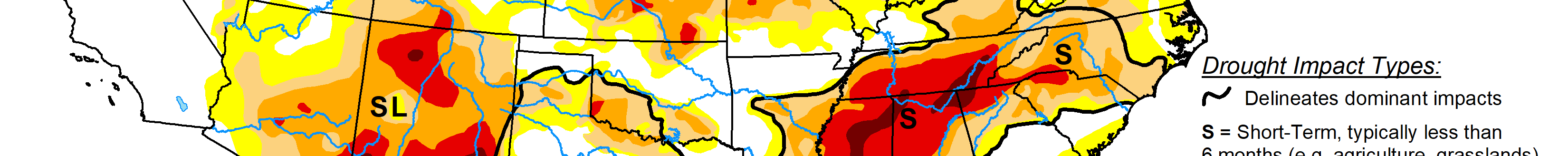

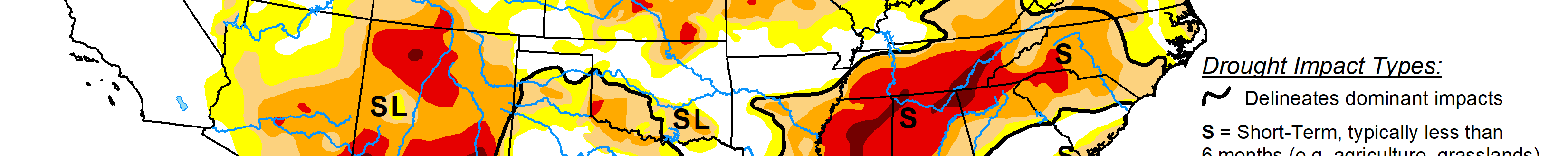

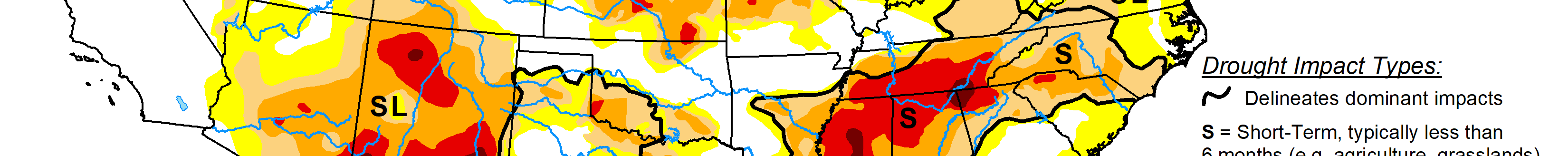

Drought has plagued the Great Plains, and southeastern states were ravaged with hurricanes and tornadoes. Early this year, a Florida rain deluge was measured in feet per hour, not inches, and now the spring thaw is overflowing the Mississippi River valley.

These swift weather changes can be perplexing to farmers tasked with feeding the world and keeping operations in the black.

Welcome to another new normal, and a bin full of challenges.

Researchers in the western United States are studying “directional changes and extremes in climate and working with farmers and ranchers to help them incorporate adaptive management and flexibility into their operations,” said Justin Derner, a supervisory research rangeland management specialist for the U.S. Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Service based in Cheyenne, Wyoming.

Derner joined a number of USDA and Colorado State University experts in co-writing a paper entitled “Practical Considerations for Adaptive Strategies by US Grazing Land Managers with a Changing Climate.”

The work was first published in a special issue of the scientific journal Agrosystems, Geosciences and Environment and the full study is available online at bit.ly/44QF4kb.

“We wanted to write it to provide producers with viable tools and strategies they could use now, to deal with the current consequences of this climatic variability,” he said.

Simplified, the approach contains “two big buckets,” Derner said. One (bucket) illustrates the options producers have by way of diversifying their crop and livestock systems. The recipe includes “changing the number and types of animals given weather and seasonal climate changes, thereby reducing risk for producers,” he said. Education fills the second bucket.

