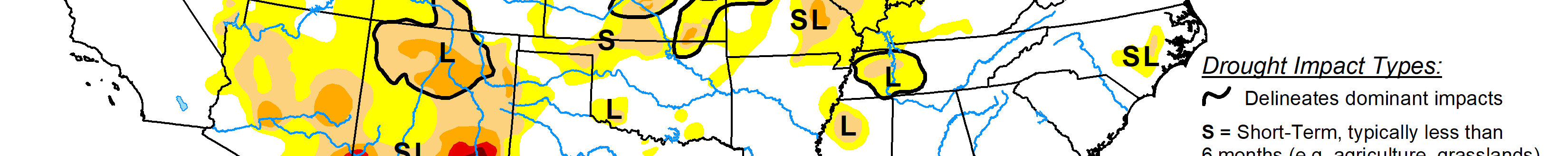

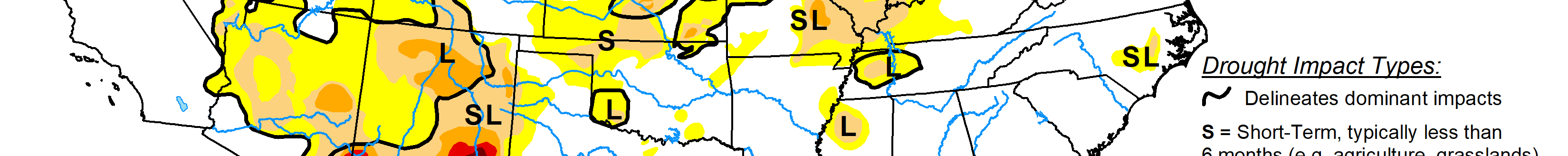

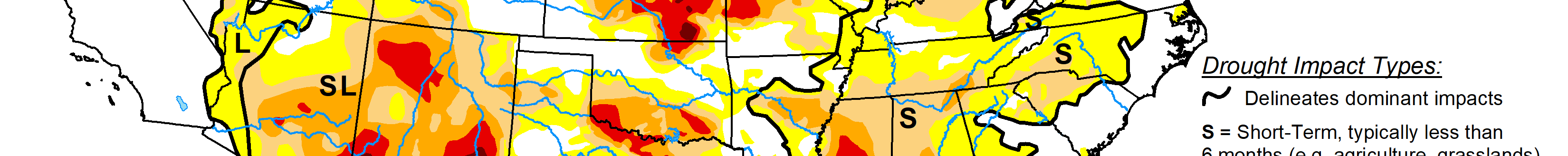

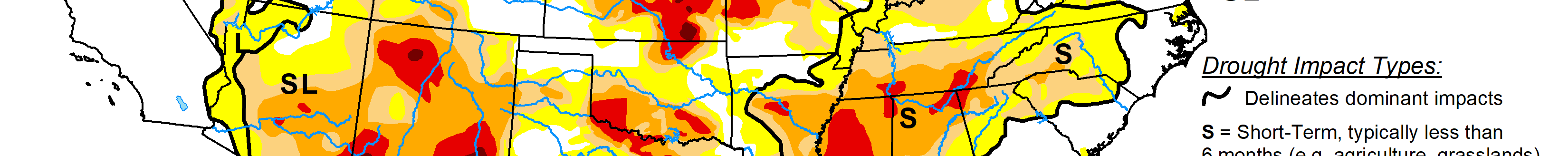

Brown believes the nation’s beef cattle herd will be slower to rebuild than 10 years ago because of drought and higher interest costs.

“If it gets dry again, and there are no forage supplies, we won’t be rebuilding anytime soon,” he said.

He also noted concern that older producers with smaller herds are exiting or considering leaving the cow-calf sector.

“They are leaving when things are good, he said. “It reminds me of the late 1980s and early 1990s when smaller dairies started to get out. With the older (beef) producers I can see some of that occurring again with cow-calf operations.”

The result could lead to greater concentration in the beef complex, he said.

Risk exposure

As Congress looks to write a farm bill, he hopes the representatives and senators understand that costs continue to be high, and revenues have come down from recent highs. “The cost squeeze is what we see,” Brown said.

He advocated a bill that can help manage risk better. While crop insurance gets the lion’s share of publicity, he hopes greater emphasis will be placed on the Livestock Risk Protection programs to help livestock producers.

