On Sept. 11, Francine became the third and strongest hurricane of the season to strike the U.S. Gulf Coast, following Beryl (in Texas) in early July and Debby (in Florida) in early August. Francine briefly achieved sustained winds near 100 mph while making landfall around 5 p.m. in Louisiana’s Terrebonne Parish.

Hurricane-force wind gusts (74 miles per hour or higher) spread as far inland as New Orleans, where a gust to 78 mph was clocked at Louis Armstrong International Airport. Meanwhile in the Mississippi Delta, antecedent dryness minimized flooding, although rainfall topped 4 inches in many locations and localized wind gusts briefly topped 50 mph. As the former hurricane drifted farther inland, days of locally heavy showers led to pockets of flash flooding, extending as far east as Alabama and the Florida Panhandle.

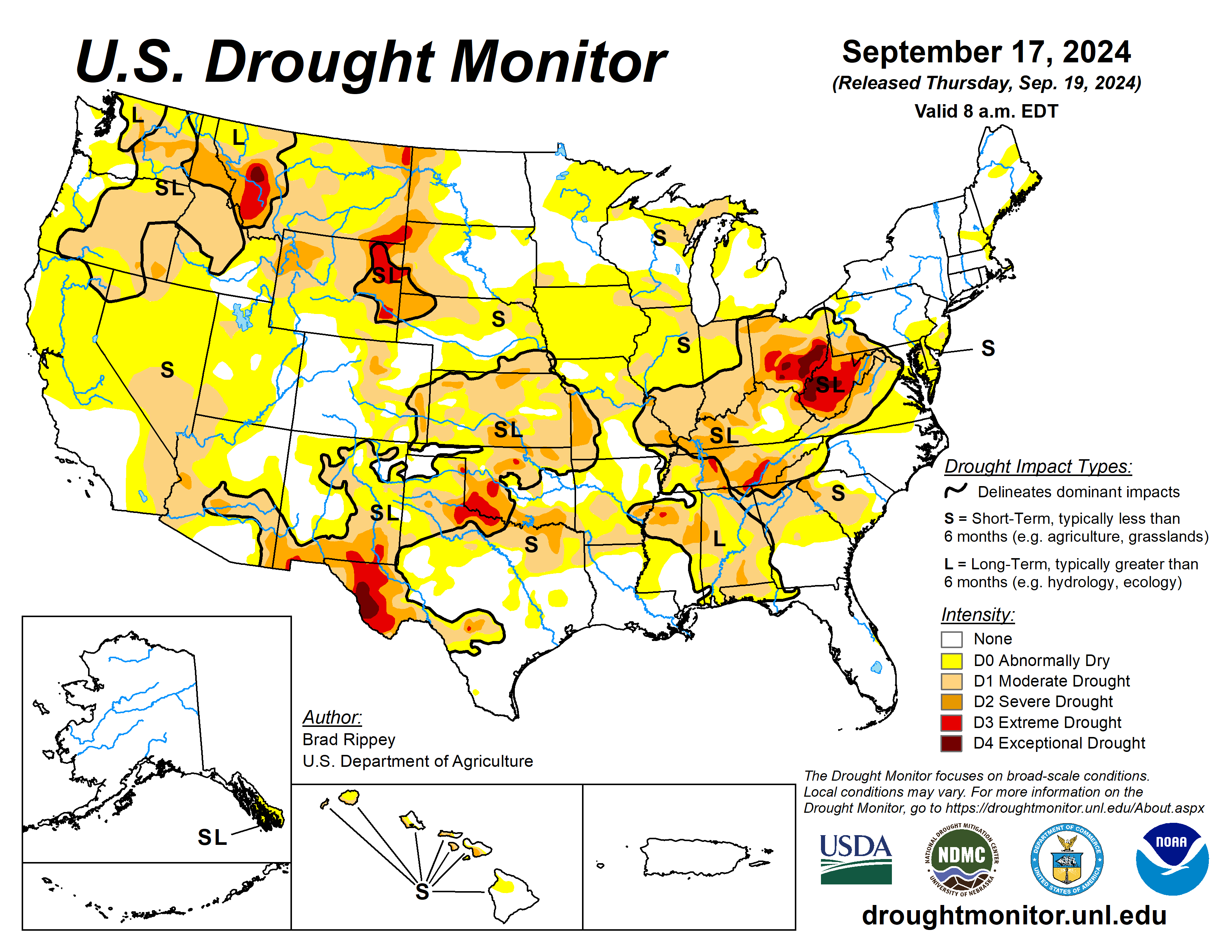

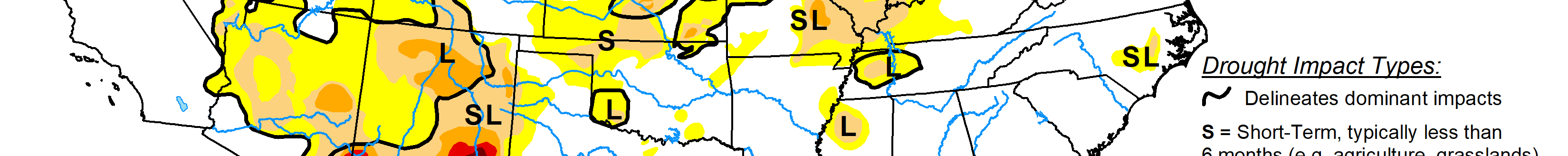

Less than a week later, on Sept. 16, Potential Tropical Storm Eight moved ashore in northeastern South Carolina and delivered flooding rainfall (locally a foot or more) across southeastern North Carolina. By the morning of Sept. 17, the end of this drought-monitoring period, much of North Carolina and portions of neighboring states had received significant rain. The remainder of the country largely experienced dry weather, leaving widespread soil moisture shortages across the Plains and Midwest—a classic late-summer and early-autumn flash drought.

