Violent storms dominated the weather headlines

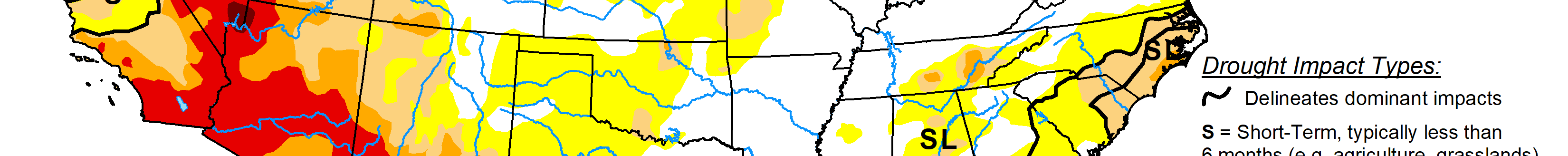

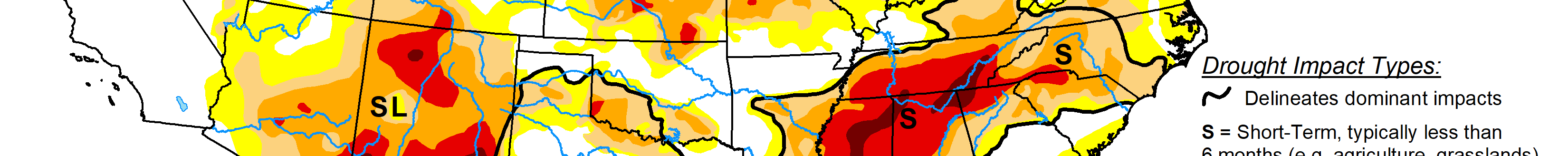

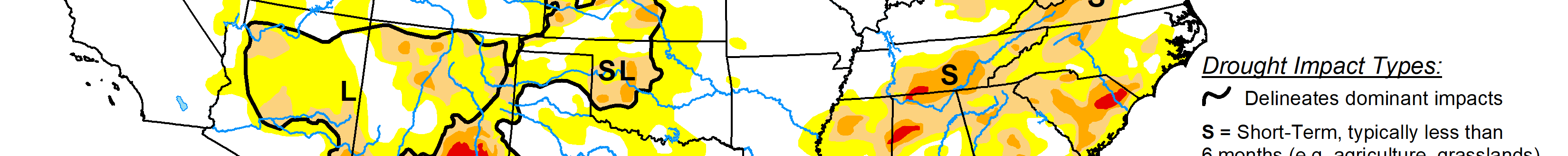

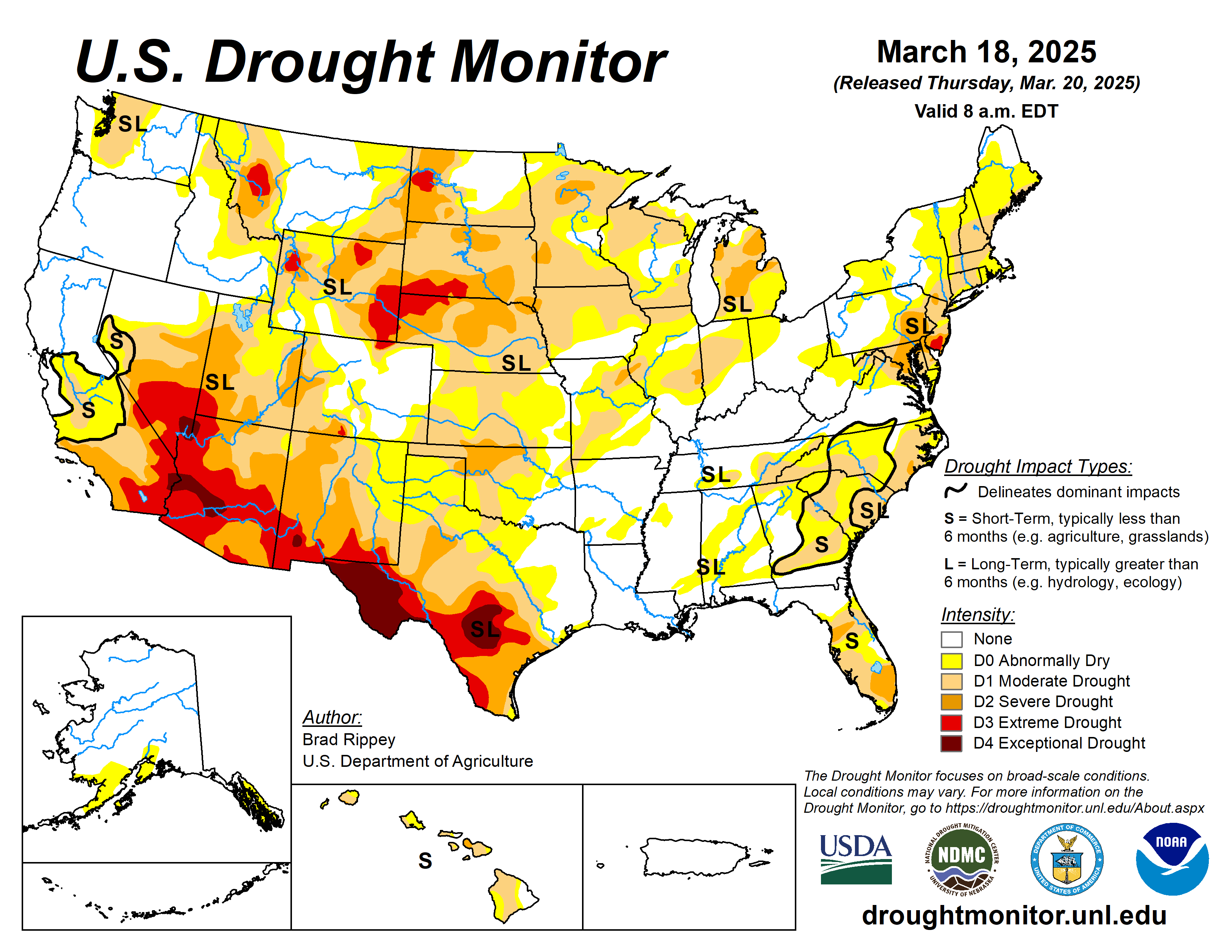

For the drought-monitoring period ending the morning of March 18, significant precipitation fell in parts of the eastern and western United States, while warm, dry, windy weather worsened drought across portions of the central and southern Plains and neighboring regions.

In recent days, major spring storms have fueled an extraordinarily active period of U.S. weather, featuring high winds, blowing dust, fast-moving wildfires, severe thunderstorms, torrential rain, and wind-driven snow. Some locations experienced multiple hazards within hours, or even simultaneously.

High winds and blowing dust were especially severe across the southern High Plains and parts of the Southwest on March 14 and 18, with some locations reporting wind gusts topping 80 mph and visibilities of one-half mile or less. In Oklahoma alone, mid-March wildfires tore across at least 170,000 acres of land and destroyed more than 200 residences.

Farther north, wind-blown snow affected portions of the central Plains and upper Midwest, mainly on March 15—and again on March 19 to 20, early in the new drought-monitoring period. Meanwhile, a severe weather outbreak from March 14 to 16 spawned nearly 150 tornadoes from the mid-South into the eastern U.S., based on preliminary reports from the National Weather Service.

Early reports indicated that the extreme weather resulted in dozens of fatalities, with causes of death ranging from wildfires to tornadoes to chain-reaction collisions. Elsewhere, occasionally heavy precipitation locally trimmed drought severity, with some of the most extensive improvement occurring in the Southeast.

The U.S. Drought Monitor is jointly produced by the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration. (Map courtesy of NDMC.)

South

Dire conditions have developed in recent days across the Southern Plains, where any benefit from last November’s record-setting rainfall is quickly diminishing. During major dust storms on March 14 and 18, wind gusts in Lubbock, Texas, were clocked at 82 and 78 miles per hour, respectively. The March 14 gust was a spring (March-May) record for Lubbock—and marked the highest non-convective gust on record in that location.

As the dust blew on March 14, numerous wildfires raged in Oklahoma, as well as neighboring areas in southern Kansas and the northern panhandle of Texas. The dusty scene was repeated on March 18, with visibilities as low as one-quarter to one-half mile widespread across western Texas.

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, statewide topsoil moisture in Texas was rated 71% very short to short on March 16, while 71% of the rangeland and pastures were rated in very poor to poor condition. For the week ending March 18, broad expansion of all drought categories was noted in Oklahoma and Texas. Farther east, however, heavy rain led to large reductions in the coverage of dryness and drought in much of Tennessee.

Midwest