“It’s learning about uncertainty, being able to share that with each other, learn from experiences, and develop management plans for locally relevant context,” he said.

In short, producers need “a template for what is currently unknown,” Derner said. “We’ve had some pretty drastic short-term droughts. What can producers learn from that?”

Mindsets have changed.

With much of the Plains suffering from a lack of precipitation and other untimely banes, producers need a suite of options for effective stewardship of natural resources.

How soon do producers need to know in order to reach timely conclusions?

“That’s the 64-million-dollar question,” Derner said. “For most ranchers in the Great Plains, early spring is a key decision time, or trigger, regarding how many grazing animals will be needed to match the available forage that is expected.”

As ranchers develop a menu of options for adaptively managing their grazing and resources, a series of questions can provide insight:

- Do you have another place to go if it’s dry at your ranch?

- Is alternative feed available, or could you take livestock to a feed yard?

- What’s your marketing plan to sell ahead of the curve before conditions dictate what you should do? Which animals in your herd are identified to be sold to reduce forage demand?

“If you’re a cow-calf producer, you can be pretty limited in flexibility, as selling the genetics of your cow herd that match their environment is difficult,” Derner said.

Having to buy hay and feed is also expensive, he said.

Ditto that, said Vaughn Isaacson, leader of a family farm and ranch in southern Saline County, but shifting the routine may take some time.

Sign up for HPJ Insights

Our weekly newsletter delivers the latest news straight to your inbox including breaking news, our exclusive columns and much more.

“In the cattle deal, you don’t just jump in and out.” he said. “These cow guys have got years of breeding some of these cattle.”

The livestock shift has been ongoing for several years near Hereford, Texas, where Chris Grotegut, a veterinarian, works on his family’s 11,000-acre farm and ranch. Critters include both sheep and cattle.

“Sheep will eat the weeds before the grass, and cattle eat the grass first,” he said. “We do not spray anything. We use livestock and we mow. We graze anything green.”

While there isn’t necessarily a rush to make wholesale changes in the livestock business, producers have noticed the extremes, and are aware of the past in these parts.

North of Gypsum in southeastern Saline County, Kansas, farmer Justin Knopf keeps eyes and ears trained on the “long game” despite cyclical setbacks.

“That’s what will enable me to survive when we have short-term extremes,” he said.

Among the questions that gnaw at him is, “How resilient is the cropping system we are building? In my mind, it starts with the soil, whether we have extreme rainfall or floods, or the other extreme, prolonged drought and heat.”

Sunlight and moisture are the other necessities.

“Soil and plants are the medium where all of that takes place,” Knopf said. “In order to weather extreme periods, I need a soil that is functioning well. By that, it has to be able to infiltrate and capture water and store it, and somehow have it available to the plants when they need it during dry periods.”

These days there seems to be more extremes, such as prolonged dry conditions.

Avoiding severe wind erosion during these times is important to Knopf, by keeping land covered with residue, “minimizing disturbance and holding on to what little moisture we receive by implementing conservation and soil health practices and keeping a living root in it as much as possible.”

Next on his list is adding diversity to his cropping system. Increasing the utilization of cover crops is a way he’s currently adding diversity and more living roots.

Knopf also believes perennials are another way to boost resilience. He’s been intrigued by several peers who are inserting a perennial grazing break for 5 plus years into their cropland, utilizing species similar to native prairies.

“Perennial grains would also add resiliency and bring additional benefits, but it’s a big ask to make a perennial plant produce grain amounts anywhere similar to an annual. I see potential to having a mixed grain and grazing system.”

His immediate concern is getting through this drought.

“Farmers long have paid attention to and adapted the best they can to the weather,” Knopf said. “If we’re going to have wetter wet periods and drier dry periods—more extremes, we’re going to have to think critically and be open to change.”

Tim Unruh can be reached at [email protected].