Jimmy Emmons —‘Mr. Soil Health’ —a lifetime commitment to conservation

When you meet Jimmy Emmons, you will be shaking a hardworking hand and you will feel the warmth of that unique smile coming from under his wide-brimmed cowboy hat. It’s a moment that you will never forget because you have shaken hands with a true living legend. His close friends call him “Mr. Soil Health”. It’s a title he deserves.

Ever since the “Dust Bowl” followed by the drought of the 1950s, conservationists have tried many successful and unsuccessful methods to save the soil and keep it from blowing away again. It has seemed engrained to “old timers” that we had to turn the soil, often with a moldboard plow. Even after the “Dust Bowl”, which demonstrated the fallacy of the plow, it was still part of our nature.

It has taken time to change. The stubble mulch plow, which left the stubble on top of the ground, was one of the first efforts. It worked well in many cases, but after two or three years, many producers couldn’t stand not having a clean field to sow the seeds, so we plowed it up. No-till came later. We killed the weeds with chemical, fertilized to high heaven and harvested what it grew. The more it rained the more we fertilized and the more it grew.

Then came Emmons. With his roots deep in Dewey County, Oklahoma, near Leedey, his efforts stood out among a handful of soil heath pioneers. Emmons studied his land, his crops, his livestock, and he carefully watched everything that happened and diligently kept records on the cost of every single item. He figured out his soil was becoming unhealthier with every growing season. He and his wife, Ginger, had begun farming in the conventional way. It became evident their costs were going up. The price of machinery, repairs, fuel, feed, seed, fertilizer, and chemicals were increasing, but their income was not keeping up, in fact sometimes going down. Something had to change.

A family visit

My wife and I had the opportunity to spend an afternoon with Jimmy and Ginger, and they shared their experiences and how, through soil health and regenerative agriculture, they have brought success to their operation. To best share the conversation we had that afternoon, questions and answers are shown in the following paragraphs.

Q. Next year, parts of your ranch will be in your family for 100 years. Would you give a short history of your land, how it was when you took over, and the events that caused you to identify soil health as a primary concern for keeping your ranch sustainable?

A. My great-granddad brought my granddad to the farm in 1926. He helped granddad rent the farm for three years. My granddad bought the farm in the spring of 1934. Somehow, despite the stock market crash, the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl, he was able to pay for the land in eight years. He had two boys and one girl. Both the boys (My Dad and his brother) had a hired hand apiece. By working day and night, they were able to farm 1,000 acres with two old John Deere tractors.

The farm included a large field with some of the best land in Dewey County. My granddad took a walking plow in early 1934 and made a cut (furrow) along the field. Then in April 1934, the unthinkable happened. The area received 14 inches of rain in a short time. It was called the Hammon flood and the furrow that granddad had made across the field became a creek overnight and it is still there today. Had he not done that, we would have lost the topsoil on the entire field.

In 1995, we started no-till, but by the early 2000s we knew something was missing or not right. The soil was getting harder, not mellow. I was impressed by a presentation that I heard David Brandt give at the National Association of Conservation Districts annual meeting on cover crops. I reached out to the Natural Resources Conservation Service, the Noble Foundation, the Oklahoma Conservation Commission, the Oklahoma Association of Conservation Districts, and the Dewey County Conservation District. Because of the need to gather information, we became a “Demo Farm”.

