What is New World screwworm, and why are they dangerous?

New World screwworm has dominated livestock news for much of the past year, and although confirmed cases and U.S. Department of Agriculture’s plan to eradicate this problematic pest have been thoroughly covered, the actual insect is still a mystery to many.

In a recent webinar, Sonja Swiger, Extension entomologist at Texas A&M University, spoke about NWS, its history and life cycle.

“They get that screwworm name because they have this odd screw-like appearance, being that their body segments are covered in little spines,” Swiger said. “They actually feed with their heads down, which is their mouth hooks, and they basically burrow into the tissue, kind of like a screw being screwed into wood.”

She said there are actually two species of fly that are referred to as screwworms.

“The one we’re really worried about right now is what we call cochliomyia hominivorax, which is NWS,” she said. “The other species is known as the secondary screwworm, and it’s called cochliomyia macellaria. Both are blowfly species that are slightly larger in size in comparison to a normal house fly.”

The two species have subtle differences in appearances, but the larger differentiator between them is the time they arrive at the host. NWS larvae infest the living tissue of warm-blooded animals—livestock and wildlife—in particular. Swiger said NWS can also infest pets, birds on rare occasions, and even humans. NWS can cause serious injury to livestock and if left untreated, animals can die from infestation. Secondary screwworm is much less concerning because it only comes to the scene after the host is deceased and utilizes the carcass to lay its eggs.

History of NWS

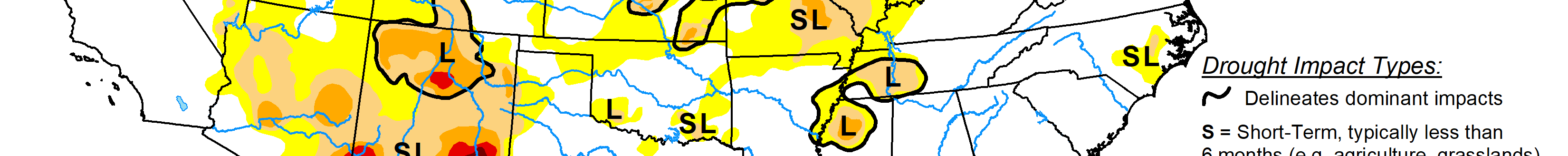

Although NWS has not been a common subject until recent years, it is not new to North America. Swiger said it was first recognized in the southwestern part of the United States in 1842 and received its name in 1858 when it was finally named as cochliomyia. In the 1930s, NWS were able to expand their territory in the U.S. Swiger said there was a severe drought in Texas and some other areas where cattle were kept, and cattle had to be moved to the Southeast to allow them to finish out the growing process.

That process also relocated the flies with them, so they were able to expand into the southeastern half of the U.S. Swiger said in the mid to late 1930s, scientists started to do more research on this fly, because they had realized the impact it was having, and it needed to be controlled.

“They needed to learn how to grow it into large numbers in order to figure out how to control it, which sounds a little weird, but that’s kind of how the process goes when dealing with insects,” she said.

During this time, researchers came up with the sterile insect technique, a method of pest control that involves releasing sterilized insects to reduce or eradicate populations. That strategy is currently in use right now to decrease populations of NWS. Research efforts continued through the 1950s, with some delays due to World War II. In 1954, the eradication of NWS with sterile flies officially began. It took years, but the flies were slowly eliminated throughout the U.S. and Mexico.

“By 1967, we had finally gotten numbers down pretty low—less than 1,000, which was a 99% reduction,” Swiger said. “But a few years later, due to numbers staying high in Mexico and mild winters, there was a severe outbreak in Texas and neighboring states. There were up to 96,000 cases, and that caused them to have to start producing many sterile flies to get that back under control.”

In the late 1970s, scientists develop other methods to assist with the sterile male techniques and opened another sterile fly production plant in Mexico. However, in the late 1980s NWS was reintroduced in Florida via dogs that were being brought to the U.S.

Progress continued, and by 1991, NWS in Mexico had been eradicated. In 1994, the Panama-United States Commission for the Eradication and Prevention of Screwworm, or COPEG, was formed and is still operating today.

“When this program was developed, they set up a permanent biological barrier, which is at the Darién Gap in Panama,” Swiger said. “And they finally were able to successfully eradicate the fly from the entire western half of Panama, all the way up into Mexico. So, we now had the U.S., Mexico, Central America, Panama, and the western half of the Darien Gap completely successfully eradicated.”

Since that time, the only disease resurgences have been the minor 2016 outbreak in the Florida Keys in key deer and the current outbreak that is believed to have begun in 2023 and is ongoing.

NWS preferences and life cycle

NWS can find environments to thrive from the southern parts of Canada, and across North, Central and South America. Swiger said they generally prefer climates between 64 to 91 degrees Fahrenheit, with peak activity occurring around 86 degrees. When temperatures fall below 59 degrees Fahrenheit, they have little to no activity.

Swiger said NWS can range farther north during the summers, but they will retreat in the wintertime. She said they thrive in areas with heavy rainfall, but that does not mean these conditions are required for them to be present. They are a daytime active species with little to no activity at night, and they do not do well in windy conditions.

NWS prefers tropical forests and wooded areas, but they will seek hosts in pastures or fields where animals are located. Swiger said they are usually found in clusters and not evenly distributed throughout an area. She said the life cycle from egg to adult for NWS takes about four weeks.

“The screwworm eggs are laid by the female directly into or on a wound that they find on an animal,” Swiger said. “But they can also use exposed mucous membranes to lay their eggs. They need an area that has a little bit of moisture and is a direct opening for their larvae to get into that animal. Those eggs will be laid in groups of about 200 to 300 at a time, and they will start to hatch.”

However, multiple flies can lay eggs in one wound, increasing the number of eggs to the 1,000s. Swiger said the eggs will hatch out within 10 to 12 hours, and the larvae that come out will start to feed on living tissue and cause severe damage and feed on larger amounts of flesh as they grow.

“They’ll stay in that tissue until they’ve fully consumed enough food to allow them to pupate and move into that next life stage,” she explained. “If the infestation is severe, and they’re left in there and not treated and removed from that animal, they can kill that animal. The infestation can get to an area that effects the vital organs of the animal.”

Additionally, Swiger said some infestations are in the head of the animal, creating a direct route into the brain. NWS are known to give off a distinct foul odor that is an attractant to other females to lay their eggs in the host. After five to seven days, larvae are finished feeding and will detach for the host and go into the ground to pupate again.

“They can last about five to seven days on their own, and then they will hatch back out into adults, and start that cycle all over again,” Swiger said.

To report a suspected case of NWS, contact your local or state veterinarian.

Lacey Vilhauer can be reached at 620-227-1871 or [email protected].