Also, risk management tools need to be flexible to create an effective safety net without interfering with the marketplace, Brown said.

“A perfect policy today might need modifications tomorrow,” he said. “We all recognize Congress has a hard and tough job, and risk management is important, but it is more than revenue. It is also about costs.”

Farmers and ranchers may want to focus more on their risk management inputs and other aspects that affect the bottom line, he said.

While there are some dark clouds, he also sees farmers and ranchers generally are in better shape in comparison to historic downturns and benchmarks.

Expect tighter margins

As farmers plan ahead for 2024 and beyond, Brown said they will need to understand they are going to have tighter margins than they have experienced in recent years. They will need to reduce costs as much as possible without hurting their bottom line. Volatility is going to be a constant, which can mean record highs as seen earlier, but now the upcoming period will keep market prices in check.

“We’re still very good, generally speaking,” he said. “Equity is still strong even with lower income. Farmland values are strong. There is still available cash for investment.”

One concern he has moving forward is that younger producers have not experienced downturns previously, and the increase in interest rates the past two years has squeezed their bottom lines.

The analysis was produced in collaboration with Kansas State Agricultural Economics, University of Arkansas Research and Extension and the Center for Agricultural Profitability in the Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources at the University of Nebraska.

Snapshot of states

Missouri

Missouri net farm income is projected to decline to $3.6 billion in 2024, continuing a downtrend from record-setting farm income levels in 2022. From 2023 to 2024, crop and livestock receipts are expected to decrease by a combined $1.6 billion. Driven by lower feed and fertilizer costs, production expenses are expected to decrease by $700 million.

Missouri’s projected 18% decrease in net farm income is smaller than the projected 25.5% decrease in U.S. net income for 2024. Missouri’s net farm income is projected to increase in 2025 and 2026 with net farm income average of $3.7 billion across the 10-year baseline.

Kansas

Kansas net farm income is projected to reach $2.9 billion in 2024, a small decrease from 2023 as assumed average weather increases crop receipts despite lower market prices. From 2023 to 2024, crop and livestock receipts are expected to increase by $600 million as yields recover and cattle prices increase.

Driven by lower feed and fertilizer costs, production expenses are projected to decrease by $700 million. Kansas’ projected 21% increase in net farm income is significantly different from the projected 25.5% decrease in U.S. net farm income due to the state’s drought recovery and higher cattle prices. Kansas net farm income is projected to increase in 2025 and 2026, due largely to favorable cattle markets, lower expenses and a return to normal yields for major crops. The net farm income is an average of $3.7 billion across a 10-year baseline of 2022 to 2032.

Arkansas

After record-setting farm income in 2022, Arkansas saw a backpedal in 2023 that is projected to extend into 2024 with another $500 million decline in net farm income. Cash receipts are estimated to decline by $800 million as many crop and livestock prices are projected to move lower in 2024.

Production expenses are projected to offer some relief with nearly $600 million in decline as feed and fertilizer move lower. Although net farm income has declined from record levels, estimated 2024 levels are still higher compared to 2021. Arkansas’ projected 15% drop in net farm income is smaller than the forecast of a 25.5% decrease in U.S. net farm income for 2024.

Arkansas will see a farm receipts decline by $800 million offset by a $600 million decline in production expenses, which led to a drop in projected net farm income. Despite the decline from 2023 to 2024, Arkansas net farm income remains higher than the 2015 to 2022 historical average. Arkansas’ net farm income is projected to slowly climb to an average of $3.3 billion across the 10-year baseline.

Nebraska

Nebraska net farm income took a fall in 2022 before partially rebounding in 2023. The first projections for 2024 point to a sharp decline in Nebraska farm income that was consistent with national trends. Crop receipts fell in 2023 on lower prices and look to fall further in 2024. Livestock receipts grew in 2023 on the strength of cattle prices but look to decline in 2024 with reduced cattle marketings and further declines in other livestock commodities.

Production expenses that persisted higher through 2023 appear to offer some relief in 2024. A projected farm income of $6 billion for 2024 would be down from the past three years but would be strong relative to the past decade. Nebraska’s net farm income is expected to average $6.3 billion across the next decade.

Dave Bergmeier can be reached at 620-227-1822 or [email protected].