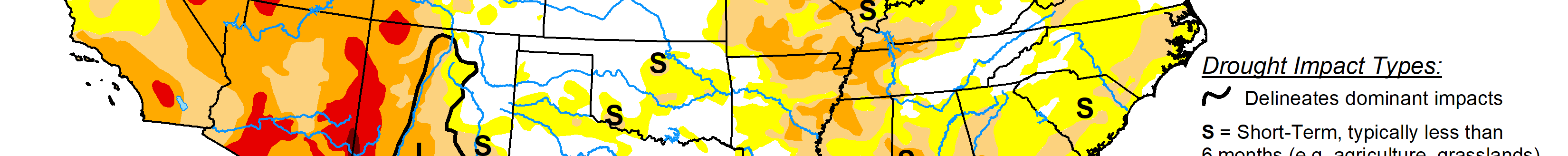

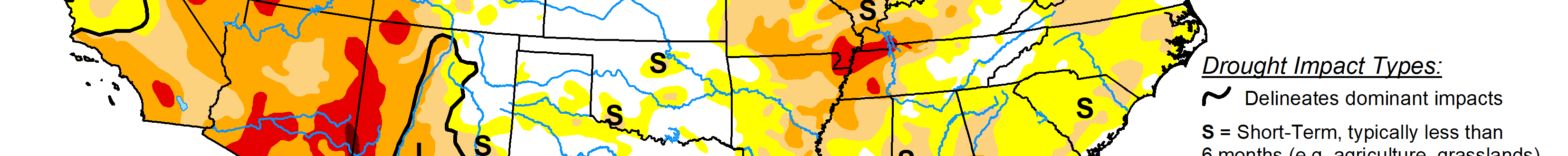

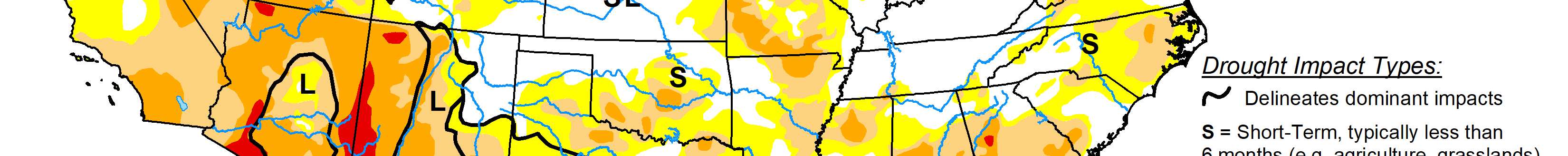

Using cover crops, keeping something growing on the land year-round, reducing tillage, and paying close attention to what was happening to our soil began to pay off. In 2010, 2011 and 2012, during an extended heat and drought period, it became evident that we were headed in the right direction.

Q. Do you still plow any of the soil? How long has it taken you to transform from conventional tillage to your present operation and do you use any chemicals or commercial fertilizers?

A. We have been using cover crops for about 15 years. We occasionally use chemicals for a burn-down or to kill invasive species. We use 60 to 70% less chemicals than when we were farming conventionally. We use very little fertilizer. We tried some fertilizer on wheat last year in a trial program and the results showed that we could have done just as well without it. We no longer till the soil, except in cases where feral hogs tear up the ground and we must level the ground. Feral hogs are a serious problem in this area.

Our soil infiltration rate has improved significantly. We have learned that by cover cropping we have plant residue on the surface whenever it rains resulting in less runoff, along with several other positive factors. In times of rain, we farmers ask our neighbors, “How much rain did you get?”, but perhaps the question should be “What did your soil do with the rain you got?

Q. I notice that you have collars or halters on your cows. How do these work and what kinds of information can you get from them? Will they help you find a missing animal?

A. These are Halter brand collars invented by a New Zealand company. They have solar panels on each side of the collar behind each ear, and they typically last five to six years. A tower is installed on the ranch and data from the cows can be accessed from your phone or computer through signals from the tower. Missing animals can be located easily.

Q. What is virtual fencing?

A. Virtual fencing goes hand in hand with the halters and system just described. I think of virtual fencing as being a fence that can be drawn on a map. Using the 30-foot tower and the collars, you establish the size of the area you want to graze and the boundary.

As the cows approach the virtual fence boundary, they will receive a signal, which is a beep and or a vibration. If the cow continues and gets too close to the boundary, the collar delivers a small electric shock.

Using this technology allows us to monitor feed and water supply to the cattle, and we can go feed when we need to, not when we think we should. We can move cattle easily, and create new pastures, which allows us to use intensive grazing techniques. We can even determine the amount of forage that has been grazed while the cattle have been in a certain pasture.

Q. In 2018, a huge wildfire went across part of your ranch. What did you do to help the land recover and bring in back into production?

A. We deferred grazing on the land for one year. Additionally, we mulched the skeletons of the trees, which made a carbon rich bed for the re-growth of the grass to occur. It worked well.

Q. Now that you have been using soil health and regenerative agriculture practices for several years, how has this affected your bottom line?

A. Using soil health practices, cover crops, and all that goes along with it, the results have been significant. Our fuel bill is down over $200,000 a year. Depreciation, wear and tear on equipment, and repair costs are almost gone. We have less trips over the land with less equipment to break down. Our chemical costs have been reduced by 70%, our soil organic matter has increased from 0.5% to 3.5%, and our soil infiltration rate has increased, meaning that we are able to use the rain more efficiently.

By using virtual fences, we can graze intensively, and don’t have the huge expense of building permanent fences. I am noticing that our cattle often bite off the top 2 or 3 inches of grass and move on. This is exactly what we would hope for, and it allows the grass to recover more quickly.

Q. In the last few years, you have received several significant awards and served as president of the Oklahoma Association of Conservation Districts. Which of these awards are the most meaningful to you?

A. I believe the Leopold Award in 2018 was a highlight. Leopold was a soil health genius and to receive an award named after him served as verification of the work that we are doing. Jay Fuhrer, renowned soil health expert, a 40-year USDA-NRCS conservationist, and lead educator at the Menoken Conservation Farm in Menoken, North Dakota. said,” I have been to Jimmy Emmons’ place and put a spade in his soil. He is the real deal!”

Q. What advice would you give to beginning farmers just out of school? (Both Jimmy and Ginger expressed concern that there are only a limited number of young people interested in farming and ranching as their life’s work.)

A. We need to share with them the lessons that we have learned over the last 100 years. We have knowledge and tools now that we didn’t have years ago. We don’t have to do it the way we have always done it. If a young person can acquire land, using soil health principles can greatly reduce the initial machinery costs, chemical, fertilizer, and other costs, and provide the opportunity to become profitable more quickly.

When asked if he had any other comments, Jimmy said, “We are taught that we should take care of the land while we are on this Earth, and that we must be good stewards of the soil. In a way, this has become a spiritual mission that has driven me to learn about soil health practices, share with others, and leave the land better than I found it.”

There is one more part to the story—Jimmy Emmons was sworn in as assistant chief, U.S. Department of Agriculture-Natural Resources Conservation Service on May 19, in Washington.

Tom Lucas can be reached at (580) 727-4397 or [email protected].