In the western U.S., a cooling trend was accompanied some rain and high-elevation snow, heaviest across the northern Rockies and environs. As the long-running Western heat wave subsided, late-season warmth replaced previously cool conditions across the Plains, Midwest, and Northeast. Nationally, nearly one-half (46%) of the rangeland and pastures were rated in very poor to poor condition on Sept. 15, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, up from an early-summer minimum of 19%.

The U.S. Drought Monitor is jointly produced by the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration. (Map courtesy of NDMC.)

South

Hurricane Francine delivered heavy rain across much of Mississippi, as well as parts of Arkansas, Louisiana, and Tennessee. On Sept. 11, daily-record totals included 7.33 inches in New Orleans, Louisiana, and 4.14 inches in Gulfport, Mississippi. For New Orleans, it was the second-wettest September day on record, behind only 7.52 inches on Sept. 25, 2002. Elsewhere on Sept. 12, daily-record totals reached 4.22 inches in Memphis, Tennessee; 3.95 inches in Jonesboro, Arkansas; and 3.05 inches in Tupelo, Mississippi.

A separate area of heavy rain, prior to Francine’s arrival, soaked a small geographic area in southeastern Oklahoma, northeastern Texas, and southwestern Arkansas. However, areas outside the range of these downpours largely experienced worsening drought conditions. On Sept. 15, Oklahoma led the region with topsoil moisture rated 61% very short to short, followed by Texas at 54%. Meanwhile, Texas led the region with rangeland and pastures rated 48% very poor to poor, followed by Oklahoma at 35%. On that date, Texas led the country with 36% of its cotton rated very poor to poor, well above the national value of 26%.

Several patches of extreme drought continued to affect key agricultural regions of both Oklahoma and Texas. In Texas’ northern panhandle, record-setting highs for Sept. 13 included 102 degrees Fahrenheit in Borger and 101 degrees in Amarillo. For Amarillo, it was the latest triple-digit reading on record, supplanting 101 degrees on Sept.11, 1910. Both Borger at 101 degrees and Amarillo at 100 degrees logged triple-digit, daily-record highs again on Sept. 14. Several patches of extreme drought continued to affect key agricultural regions of both Oklahoma and Texas.

Midwest

The Midwest experienced rather uniform drought deterioration, with up to one category changes observed. Although the warm, dry weather favored corn and soybean maturation, depleted soil moisture reserves remained a significant concern for pastures, immature crops, and recently planted winter grains.

On Sept. 15, Midwestern topsoil moisture rated very short to short ranged from 25% in Minnesota to 92% in Ohio. In the hardest-hit drought areas, other complications included abysmal streamflow and surface water shortages. Low-water concerns extended into the lower Mississippi Valley, largely due to lack of runoff in recent weeks from the Ohio Valley.

High Plains

Warm, mostly dry weather led to general expansion of abnormal dryness and various drought categories.

Across the six-state region, topsoil moisture rated very short to short on September 15 ranged from 30% in North Dakota to 80% in Wyoming. In fact, values were above 50% in all states, except North Dakota.

Some of the worst conditions—extreme drought—existed across northeastern Wyoming and southeastern Montana, an area still recovering from last month’s Remington and House Draw Fires, which collectively burned across more than 370,000 acres of vegetation, including rangeland. Wyoming led the region on Sept. 15 with 70% of its rangeland and pastures rated very poor to poor, followed by Nebraska at 45% and South Dakota at 42%.

West

Despite widespread precipitation in the northern Rockies and environs, only slight drought improvement was introduced, as concerns related to poor vegetation health and water-supply shortages were ongoing. In one piece of good news, however, a summer-long western heat wave effectively ended. On Sept. 17, the maximum temperature of 93 degrees in Phoenix, Arizona, halted a record-setting, 113-day streak (May 27 to Sept. 16) with afternoon readings of 100 degrees or greater.

Given the turn toward cooler weather and the gradual increase in cool-season precipitation, the wildfire threat has diminished in some areas. In southern California, however, the Airport, Bridge, and Line Fires collectively burned more than 115,000 acres of vegetation earlier this month.

On Sept. 15, topsoil moisture in agricultural regions ranged from 54 to 80% very short to short in eight of 11 western states—all but California, Arizona, and Utah. Similarly, rangeland and pastures were rated 40 to 70% very poor to poor in eight Western States—all but California, Utah, and Colorado.

Looking ahead

During the next five days, active weather across the nation’s mid-section could lead to significant precipitation in from the central sections of the Rockies and Plains into the upper Midwest. While rain could slow agricultural fieldwork, including harvest activities, rangeland, pastures, and recently planted winter wheat will benefit from a boost in topsoil moisture.

In contrast, generally dry weather will prevail across the remainder of the country, excluding the Atlantic Coast States. However, the western Caribbean Sea will need to be monitored for tropical cyclone development, with possible future implications for the eastern U.S.

The National Weather Service’s 6- to 10-day outlook for Sept. 24 to 28 calls for of near- or above-normal temperatures nationwide, with the West, north, and southern Texas having the greatest likelihood of experiencing warmer-than-normal weather. Meanwhile, near- or below-normal precipitation across the western and north-central U.S. should contrast with wetter-than-normal conditions from the central and southern Plains to the Atlantic Coast, extending as far north as the Ohio Valley and southern New England.

Brad Rippey is with the U.S. Department of Agriculture.