Starting March 14, parts of the lower Midwest were affected by rain and severe weather, which improved the drought situation in Illinois, Indiana, and southern Michigan. Meanwhile, snow in Minnesota led to some targeted drought improvement.

In contrast, large sections of Missouri were bypassed by significant rainfall, leading to increases in coverage of abnormal dryness and moderate to severe drought.

High Plains

Significant changes were largely limited to Kansas, where expansion or introduction of dryness and moderate to severe drought resulted from mostly warm, dry, windy weather.

By March 16, the U.S. Department of Agriculture indicated that statewide topsoil moisture in Kansas was rated 47% very short to short. Elsewhere, some drought improvement was introduced in central Wyoming, largely based on favorable snowpack observations.

West

Although meaningful precipitation extended into the Southwest, snowpack deficits are so significant that any improvement in the overall drought and water-supply situation has been extremely limited.

Additionally, harsh winds across the lower Southwest have led to extensive blowing dust in recent days, particularly across the areas of southern New Mexico experiencing severe to exceptional drought.

Looking ahead

A low-pressure system moving into eastern Canada on Thursday will drag a cold front through the eastern United States. Locally severe thunderstorms may affect the middle Atlantic States on Thursday, followed by widespread Northeastern precipitation—rain and snow—lingering through Friday.

Meanwhile, conditions across the nation’s mid-section will improve, following Wednesday’s blizzard from the central Plains into the upper Midwest and a widespread high-wind event. Still, an elevated wildfire threat will persist at least through Friday in parts of the south-central U.S., including the southern High Plains. Farther north, a pair of Pacific disturbances will move eastward near the Canadian border.

The initial system will be fairly weak, but the second storm will intensify during the weekend across the northern Plains and upper Midwest. Impacts from the latter system, which will persist into early next week, should include late-season snow from the Cascades to the Great Lakes region; another round of windy weather across the nation’s mid-section; and potentially severe thunderstorms across portions of the South, East, and lower Midwest.

The National Weather Service’s 6- to 10-day outlook for March 25 to 29 calls for the likelihood of near- or below-normal temperatures in most areas from the Mississippi River eastward, while warmer-than-normal weather will broadly prevail from the Pacific Coast to the Plains.

Meanwhile, near- or above-normal precipitation across much of the country should contrast with drier-than-normal conditions in the Southeast, excluding southern Florida, and an area stretching from the Four Corners region to the central High Plains.

Areas with the greatest likelihood of experiencing wetter-than-normal weather include southern Texas and the Pacific Northwest.

Brad Rippey is with the U.S. Department of Agriculture.