With more moisture in much of the western United States, the wheat industry appears to be off to a pretty good start for 2024 and remains the No. 1 food grain produced in our nation. But when you look at some of the longer term trends, there may be cause for alarm.

That’s the perspective of Chandler Goule, who’s been serving as CEO of the National Association of Wheat Growers for the last eight years.

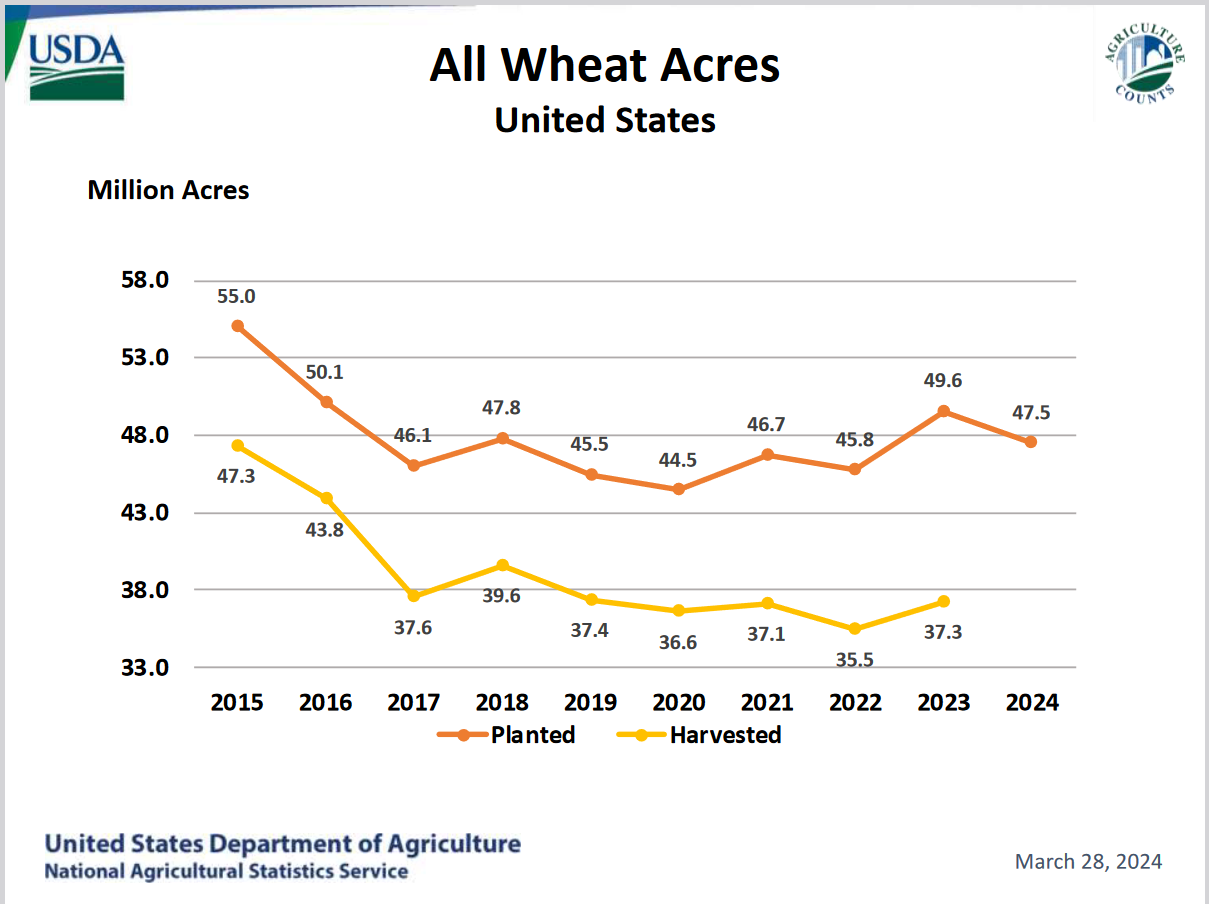

“We have seen a steady decline in wheat acreage for the last 10 years and definitely in the last 20 years,” Goule noted in a recent Open Mic interview. He said the number of U.S. wheat farmers has dropped from about 170,000 in 2002 to 97,000 in 2022.

Other factors

Goule attributes the decline in farmers and acres to several factors, including the genetic modifications that have enabled corn and soybeans to be grown all the way north to the Canadian border. Historically, the wheat industry has stayed away from using some of the same innovations that could lead to higher yields and drought tolerance because of customers’ concerns over genetic modification in a food crop.

“Twenty-five years ago, we didn’t have 72-day corn and we didn’t have corn growing in northern Minnesota and North Dakota and on up there in Montana. Now we do because both corn and soy have the ability to take advantage of innovation and gene technology. They are able to produce more hybrids that can grow not only in in colder climate climates but drier climates, and when they have a wider margin and a wider basis, they are slowly starting to creep into what has always predominantly been cereal grain areas like wheat, barley, and canola. We are becoming less competitive economically with other commodities that are able to adopt innovation and because wheat is a food grain, we are slowly being left behind.”

Disincentives, too

However, he also pointed to several government programs that could also disincentivize wheat production, at least compared to the economics of planting other crops. Goule says wheat industry partners are already expressing concerns about the availability of wheat acres and how U.S. growers can continue to produce enough wheat to fill domestic contracts and also to fulfill existing export contracts.

Goule says corn or soybean farmers might be questioning the Biden administration’s push for electric vehicles, but still see opportunities for ethanol and biodiesel, plus, there’s this “huge frontier called sustainable aviation fuel” that could be the opportunity for those crops and more to participate.

“The National Association of Wheat Growers fully supports renewable fuels and we support a sustainable aviation fuel. What I’m worried about is the unintended consequences of what this will do to the wheat industry,” he said.

New markets needed

Without some type of new incentives or markets for wheat production, Goule says the SAF demand could also put crops like camelina in direct competition with wheat acres in the West and canola could possibly replace typical wheat rotations east of the Mississippi River.

“I’m worried that we’re going to slowly end up pushing the wheat industry out of the United States, very similar to what happened to the oat industry, which basically is 100% up in Canada. I’m just kind of sounding the alarm here.”

Of course, there will be some stiff “climate-smart” growing requirements for corn and soy to be eligible for the SAF market and it’s not clear how much acreage will be eligible. But one of the requirements is to plant cover crops and that also puts wheat at a comparative disadvantage compared to government incentives available for other crops. USDA’s Risk Management Agency does not consider winter wheat to be a cover crop because—despite the ability to cover the soil and sequester carbon—it’s harvested a few months later.

“If you think back about two years ago, USDA came out with the cover-crop program and they were going to pay you $25 an acre to plant a cover crop. And then I called USDA and said, ‘Well, this is great, but 70% of the wheat production in the United States is winter wheat, and we were completely disqualified from participating in that program because we harvest our wheat and it’s considered double dipping.’”

Participation important

Goule says that is, unfortunately, another example of how the wheat industry is being left behind because of the inability to participate in those USDA programs.

He has brought this issue up directly to Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack and other government officials.

“He knows about the situation and I know he’s concerned about it,” Goule said. But overall, “I don’t think people are thinking about the unintended consequences of what they’re doing to the largest food grain industry in the United States.”

Editor’s note: Sara Wyant is publisher of Agri-Pulse Communications, Inc., www.Agri-Pulse.com.